│į╣Ž═°šŠ modifications can help delay institutional care, creating benefits for the individual, the taxpayer and the healthcare system.

Professor Catherine Bridge (right) is determined to improve the accessibility of the built environment through inclusive design that attends to the needs of diversity. Former occupational therapist Penny Plumbe (left). Photo: Quentin Jones

A UNSW Built Environment professor is determined to improve the accessibility of the built environment, which could improve the outcomes for some of the most vulnerable populations – the elderly and the disabled.

Professor Catherine Bridge runs the Livability Design Lab at UNSW Built Environment, which pioneers inclusive design using cutting-edge technology such as motion capture and biomechanical analysis software to analyse the barriers to accessibility in the built environment.

She says that current assumptions about design are preventing the built environment from being inclusive.

“The idea of wellbeing is modelled on a healthy, middle-aged man, and so that is how it [the built environment] is designed,” she says.

“This is not representative of the population … especially those [the elderly and the disabled] who experience some form of functional impairment.”

According to Professor Bridge, the accessibility of the built environment is a factor of inclusion that is often overlooked.

Even designs that are accessible are typically not aesthetic, which prevents people from engaging with their environments, particularly in the home, she says.

“Historically, modifications such as handrails and ramps have been designed by modifying industrial equipment … or they’re things you would see in a hospital or in a public access bathroom, which are stigmatising because they scream ‘disability’.

“The goal should not be just to meet the minimum standards.”

Professor Bridge suggests the need to improve the inclusiveness of the built environment is at a tipping point as the demographic shifts towards an ageing population.

She believes a more proactive planning model based on inclusion would deliver better outcomes in all aspects.

“The ‘solution’ to a challenge such as population ageing is usually to build more hospitals or aged-care facilities.

“Instead, what we should be asking is: what else could we do that would prevent people from going to the hospital in the first place, or prevent people from going into an aged care facility, which will cost less and, in fact, have better economic and social outcomes?”

Professor Bridge believes the solution lies within the home by extending ageing in place.

What she hopes to see is individuals empowered to live in their homes for longer, which can reduce the need for care, while improving quality of life in every metric.

“Overwhelmingly, the research shows that people want to remain in their homes, rather than enter institutional care facilities,” she says.

“We know that [people staying in their homes] can reduce the need for care by 47%1 and lead to a 40% improvement in a person’s quality of life2.”

“If we can effectively delay [institutional care] by just five years through ageing in place, that is huge for not just the individual’s wellbeing, but also the taxpayer and the healthcare system.”

Professor Bridge is also the Director of the │į╣Ž═°šŠ Modification Information Clearinghouse (HMInfo), a unique information service which provides the evidence base for housing retrofit across Australia.

“People historically … have focused on only one aspect, either disability or sustainability, but no one looked at how they intersect.

“[HMinfo] is unique in that it bridges this gap between the wants, needs and desires of the older person or the person with the functional disability, and that of the industry – the built environment sector and the health sector.”

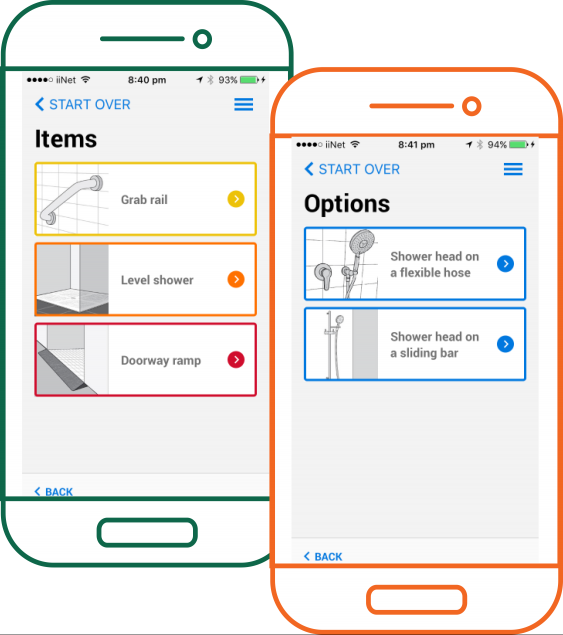

The information service combs through academic literature, industry best-practice principles and combines this with research from the Livability Design Lab to develop user-friendly materials, including factsheets and mobile applications, which have been used by more 200,000 people, from consumers to industry and policymakers.

HMInfo apps like DIYmodify provide information for making home modifications such as grab rails and handheld showers.

She says the unique service – HMInfo – provides practical support and empowers individuals to age in place for longer, enabling them to have greater autonomy and reduce the burden on the healthcare system.

“The fact sheets and checklists help people in a practical way when they are thinking about: should I put a ramp in? Or should I put in a lift? How do I get permission from a building owner to perform a modification?

“HMInfo fact sheets are updated at a moment’s notice when there is a change in legislation, and it also curates the latest home-modification products as soon as they hit the market.

“So it goes from quite theoretical to incredibly practical.

“There is no other service of its kind in terms of providing specific home modification information,” she says.

For Professor Bridge, it is about making a practical difference, by ensuring individuals are valued and supported throughout all stages of life.

“Ultimately, people just want to be valued and supported.

“If you are concerned with making society inclusive, the only way to do that is to change the built environment,” she says.

“My work, and all of the work that we do, is really about understanding that, and how we can improve that trajectory through life.”

- Bridge C;Carnemolla PK, 2017, ‘Effective │į╣Ž═°šŠ Modification Practice’, in Curtin M;Molineaux M (ed.), Occupational therapy for people experiencing illness, injury or impairment: Promoting occupation and participation, edn. 7th, Elsevier, pp. 690 – 705

- Carnemolla P, Bridge C. (2016). Accessible housing and health-related quality of life: measurements of wellbeing outcomes following home modifications. Archnet-IJAR [serial online]. July;10(2):38-51.