As Australia experiences its “most dangerous bushfire week” ever, according to firefighting chiefs, an expert panel at the University of Sydney discussed how to respond to such threats globally and their possible armed conflict consequences.

brought together Ole Waever, Professor of International Relations at the University of Copenhagen, Jess Miller, Councillor at the City of Sydney Council, and Olivia Arkell, a fourth-year law student at the University of Sydney and the president of .

Moderated by , an international relations scholar in the , the panellists explained how climate change could contribute to armed conflict, and proposed how politics might change in the face of ‘climate emergency’ battles.

Two kinds of climate security

Professor Waever first outlined the two main climate security hazards: armed conflict and climate change in itself. In regard to the former, there is statistical evidence tying climate change to war, with migration as the catalyst.

“Last year, 17 million people migrated for climate change-related reasons. By 2050, this figure is expected to be over 150 million, and, if the planet warms by three degrees, it could become billions,” Professor Waever said.

“While migration it itself wouldn’t cause conflict, it could aggravate existing tensions, whether ethnic, religious, economic, or territorial.

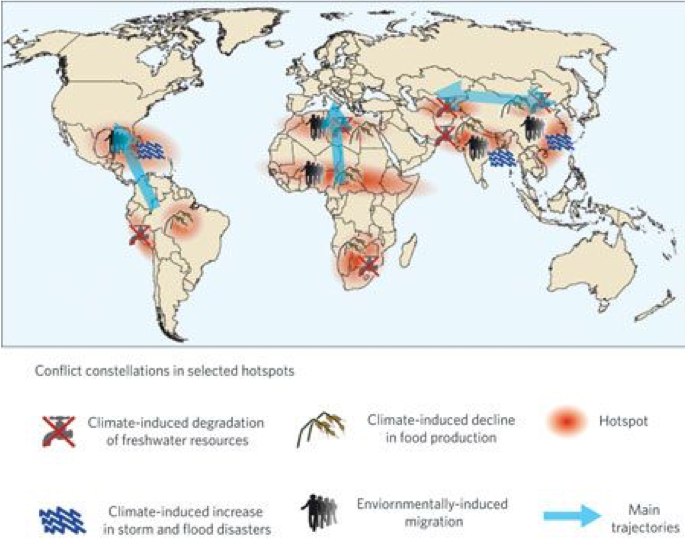

“This could turn into violent conflict that would mostly affect the global south (South East Asia and Africa).”

‘World in transition: climate change as a security risk’. Credit: German Advisory Council on Global Change (WBGU), 2007.

Climate change itself as the security threat is not a new concept, Professor Waever continued.

“At a 2007 meeting of the UN Security Council, climate change was on the agenda.”

Despite this, many security experts as well as environmentalists view security as strictly a military matter, and therefore do not embrace its application to climate change.

Professor Waever disagrees with this stance. Yet he thinks that classifying climate change as an existential threat that requires extraordinary measures, akin to terrorism in 2011, may require democratic upheaval.

“The biggest cost of dealing with climate change might be political. It might have to be top down, and not every country will agree with it,” he said.

Beyond politics?

Have we exhausted our options for dealing with climate security politically? As indicated, Professor Waever doesn’t think so. “We have to get to political decisions, like regulating the price of carbon,” he said.

“This is achievable; look at LED lightbulbs being enforced thanks to regulations.

“The political needle on climate change is moving forward, especially this year with school students striking. Soon, politicians will have to position themselves between doing something and doing everything.”

Associate Professor Epstein similarly believes in the power of politics to drive action against climate change. On the one hand, she noted a closed-door meeting between the Australian leadership and Chief of the Defence Force, General Angus Campbell, in September, where General Campbell warned of the potential of climate change to exacerbate conflict due to natural disasters becoming more frequent and severe.

On the other hand, she lamented the government’s inertia on the issue: “It is more than inaction; it’s an attempt to prevent action. What will they do next – get rid of fire ratings?”

“For young people, it’s really scary”

Councillor Jess Miller and law student Olivia Arkell also commented on the lack of political will to confront climate change.

“For young people, it’s really scary,” 24-year-old Ms Arkell said. “The government is becoming less democratic, with proposed sanctions on protesters, and the government’s subsidisation of coal.”

People power

Councillor Miller thinks a conversation about ‘climate change’ per se is futile. “At this point, we need to talk about resilience and equity,” she said. For example, there is a possibility of heat-related conflict in Western Sydney, where the average temperature is nine to 12 degrees higher than in coastal areas; people are less likely to be able to afford air-conditioning; and there is less social cohesion. “We need to be aware that we don’t live in isolation,” she said.

As such, she is increasingly speaking to her constituents about topics they care about, such as property prices, and framing these in relation to climate change. “My tactic is to understand where people come from at a deep, emotional level,” she said.

“This is how we will get to the government – will people’s houses be insurable once they’ve burned down? If not, there could be a property crisis.”

Another tactic is to look to leadership in the private sector, which Councillor Miller thinks is currently more effective in relation to climate change action.

“Look at people like [Atlassian co-founder] Mike Cannon-Brookes and Elon Musk,” she said.

“What does that mean for democracy? Maybe it’s time we break the system and rebuild it.”

Ms Arkell is also optimistic about mobilising people power. “If we’re disillusioned with the government, we all need to be doing a little bit more,” she said.

“Look at your sphere and ask yourself: ‘what can I do that is a bit more than what I’m already doing?'”