The of the Academy’s journal, Historical Records of Australian Science, is devoted to the history of plant pathology in Australia. Despite the challenges of academic isolation and lack of communication, early plant pathologists flourished and made many world-first discoveries that assisted Australian farmers to overcome challenges in crop growth.

This special issue, published in cooperation with the Australasian Plant Pathology Society, pays specific attention to describing some of the major plant diseases that affected agriculture during the 19th and early 20th centuries.

According to Associate Professor Andrew Geering of the University of Queensland, the guest editor of this issue, Australia is one of the most food secure nations in the world with farmers producing enough to feed three times the country’s population.

However, farmers have had to overcome many challenges to grow their crops, including extreme weather variability, shallow and infertile soils, and attacks by pests and pathogens. Early attempts to transplant European farming practices into Australia often failed, and extensive scientific research was required to achieve the current level of success.

Boom-and-bust environment

Little is known about the impact of plant pathogens on Indigenous food systems prior to colonisation and whether there was active intervention by Indigenous Peoples to prevent or treat plant diseases other than by fire management. However, it’s likely that the impacts of plant diseases would have been much less severe than now, as the Indigenous Peoples had learnt to cope with the boom-and-bust nature of the Australian environment.

Indigenous family units were not anchored to a single plot of land, and local declines of a plant species due to disease would not have posed the same threat to food security because of the mobility of these peoples. Indigenous communities also utilised a much more genetically diverse food base, both at the individual plant species and plant community levels.

One of the major causes of plant disease epidemics in modern cropping systems is the planting of large areas of genetically uniform plant varieties that are a susceptible to one or more plant pathogens. It did not take long after the British colonisation of Australia for plant diseases to make an impact, with crop failure from stem rust and smut disease of wheat occurring in the convict settlement of Sydney in the first few years of the 1800s. Wheat was the staple starch crop, and the arrival of these two diseases would have been hardest felt by the very poorest in society, who lived mainly on bread and cheese, supplemented by butter and meat if they could afford them.

The first plant pathologist

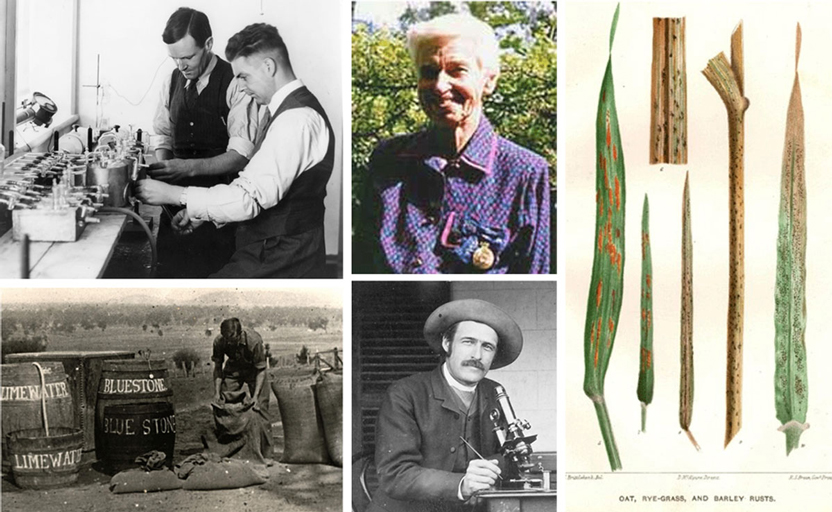

Continuing epidemics of wheat stem rust throughout the 19th century prompted the appointment of the first plant pathologist in Australia, Daniel McAlpine, who in May 1890, was made Consulting Vegetable Pathologist to the Department of Agriculture in Victoria (the term ‘Vegetable’ was used in the traditional sense, to refer to all edible plant matter). It is thought that this was the very first full-time appointment of its kind in the British empire. The Government of New South Wales was quick to follow, appointing Nathan Cobb as its plant pathologist. The other colonies (later states) took longer to act, and McAlpine and Cobb served the plant pathology needs of much of Australia for at least a decade.

There was no scientific specialisation among the early plant pathologists-they were equally adept at researching plant pathogenic bacteria as fungi, swapping between the subject areas with ease. Joseph Bancroft was a medical surgeon when he discovered Fusarium wilt of banana, and even joined the royal commission to investigate the rabbit problem!

Pathologists had to work in isolation, not aware of what was happening in the neighbouring jurisdictions, let alone overseas. The discoveries they made are even more remarkable because of this fact. In addition, there was slow recognition of the discoveries made in Australia within the scientific powerhouse nations of North America and Europe. Rupert Best deserved to be a joint Nobel Prize winner with Wendell Stanley for the physico-chemical characterisation of tobacco mosaic virus. However, as lamented by Best himself, the chances of an Australian scientist based in Australia winning a Nobel Prize prior to World War II were virtually nil.

Prejudice and rivalry

Along with successes, the early plant pathologists and the organisational structures within which they worked had many flaws, including a gender bias towards men. , one of the pioneering female plant pathologists of Australia, suffered much prejudice and misogyny. Racial prejudice was also widespread in the 19th and early 20 centuries, some of it officially sanctioned by the Australian Government through the ‘White Australia policy’. Australians of Chinese and South Pacific Islander heritage were victims of this racial prejudice in the banana and sugarcane industries, respectively. Finally, many of the early male plant pathologists were very egotistical, and interstate rivalry was rife even a few decades after the federation of Australia. There was much unnecessary bickering that impeded the progress of research, and the contributions of farmers to solving plant disease problems were also ignored or not properly recognised by the scientists.

This content above is adapted from the by Associate Professor Geering, who is President of the Australasian Plant Pathology Society and Vice President-elect of the International Society for Plant Pathology. The full article contains references. The response by authors in this topic was so great that the next issue of Historical Records of Australian Science, due in January 2025, will contain more fascinating research on the history of plant pathology in Australia.

All 16 articles in this special issue are open access.