In , NC State researchers looked at 18 dogs infected with a strain of the bacteria Bartonella called Bartonella rochalimae. They documented the health effects of the bacteria, which included infectious endocarditis – an inflammation of the heart’s inner lining and valves – as well as more general chronic illness. The work is further evidence of the connection between B. rochalimae and both endocarditis and chronic health effects in dogs and may have implications for human health. Lead author Ed Breitschwerdt, Melanie S. Steele Distinguished Professor of Internal Medicine and Bartonella expert, sat down with The Abstract to answer some questions about the new findings.

The Abstract (TA): It looks as though the dogs in the study show evidence that this particular strain is associated not just with infectious endocarditis (IE), but also with the persistent health problems we see with infections from more common Bartonella (B. henselae, etc) species?

Breitschwerdt: That is correct. The association with endocarditis was very recent as well. So this manuscript provides further support for this species as a pathogen in dogs and humans.

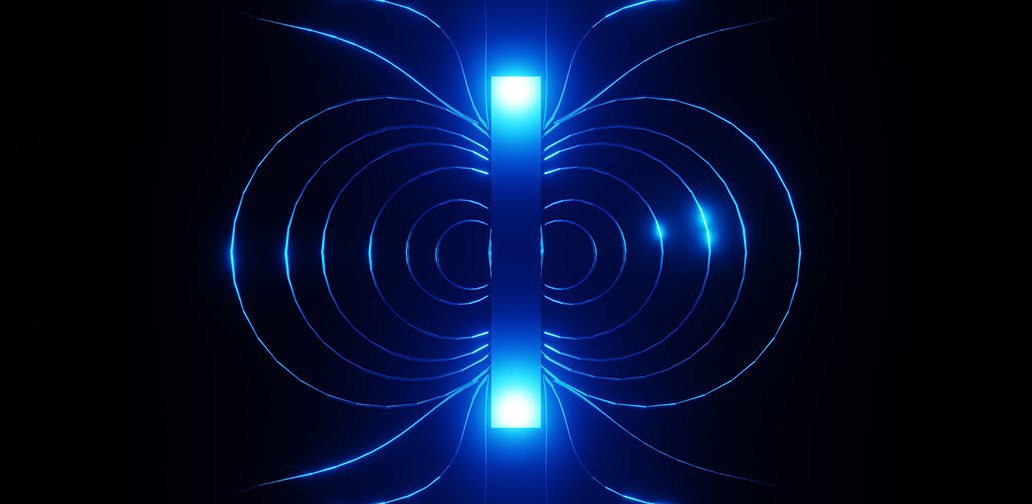

Bartonella is now a well-recognized cause of what was historically culture-negative endocarditis; that is, patients (dogs and humans) with echocardiographic evidence of endocarditis and no bacterial growth using conventional blood cultures.

TA: How many strains of Bartonella have been identified to date? How is B. rochalimae different from other strains of Bartonella? Do different types of fleas or insect vectors carry particular strains, is it geography-based, or is it just luck of the draw?

Breitschwerdt: We are currently at around 40 named Bartonella species or subspecies, 10 of which have caused IE in a dog or human. Unfortunately, we have very little information in veterinary or human medicine regarding potential differences in how we should be most effectively diagnosing and treating specific Bartonella species or subspecies. Thus, most diagnostic and treatment considerations are based upon experiences with the most common Bartonella species (Bartonella henselae) that infect dogs and humans.

The genus Bartonella is unique among vector borne pathogens in the context of the wide spectrum of arthropod vectors that are known or suspected to transmit these bacteria. Yes, there are definitive geographical localizations, such as Bartonella bacilliformis, transmitted by a specific sandfly species in the mountainous Andes in Peru and Ecuador.

Alternatively, Bartonella henselae is transmitted to cats by a specific flea species throughout much of the world. Rodents and small mammals are frequently infected with specific Bartonella species in specific geographic locations by an evolutionarily adapted flea species that tends to selectively infest specific hosts or a narrow host range.

Most recently bats, infected by bat flies, have become another important reservoir for newly discovered Bartonella species. Importantly, a bat-associated Bartonella species (Candidatus Bartonella mayotenensis) was first identified as a cause of culture-negative endocarditis in a patient at the Mayo Clinic by amplification and sequencing of the bacterial DNA from the patient’s heart valve. It was several years later when bats were found to be reservoirs for this new species.

TA: Are there strains of Bartonella that aren’t associated with what we think of when we think of bartonellosis: the mimicking of chronic diseases like multiple sclerosis, migraines, seizures, etc?

Breitschwerdt: The diagnosis of infection with a Bartonella species remains challenging despite improvements in microbiological isolation and DNA detection methodologies. A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primer set used in our laboratory to detect other Bartonella species with a high degree of sensitivity did not find B. rochalimae DNA. This is only one of many examples of the need for more comprehensive (sensitive and specific) diagnostic tests that will clarify the role of Bartonella species in patients with migraines and seizures. We continue to work on improvements in diagnostic testing modalities, while attempting to clarify the role of Bartonella species in a spectrum of chronic diseases.

TA: Does this particular strain really “like” the aortic valve, or is that true of Bartonella generally?

Breitschwerdt: In both dogs and humans, approximately 75% of Bartonella IE cases involve the aortic valve. The remaining 20-25% involve the mitral valve or both the mitral and aortic valves. Thus it is clear that all Bartonella species to date have a predilection to localize to the aortic valve.

TA: How prevalent is IE in dogs? Is it always fatal?

Breitschwerdt: IE is a relatively uncommon disease. Depending upon the study, Bartonella can be the cause of over 1/3 of IE cases in dogs, which is remarkable as we did not know this genus infected dogs until 1993, when the first case of IE bartonellosis was documented at NC State’s College of Veterinary Medicine. That is the first case of bartonellosis in a dog worldwide.

TA: Is this something that veterinarians should be taking into consideration when treating dogs with infectious endocarditis? Would it change the treatment regimen in terms of type or dosage of antibiotics?

Breitschwerdt: Yes, there are special antibiotic selection considerations when Bartonella is the suspected or confirmed cause of endocarditis. Not a good infection to have or an easy infection to treat.

- Categories:

- Tags: