For almost a decade, Indigenous Studies scholar Professor Bronwyn Carlson has researched the ways Indigenous people use social media to build community and identity, while also facing persistent online violence in these spaces.

Author Professor Bronwyn Carlson, Lecturer in the Department of Indigenous Studies Madi Day, and Professor Grace L. Dillon, Anishinaabe, Portland State University.

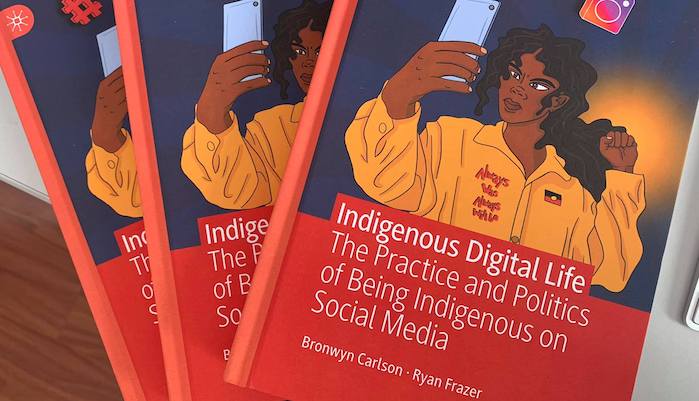

Carlson – herself an Aboriginal woman – details the findings of her extensive research on Indigenous people’s engagements on social media since 2013, in a new book with Ryan Frazer, Indigenous Digital Life: The Practice and Politics of Being Indigenous on Social Media.

Indigenous people’s use of Facebook is around 20 per cent higher than the national average across all geographical locations.

“There is also a growing community of Indigenous voices on Twitter and a significant number of TikTok users,” she says.

I’m interested in the way that Indigenous people participate in digital life, including love and joy and humour and community, despite the online violence they have to deal with.

Her research shows that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people use platforms like Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, TikTok and others to communicate and network with friends and family, share stories and knowledge about various cultural practices, seeking and offering help and rally against racism and discrimination.

“Social media is an intrinsic part of daily life, with many people spending in excess of five hours a day online,” she says, adding that social media is a rich space to explore many different aspects of people’s lives.

Shining a light on digital community

Carlson says that while online violence is an ever-present facet of her research, it’s only part of the picture.

“I’m interested in the way that Indigenous people participate in digital life, including love and joy and humour and community, despite the online violence they have to deal with,” she says.

“Rather than only focussing on negative and often violent interactions that Indigenous people face online, I wanted to write about our whole humanity, how we connect with each other, our humour, our creativity and our powerful stories of love and survival and family.”

One powerful example emerged in response to a racist cartoon about Indigenous fathers by the late Bill Leak following horrific revelations of abuse of Indigenous children by employees in the Don Dale juvenile detention centre.

These campaigns use creative social media strategies to resist, subvert and challenge the political status quo.

“Aboriginal man Joel Bayliss tweeted an image of himself and his children stating ‘To counter the Bill Leak cartoon, here is a pic of me & my kids. I am a proud Aboriginal father’,” she says.

“Indigenous people went online using the hashtag #IndigenousDads and flooded Twitter with beautiful pictures of their dads, their uncles, their families, showing men with their children playing sport and music and fishing, and lovely images of everyday family life.”

Other examples include the #SOSBlakAustralia hashtag, which sought to stop the forced closure of Aboriginal communities in Western Australia, and the #BlackLivesMatter movement which has raised awareness of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander deaths in custody and police brutality.

“These campaigns use creative social media strategies to resist, subvert and challenge the political status quo,” Carlson explains.

Face of community connection

Carlson says that the culture of strong links between generations common in Indigenous communities is often reflected on social media platforms, which play a crucial role in the lives of many Indigenous people, helping facilitate vital networks of support, care and knowledge.

Powerful stories: The image of Joel Bayliss, tweeted by Bayliss “to counter the Bill Leak cartoon … I am a proud Aboriginal father”, prompting the #aboriginalDads campaign.

“My research shows social media is used differently by Indigenous people. While young people in other cultures often dismiss Facebook as a place where their parents gather, we found that younger Indigenous people use it to connect to older relatives,” she says.

Facebook has served as an avenue to reconnect for people displaced from their families by past government policies and practices, she says – a process likely to continue to be important, as there are currently care.

But while these platforms serve a positive community purpose, Carlson adds that users feel a strong sense that social media isn’t a neutral or private space in which drama, conflict, and arguments might take place; an Indigenous person’s online behaviours can have broader cultural, social, and political ramifications.

“Indigenous people are bound by cultural protocols and norms and are not necessarily free to post without consideration for the collective,” she says. “This is particularly the case for issues related to Sorry Business.”

Indigenous people’s use of dating apps

Her yearning to write about the lighter side of digital community brought Carlson to her recent landmark study in the prestigious international Journal of Sociology, titled ‘Love and Hate at the Cultural Interface: Indigenous Australians and dating apps,’ exploring the ways that Indigenous people engaged with apps such as Tinder and Grindr.

‘Love and hate’: Carlson found heterosexual women on Tindr experienced racism and misogyny, but “this doesn’t tell the whole story”.

She found gay Indigenous men on Grindr often experienced racism and homophobia – and that sexual preferences on Grindr were more strongly influenced by political factors, than by phenotypic preferences.

Similarly, Carlson found heterosexual Indigenous women on the dating app Tinder experienced racism and misogyny.

“This doesn’t tell the whole story though,” Carlson says – and her new book explores the experiences of Indigenous people using social media and dating apps to seek romantic love and fulfil sexual desires.

“There were moments that were fun and comical, such as when people justified their ‘sugar daddy’ relationships through references to Indigenous ‘reparations’, or when others who lived in tight-knit communities struggled to find ‘dates’ with someone who was Indigenous yet not related,” she said.

The Dark Side: the historic origins of hate

Her research into social media spaces has consistently found extensive incidence of online violence, and Carlson says that more recently she has broadened her focus to look at the social and structural determinants of these acts.

Madi Day and Gadigal drag performer, Nana Miss Koori.

“I realised that I had previously focused on the impact of this violence on us and the strategies we use to deal with it, as opposed to looking at the perpetrators and trying to understand: what is it that makes someone behave in such a hateful, horrible way?”

Carlson’s research with Madi Day explores how Indigenous people using social media are affected by existing Indigenous-settler power relations, stereotypes and ‘regimes of surveillance’.

They have co-authored a chapter, ‘Predators & Perpetrators: White settler violence online’ to published .

“Much of today’s online violence can be tracked back to an ongoing history found in settler diaries and accounts of Aboriginal women, in which male colonists brag about their sexual violence and violence against women,” Carlson says.

“Racist stereotypes of Indigenous people work to sustain and legitimise a settler colonial state based on the founding ‘terra nullius’ myth positing this continent now known as Australia as a land without people, free for British forces to appropriate,” she says.

“Since then, harmful colonial policies have been enacted across two centuries, based on racist representations of Indigenous people as, variously, lazy, alcoholics, neglectful parents, and criminals,” she says.

Writing your own identity

Even apparently sympathetic portrayals of Indigenous people by government and media sources too often represent a “narrative of negativity, deficiency and disempowerment” that defines Indigenous people by their supposed shortcomings, she says.

“This kind of narrative perpetuates stereotypes of Indigenous people and reinforces prejudice,” says Carlson.

Social media – by contrast – has given users the power to represent themselves, to speak back to stereotypes and call out unacceptable racist and violent behaviour.

“I’m fascinated by the way in which we speak back to those things – digital representation is not a substitute for real life, it’s a reflection of it – so we can learn a lot by exploring the way that these expressions of community, connection and love and hate continue within these digital spaces.”

is a Professor in the Department of Indigenous Studies