Along the shores of Africa’s Lake Victoria in Kenya roughly 2.9 million years ago, early human ancestors used some of the oldest stone tools ever found to butcher hippos and pound plant material, according to new research published in Science.

The study presents what are likely to be the oldest examples of a hugely important stone-age innovation known to scientists as the Oldowan toolkit, as well as the oldest evidence of hominins consuming very large animals.

, from Griffith University’s , was part of a large team of researchers led by scientists with the Smithsonian’s ³Ô¹ÏÍøÕ¾ Museum of Natural History and Queens College, City University of New York, as well as the ³Ô¹ÏÍøÕ¾ Museums of Kenya, Liverpool John Moores University and the Cleveland Museum of Natural History.

Associate Professor Louys was involved in the field work at the site, including the initial excavations collecting field data such as geospatial information and geological data.

Though multiple lines of evidence suggested the artifacts were likely to be about 2.9 million years old, the artifacts could be more conservatively dated to between 2.6 and 3 million years old, said lead author Thomas Plummer of Queens College, research associate in the scientific team of the Smithsonian’s Human Origins Program.

Through analysis of the wear patterns on the stone tools and animal bones discovered at Nyayanga, Kenya, the team behind this latest discovery shows that these stone tools were used by early human ancestors to process a wide range of materials and foods, including plants, meat and even bone marrow.

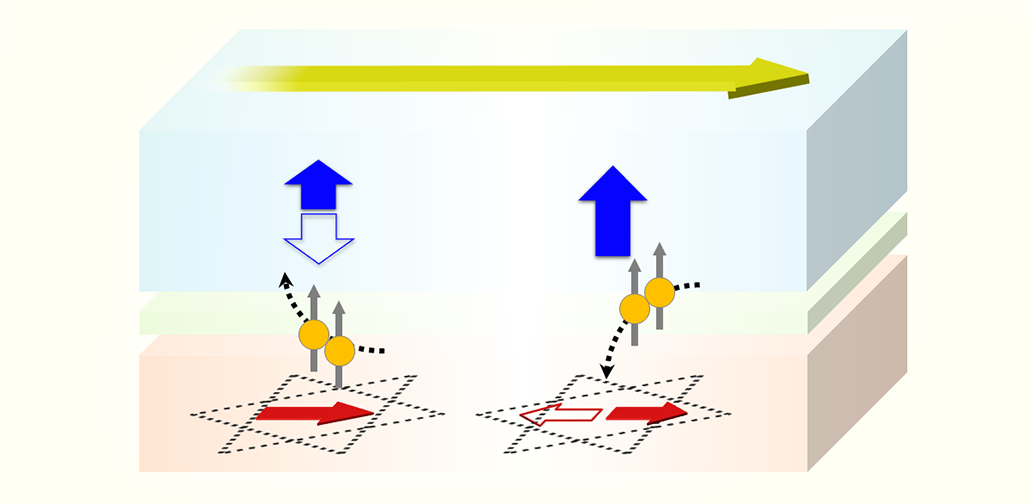

The Oldowan toolkit includes three types of stone tools: hammerstones, cores and flakes. Hammerstones can be used for hitting other rocks to create tools or for pounding other materials. Cores typically have an angular or oval shape, and when struck at an angle with a hammerstone, the core splits off a piece, or flake, that can be used as a cutting or scraping edge or further refined using a hammerstone.

“With these tools you can crush better than an elephant’s molar can and cut better than a lion’s canine can,” Potts said. “Oldowan technology was like suddenly evolving a brand-new set of teeth outside your body, and it opened up a new variety of foods on the African savannah to our ancestors.”

The site featured at least three individual hippos. Two of these incomplete skeletons included bones that showed signs of butchery. The team found a deep cut mark on one hippo’s rib fragment and a series of four short, parallel cuts on the shin bone of another.

Antelope bones at the site also showed evidence of hominins slicing away flesh with stone flakes or of having been crushed by hammerstones to extract marrow.

“What’s really interesting is that here at this site you have some of the earliest evidence of butchery of megafauna, even before the advent of the use of fire,” said Associate Professor Julien Louys.

“This indicates that exploitation of megafauna began millions of years before the so-called megafauna extinction event.”

The analysis of wear patterns on 30 of the stone tools found at the site showed that they had been used to cut, scrape and pound both animals and plants.

Because fire would not be harnessed by hominins for another 2 million years or so, these stone toolmakers would have eaten everything raw, perhaps pounding the meat into something like a ‘hippo tartare’ to make it easier to chew.

Using a combination of dating techniques, including the rate of decay of radioactive elements, reversals of Earth’s magnetic field and the presence of certain fossil animals whose timing in the fossil record is well established, the research team was able to date the items recovered from Nyayanga to between 2.58 and 3 million years old.

Excavations at the site, named Nyayanga and located on the Homa Peninsula in western Kenya, also produced a pair of massive molars belonging to the human species’ close evolutionary relative Paranthropus.

The teeth are the oldest fossilised Paranthropus remains yet found, and their presence at a site loaded with stone tools raises intriguing questions about which human ancestor made those tools, said Rick Potts, senior author of the study and the ³Ô¹ÏÍøÕ¾ Museum of Natural History’s Peter Buck Chair of Human Origins.

“The assumption among researchers has long been that only the genus Homo, to which humans belong, was capable of making stone tools,” Potts said. “But finding Paranthropus alongside these stone tools opens up a fascinating whodunnit.”

This research was supported by funding from the Smithsonian, the Leakey Foundation, the ³Ô¹ÏÍøÕ¾ Science Foundation, the Wenner-Gren Foundation, the City University of New York, the Donner Foundation and the Peter Buck Fund for Human Origins Research.

has been published in Science.