Corals might look like plants or rocks forming on the ocean floor, but they are actually a type of marine animal with a fascinating lifecycle. Each colony of corals is a collection of tube-shaped creatures, called polyps, which together form the largest coral reef system on the planet: the Great Barrier Reef.

Corals are special in their development from infancy to adulthood. For a few days each year, when conditions are just right, Australia’s largest living icon bursts into new life in one of the most extraordinary natural phenomena on the planet known as coral spawning. Each step of their development from spawning to fertilisation, settlement and budding poses a different set of threats which can challenge their survival. This lifecycle also breeds new hope for a new generation of corals on our Reef.

Let’s dive deeper into each stage of coral development:

#Coral spawning

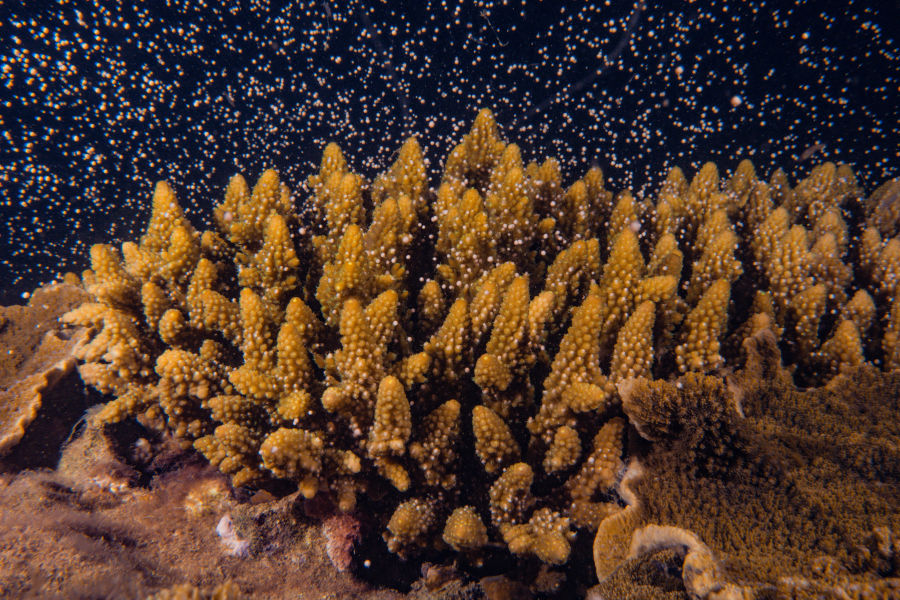

Many coral species on the Great Barrier Reef are known as broadcast spawners. As these species of corals reach adulthood and when conditions are just right, they produce reproductive bundles made up of eggs and sperm. For a few days once a year, different pockets of our Great Barrier Reef will synchronise the release of these reproductive bundles into the water to produce millions of baby corals. Spawning typically occurs a few days after the full moon in October or November, and can vary according to location, water temperature and the tides.

Once the bundles have been released, they rise to the ocean’s surface where fertilisation begins and baby corals are formed. From here, a budding coral’s challenges are just beginning. By spawning on mass, corals increase the likelihood of finding a matching bundle from the same species to fertilise. Other external factors like ocean currents and predation can impact their chances of finding their mate on the surface, which is why we’re using methods like Coral IVF to increase their chances of love.

While spawning is key for the reproduction of future coral generations, in some cases fertilisation can occur internally in the polyp. Sperm released from the mouth of another polyp can merge with an egg to form a larva. Once it’s mature enough, the larva will be released into the water. Corals can also reproduce asexually by budding or fragmentation whereby new polyps or colonies break off from parent polyps to form new colonies.

Corals synchronise the release of reproductive bundles into the water to produce millions of baby corals.

#Fertilisation and settlement of baby corals

On the surface, if the reproductive bundles have found their mate, they fertilise. Just a few hours later the eggs begin to develop into free-swimming larvae, which can drift for days on the surface searching for the perfect spot to settle.

When the larvae are mature enough, they will sink to the sea floor. If they are lucky, they will attach to a suitable surface. In some instances, they can be washed out to sea, fall victim to birds or fish, or land on an unsuitable surface such as coral rubble.

If they find a suitable surface, the larvae will settle and begin a remarkable metamorphosis to become polyps.

Free-swimming larvae settles on a suitable rock surface. Credit: Peter Harrison.

#Coral cloning

At first, baby corals that have fixed and developed on a stationary surface consist of a singular module or polyp. As the polyp grows, it undergoes a process known as budding, where it replicates itself by dividing into genetically identical clones. They continue to divide and grow, in some cases, breaking off a polyp to form new corals and continuing their life to become new juvenile corals.

These new polyps create a network of interconnected colonies and depending on where the coral lands, they can grow out indefinitely or until they hit a barrier. The growth of a coral from settlement to juvenile corals can take years.

Polyps replicate itself by dividing into genetically identical clones.

#The adulting phase

In the longest stage of the coral’s lifecycle, the coral polyp will continue to develop until it forms a mouth and tentacles. Tiny marine algae called zooxanthellae attach and create a mutually beneficial relationship that encourages the polyp to harden and calcify. This algae also helps the coral survive long into maturity and can give corals their colour.

Like most living organisms, corals take a while before they can reproduce. Branching corals normally take a few years while brain corals, which grow at a slower rate, can take about eight years before reaching sexual maturity. Once they do, they can produce reproductive bundles that restart the coral’s life cycle.

Branching corals may normally take a few years before they can begin to reproduce.

#Spawning is key to restoring the Reef

Spawning events are an exciting and busy time of year for Reef scientists, providing them with an opportunity to fast-track world-leading restoration efforts. They are also an extraordinarily narrow window for reef research and restoration efforts, reproducing for just a few days each year. Research teams work around the clock to collect spawn, and use it to grow new, resilient corals on the Reef or in special aquariums on land.

During annual coral spawning events, our researchers capture the coral eggs and sperm from healthy reefs to rear millions of baby corals in specially-designed floating pools on the Reef, and in tanks in a process called Coral IVF. They use the pools to encourage fertilisation and when they are mature enough, they are delivered to damaged reefs where they can attach and grow. The coral larvae settle onto those reefs and in years to come they will spawn and produce their own coral babies, re-establishing the breeding population of damaged reefs. Coral IVF is just one of the innovative way we’re getting the most out of coral spawning.

News ·