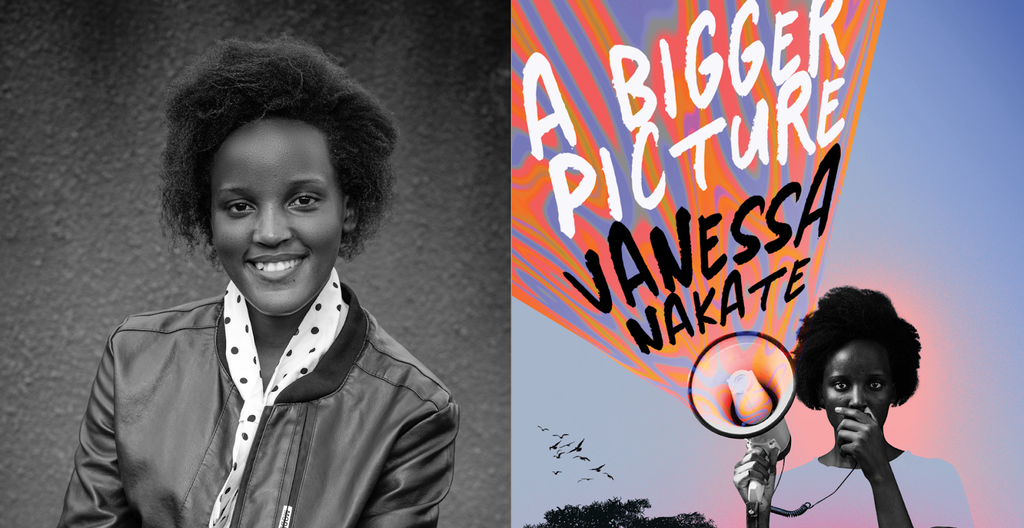

Ugandan climate activist Vanessa Nakate is fast becoming a formidable voice in the climate movement. She has shared with us an excerpt from her new book, A Bigger Picture: My Fight to Bring a New African Voice to the Climate Crisis, in which she discusses the impact African women and girls can have on solving the climate crisis once their access to education is ensured.

One morning, when I was only a few years old, I went missing from home. My parents looked high and low for me. Eventually, I was found sitting in a classroom at a nearby nursery school, ready to learn. The same thing happened the next day. My father asked the teacher what could be done, since I was too young to be enrolled in the school but I threw a tantrum if I was taken out of the class. The teacher replied that it was illegal for my father to pay to educate an underage child, but agreed that I could stay for free. So, every morning I attended the school, and I was eventually enrolled, a year earlier than I should have been.

I obviously had a hunger for learning, and I’m very fortunate my parents championed my education, particularly as a girl, and worked hard to ensure they had the money for school fees, even in some lean years. My mother stressed that there was no future for me if I didn’t study and acquire expertise and skills to be able to earn my own income. To her, and to me, financial independence for women, whether they’re married or not, is essential.

… a lack of education limited the prospects for children, especially girls.

My father was equally insistent. His father had done his best to put him and his siblings through school, and he wanted the same for us. Like my mother, he saw how a lack of education limited the prospects for children, especially girls. He wished to empower my two sisters and me to grow up to be strong women who knew their rights and could assert them to attain a better position in society. Like me, he received his degree from MUBS [Makerere University Business School].

My parents’ passion for education has extended not only to their five children, but to three of our cousins, whose school fees they contribute to, and whose education and prospects they care about as much as ours. As for my siblings: my sister Clare is at university studying to be a veterinarian while Joan finished high school in 2019 and earned Government sponsorship for university. Paul Christian has passed into the last two years of secondary school, and Trevor is in his sixth year of primary school.

Educating girls is not a high-tech or new idea, and has been a pillar of global development policies for decades. In fact, you’ll likely have heard many leaders, women and men, testify to how important it is for girls to be in classrooms on an equal basis with boys. Uganda has mostly reached parity between girls and boys in primary school education. That’s an achievement, of course, but many thousands of girls and boys still aren’t in classrooms, and many girls, like my mother in her generation and some others in my extended family now, leave school before they complete their secondary education. That means relatively few Ugandan girls will attend university. When I was a student at MUBS, I saw plenty of young women in my classes. Even though there were many women at the university, there are many more who aren’t.

Of course, I care about boys’ education as well, and with two brothers, I have to. But across sub-Saharan Africa, at least 33 million girls who could be in primary and lower secondary school aren’t (equivalent to elementary and middle school and the first two years of high school). More than 50 million girls in the region are missing out on receiving an upper secondary school education (equivalent to the last two years of high school in the US or the sixth form in the UK). Around the world, more than 130 million girls aren’t in school and should be. If they had the chance, how many of these young women could be teachers, lawyers, doctors, NGO staffers, members of parliament, or climate scientists?

I think of it like this: girls and women are more than half the world’s population. If we are to successfully address the climate crisis, we need women in the rooms where decisions are being made that affect the climate (and almost all decisions now do). Educating girls brings them into those rooms, and expands the number and approaches of possible decision-makers and solutions.

At the moment, neither the access nor the positive outcomes that would result are happening fast enough. This reality is partly a result of girls’ disempowerment. I’m certain there are tens of millions of girls-and there are countless across Africa-who’d love to study through high school and even university. But many others are doubtful about their prospects and their own capabilities: My mom didn’t make it even this far in school, they tell themselves, so what makes me think I can make it to that level, or even further? You’re a rural girl, the voice whispers, you probably won’t go anywhere in life, even with some education. Why keep going?

If you don’t marry, have a child, and settle for a life of motherhood on a farm, scrabbling for food and fuel for your family, what options await you? You could move from your village to Kampala and work as a maid in the home of a wealthier family.

Perhaps that’s the life of the young woman who’s walking by as we’re holding our placards at a strike. What are they doing? she might ask herself, with a mixture of curiosity and puzzlement. But there’s no time to think more; she’s likely in a hurry, seeking the fastest ways of securing the household items her employer has requested. So, she gets into a matatu (public mini-bus) and heads back to prepare dinner, or wash the floors, or clean the family’s clothes. Honestly, I can’t see her paying much attention to us at all.

Could someone like her, let alone a young woman in a village, become a climate activist? How would she have the time? Practically, she’d probably only have a flip phone, not the smart-phone so many of us now carry. That would make accessing the Internet difficult and expensive, so she’d be disconnected from what’s happening in the wider world. By the time she’d turned twenty, she’d probably be looking for another job. Her employer, worrying that her husband might now look at the young woman with sexual interest, would dismiss her. This is something that happens all the time. Then she would be struggling to find a new source of income and some stability.

Perhaps it’s not the worst fate, but is it really all we want for those girls? To me, these are “survival” lives. Would these young women have chosen these futures if other paths had been open to them, like finishing secondary school, maybe completing a university degree, then getting a job and attaining financial independence, or even becoming engaged in activism?

Covid and the consequences of climate change have intensified pressures on households… School fees, especially for girls, have become a luxury…

It’s a depressing reality that the Covid pandemic has made situations such as I’ve described even worse, and in the same parts of the planet where the climate crisis is a daily emergency. Covid and the consequences of climate change have intensified pressures on household incomes across Africa, Latin America, and Asia. School fees, especially for girls, have become a luxury that has to be cut from the family budget, as it was for Hilda Nakabuye. Millions of girls, as well as many boys, may never return to schools once they’ve fully reopened, and the hard-fought gains in girls’ education made in recent decades may be diluted. We may never know for sure how many children and adolescents have been affected, nor be able to add up all the costs of the pandemic to them, to society, and to the climate.

Excerpted from A Bigger Picture: My Fight to Bring a New African Voice to the Climate Crisis © 2021 by Vanessa Nakate (). Reproduced by permission of Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. All rights reserved.