New models of care and more investment are urgently needed to reach people at risk or living with hepatitis C, and engage people lost to care, otherwise Australia risks falling short of its goal to eliminate hepatitis C as a public health threat by 2030.

Key findings of the Burnet Institute and Kirby Institute’s released today, show:

- the rate of new hepatitis C infections in Australia has declined since 2016 when highly effective direct acting antiviral (DAA) treatments became available, and

- more than 95,000 people were treated with DAAs between 2016 and 2021.

However, the report also reveals declines in testing and in the number of people treated each year.

This leaves an estimated 117,800 Australians still living with hepatitis C at the end of 2020 and at serious risk of liver disease, cancer, and premature death.

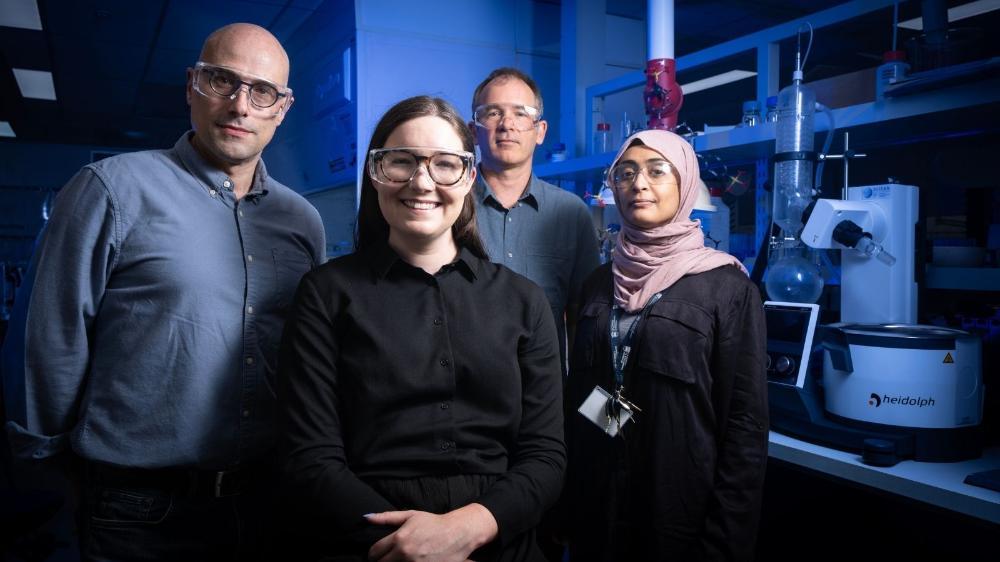

Report co-author and Burnet Institute Head of Public Health, Professor Mark Stoové warns Australia risks squandering the golden opportunity provided by the DAAs and a first-class health system.

“We’ve got a great foundation in the successes that we’ve had over the last five years, but the approaches that underpinned that foundation are no longer sufficient to achieve elimination,” Professor Stoové said.

“We need to innovate our models of care and work hard to make sure we reach the remaining Australians living with hepatitis C that are yet to be treated.”

Models of care should better integrate hepatitis C care into alcohol and other drug treatment services, including opioid agonist therapy and NSPs (needle and syringe programs), and adapting primary care services to make sure they reach people with or at risk of hepatitis C.

The recent approval of point-of-care testing for hepatitis C also creates new opportunities for diagnosis and treatment.

“We’ve made DAAs readily accessible so any general practitioner or nurse practitioner or clinician in a community or prison health care service can prescribe them,” said Professor Gregory Dore, Head of the Viral Hepatitis Clinical Research Program at the Kirby Institute, UNSW Sydney.

“But it’s not good enough to just make the drugs available through these settings.

“When a person at risk of hepatitis C presents to a service, we need to make the most of those engagement points, ask whether they’ve been tested in the past or tested recently and offer testing and treatment within that same model of care.

“The national initiative to implement point-of-care hepatitis C testing in community and prison settings should provide impetus to enhanced screening and rapid linkage to treatment, key requirements to re-invigorate the hepatitis C elimination efforts.”

Maximising the use of current surveillance systems can also help to find people previously diagnosed who have been lost to care.

“There’s a lot of goodwill in the sector in terms of how we can work together more smartly in the delivery of services, but we need to invest in new models of care that can accelerate our progress towards elimination,” Professor Stoové said.

“That’s going to be a challenge over coming years, but it’s critical that we don’t squander the opportunity that’s been provided by the DAAs.”

Transmitted by blood containing hepatitis C, often from shared needles or injecting equipment, hepatitis C attacks the liver and leads to inflammation.

Most people have no symptoms, and if left untreated hepatitis C can lead to cirrhosis, liver failure or liver cancer.

for the Report and other resources