Clothing is understood as a significant component in shaping what makes us human. The emergence of clothing enabled our ancestors to inhabit more corners of the world, access different resources and environments, and connect with a broader community. Today, clothing is associated with identity and status. Yet archaeological evidence indicates that apart from thermal reasons, clothing was not intrinsic for society or cultures to function.

.jpeg/_jcr_content/renditions/cq5dam.web.1280.1280.jpeg)

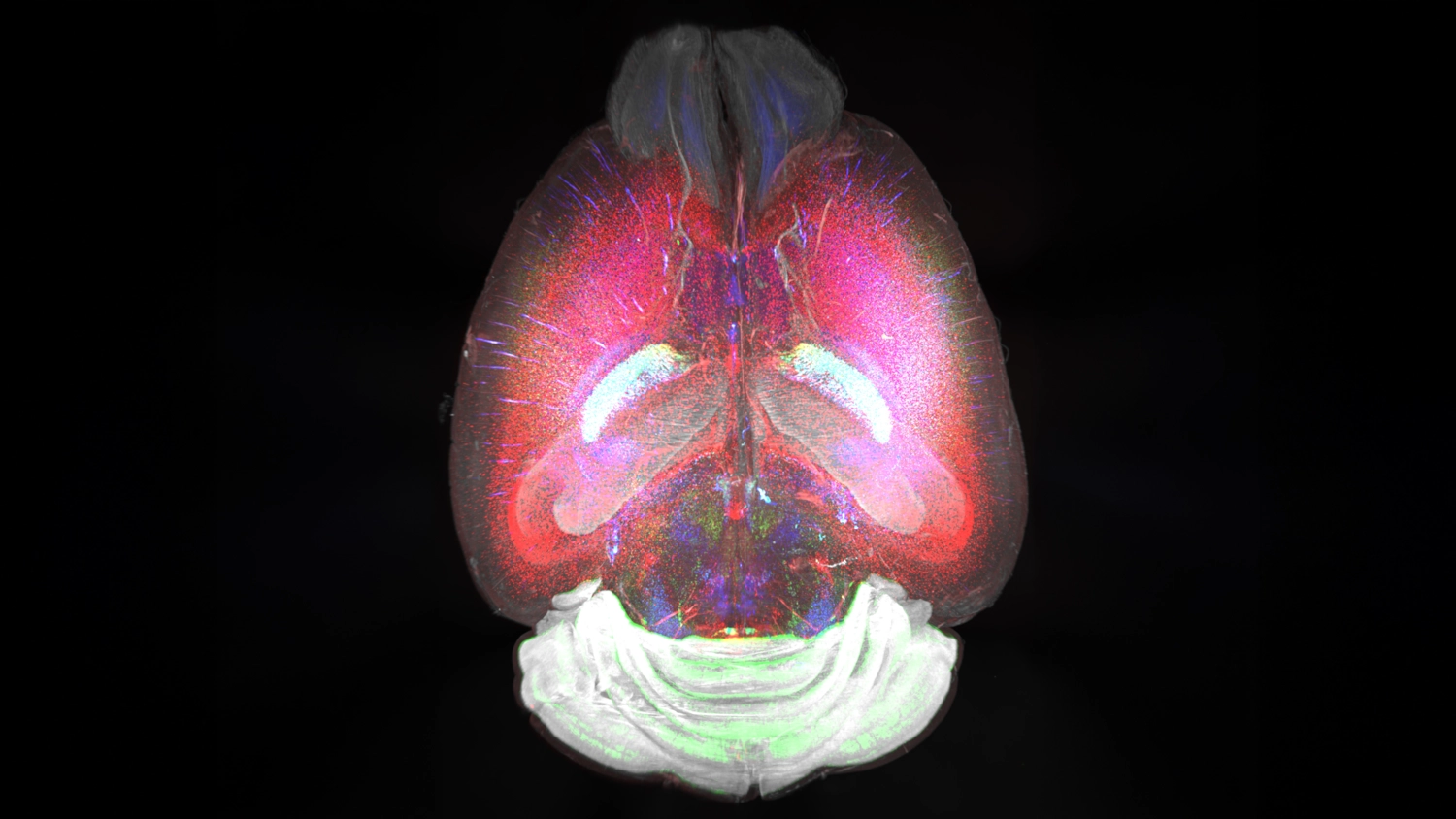

Artist impression of decorated tailored clothing in the Upper Paleolithic. Image credit: Mariana Ariza.

A team of researchers led by Dr Ian Gilligan, Honorary Associate in the discipline of Archaeology at the University of Sydney, are the first to suggest that eyed needles were a new technological innovation used to adorn clothing for social and cultural purposes, marking the major shift from clothes as protection to clothes as an expression of identity.

“Eyed needle tools are an important development in prehistory because they document a transition in the function of clothing from utilitarian to social purposes,” says Dr Ian Gilligan.

Dr Gilligan and his co-authors reinterpret the evidence of recent discoveries in the development of clothing in their paper, .

“Why do we wear clothes? We assume that it’s part of being human, but once you look at different cultures, you realise that people existed and functioned perfectly adequately in society without clothes,” Dr Gilligan says. “What intrigues me is the transition of clothing from being a physical necessity in certain environments, to a social necessity in all environments.”

The earliest known eyed needles appeared approximately 40,000 years ago in Siberia. One of the most iconic of Paleolithic artefacts from the Stone Age, eyed needles are more difficult to make when compared to bone awls, which sufficed for creating fitted clothing. Bone awls are tools made of animal bones that are sharpened to a point. Eyed needles are modified bone awls, with a perforated hole (eye) to facilitate the sewing of sinew or thread.

As evidence suggests bone awls were already being used to create tailored clothes, the innovation of eyed needles may reflect the production of more complex, layered clothing, as well as the adornment of clothes by attaching beads and other small decorative items onto garments.

“We know that clothing up until the last glacial cycle was only used on an ad hoc basis. The classic tools that we associate with that are hide scrapers or stone scrapers, and we find them appearing and going away during the different phases of the last ice ages,” Dr Gilligan explains

Dr Gilligan and his co-authors argue that clothing became an item of decoration because traditional body decoration methods, like body painting with ochre or deliberate scarification, weren’t possible during the latter part of the last ice age in colder parts of Eurasia, as people were needing to wear clothes all the time to survive.

.jpg/_jcr_content/renditions/cq5dam.web.1280.1280.jpeg)

Morphological variation in the size and shape of Late Pleistocene eyed needles. Scale bar, 1 cm. Image credit: Gilligan et al, 2024.

“That’s why the appearance of eyed needles is particularly important because it signals the use of clothing as decoration,” Dr Gilligan says. “Eyed needles would have been especially useful for the very fine sewing that was required to decorate clothing.”

Clothing therefore evolved to serve not only a practical necessity for protection and comfort against external elements, but also a social, aesthetic function for individual and cultural identity.

The regular wearing of clothing allowed larger and more complex societies to form, as people could relocate to colder climates while also cooperating with their tribe or community based on shared clothing styles and symbols. The skills associated with the production of clothing contributed to a more sustainable lifestyle and enhanced the long-term survival and prosperity of human communities.

Covering the human body regardless of climate is a social practice that has endured. Dr Gilligan’s future work moves beyond the advent of clothing as dress and looks at the psychological functions and effects of wearing clothes.

“We take it for granted we feel comfortable wearing clothes and uncomfortable if we’re not wearing clothes in public. But how does wearing clothes impact the way we look at ourselves, the way we see ourselves as humans, and perhaps how we look at the environment around us?”

This paper was published in .

DECLARATION

The authors declare no competing interests. This research was supported by the following agencies: Initiative d’Excellence IdEx, University of Bordeaux; French government in the framework of the University of Bordeaux’s IdEx “Investments for the Future” program / GPR “Human Past”; Research Council of Norway, Centres of Excellence (SFF), Centre for Early Sapiens Behaviour; European Research Council Synergy Grant for the project Evolution of Cognitive Tools for Quantification (QUANTA); The ³Ô¹ÏÍøÕ¾ Social Science Foundation of China, The Taishan Scholars Project Special Funds, State Assignment of the Sobolev Institute of Geology and Mineralogy, Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

Hero image: Artist impression of decorated tailored clothing in the Upper Paleolithic, Mariana Ariza.