Researchers from UNSW Sydney’s have developed an enhanced version of a popular test for theory of mind, making it shorter and more effective for use with older adults.

The research, published in the , was led by CHeBA’s .

Theory of mind, sometimes known as “mindreading”, is the social skill of being able to tell what someone is thinking or feeling without that person explicitly stating their thoughts. This is commonly done through reading social cues and people’s expressions.

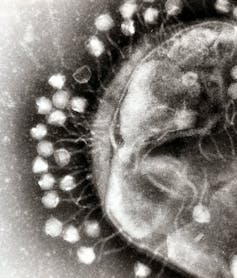

People’s expressions can be monitored just through the eyes which can be more expressive than most people think.

“People’s expressions can be monitored just through the eyes which can be more expressive than most people think,” said Russell Chander, a PhD candidate with CHeBA and lead author of the paper detailing the new assessment.

Currently, the most common assessment for theory of mind is the Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test; a 36-item assessment created by researchers from the Autism Research Centre at the University of Cambridge. This original assessment was first developed to assess theory of mind in young adults with autism spectrum disorders.

“Although it is an effective assessment to use in research studies such as with , it is not a test specifically designed for older adults,” said Mr Chander.

“The 36 items take some time to administer, and some older participants complained about its length,” he said.

Under the supervision of CHeBA’s Co-Director, Scientia Professor Perminder Sachdev, Mr Chander and the Social Cognition Ageing study team assessed data collected from 295 participants in the Sydney Memory and Ageing Study, with a mean age of 86 years, to shorten the Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test to a recommended 21 items. The data allowed them to identify the items in the original test most effective at measuring theory of mind performance, as well as determine which items could be removed without greatly affecting effectiveness of the test.

Mr Chander says that this data-driven approach allowed the numbers to speak for themselves.

“This ensured we would not unconsciously let our biases affect which items we chose,” explained Mr Chander.

The study team hopes that by making the test easier on older adults, it will help encourage more researchers and clinicians to use it with their patients and participants. They also hope to use this assessment in future CHeBA studies, to help improve participants’ experiences with research.

“Social cognition has not received the attention it deserves. It appears to change with ageing and especially in the early stages of dementia. We need the right tools to measure it in older people, and this adaptation of the Reading the Mind in the Eyes is one step toward this objective,” added Professor Sachdev.

Theory of mind, along with other social skills and abilities – collectively known as social cognition – appears to be affected in some older adults. Poor social cognition may affect one’s ability to function well in social settings and may also be an early warning sign of dementia. More work is still needed to fully understand how social cognition functions in ageing and dementia, and the social cognition researchers at CHeBA are continuing to add to this knowledge.

This study is being performed in collaboration with Prof Julie Henry of the University of Queensland and is funded through an Australian Research Council grant.

Russell Chander is supported by the UNSW Scientia PhD program.