Air pollution is a growing health issue worldwide, and its impacts are often underestimated in aging societies like Japan. A new study led by researchers from the University of Tokyo highlights how fine particulate pollution, or PM2.5, not only worsens health outcomes, but also creates significant socioeconomic challenges in regions with aging populations and limited medical resources. The researchers hope these findings motivate policymakers to tackle the interrelated issues behind this problem.

PM2.5 refers to microscopic particles of pollution small enough to penetrate deep into the lungs and bloodstream, leading to severe respiratory and cardiovascular diseases. PM2.5 are small enough to evade the body’s natural defenses in the nose and throat, making direct prevention difficult. This becomes especially problematic in elderly populations.

“As we age, our immune systems weaken and our bodies are less able to defend against pollutants. Even moderate exposure can exacerbate pre-existing conditions, leading to higher hospitalization rates and premature mortality,” said lead author Associate Professor Yin Long. “Our study provides new insights into impacts of PM2.5 in aging regions, with a particular focus on the mismatch between those impacts and regional medical resource distribution.”

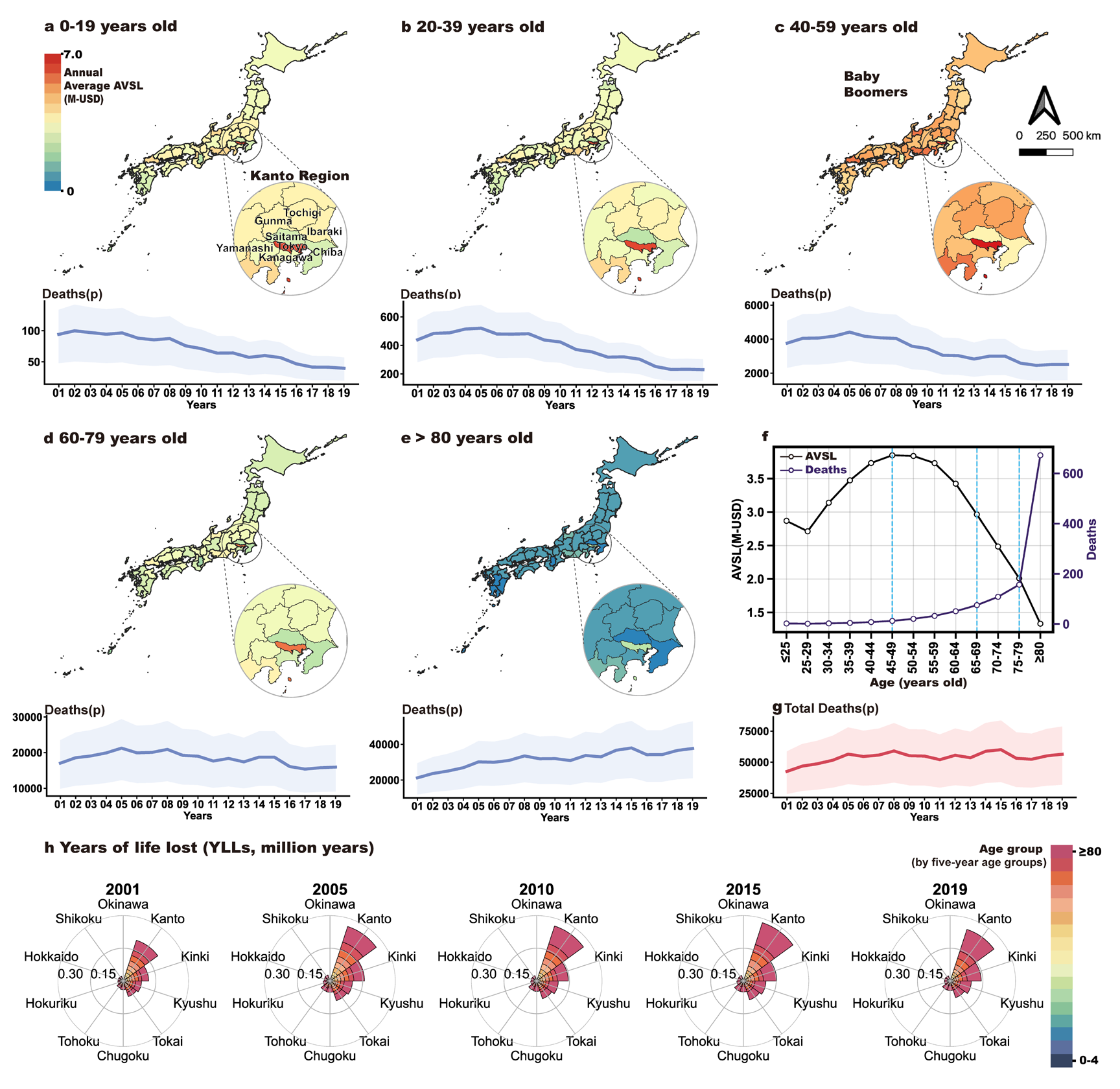

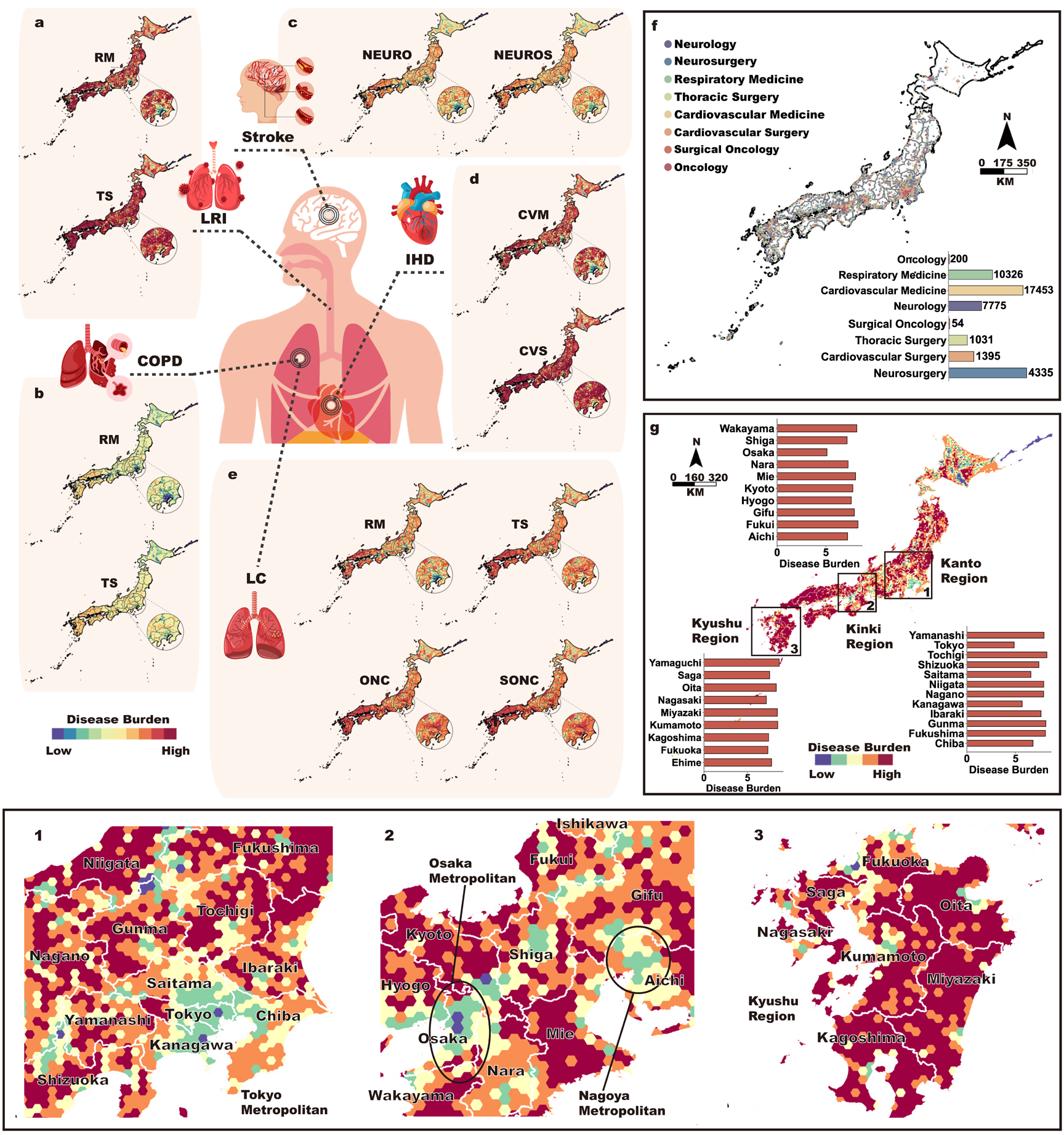

The study focuses on Japan, a country where almost 30% of the population is aged 65 or older. Researchers examined the relationship between PM2.5 exposure, health care disparities and economic impacts. They found that rural regions in western Japan, where aging is more pronounced, suffer disproportionately from the dual burden of PM2.5 pollution and less comprehensive medical infrastructure. These areas face higher economic costs compared to urban regions, which tend to be much better equipped and staffed.

“Many rural areas lack the specialized hospitals and trained professionals needed to treat diseases exacerbated by PM2.5, such as strokes and heart attacks,” said Long. “For some working-age seniors, PM2.5 exposure is linked to increased rates of severe illnesses, forcing many to leave the workforce earlier than planned. This not only affects their financial independence, but also places additional pressure on younger generations to support them.”

The study’s economic analysis reveals PM2.5-related deaths and illnesses contribute to rising socioeconomic costs that exceed 2% of the gross domestic product in some regions. The intergenerational inequality PM2.5 impacts poses a challenge for policymakers aiming to ensure both economic stability and equitable access to health care. The researchers emphasize these issues are not limited to Japan. Countries with aging populations and rising pollution levels, including China and parts of Europe, might face similar challenges.

“Our framework can be adapted to analyze these impacts globally. By identifying the most vulnerable populations and regions, governments can allocate resources more effectively,” said Long. “For example, stricter pollution controls, investments in health care infrastructure and international cooperation to address transboundary pollution could all help. And expanding green infrastructure in urban areas can increase plants which naturally filter pollutants, while telemedicine could improve health care access in remote regions.”

Long and her team also suggest policies targeting vulnerable populations, such as subsidies for elderly care and community health programs. “The health of our elderly is not just a personal matter, it’s a public issue with profound social and economic implications,” said Long. “Acting now could save lives and reduce long-term costs for everyone.”