Each year, when conditions are just right, Australia’s largest living icon bursts into new life in one of the most extraordinary natural phenomena on the planet. Different pockets of our Great Barrier Reef synchronise the release of millions of eggs and sperm into the water to produce baby corals.

This natural reproductive process, known as coral spawning, is an opportunity to fast-track world-leading . Corals reproduce for just a few days each year and research teams work around the clock to collect spawn and use it to grow new, resilient corals on the Reef or in special aquariums on land. It’s an exciting and busy time of year for Reef scientists as spawning provides them with an extraordinarily narrow window for reef research and restoration efforts.

Let’s dive deeper to discover how these interventions are having a direct impact on coral development and the health of our Great Barrier Reef.

#Into the wild

For a few days once a year, our Great Barrier Reef synchronise the release of eggs and sperm, into the water. Once they have been released, they rise to the ocean’s surface where each must find another from the same species to fertilise. If successful, baby corals form. While corals increase their chances of finding a match by spawning en masse in open water, only an estimated one in a million fertilised eggs (0.0001%) survive to become coral.

The rest either don’t find a match, are washed out to sea by ocean currents and tides, or fall victim to predation by marine creatures such as fish. Baby corals that survive to settlement must find a stable spot on the ocean floor that is clear of algae and sediment, but with enough sunlight to grow, otherwise they perish.

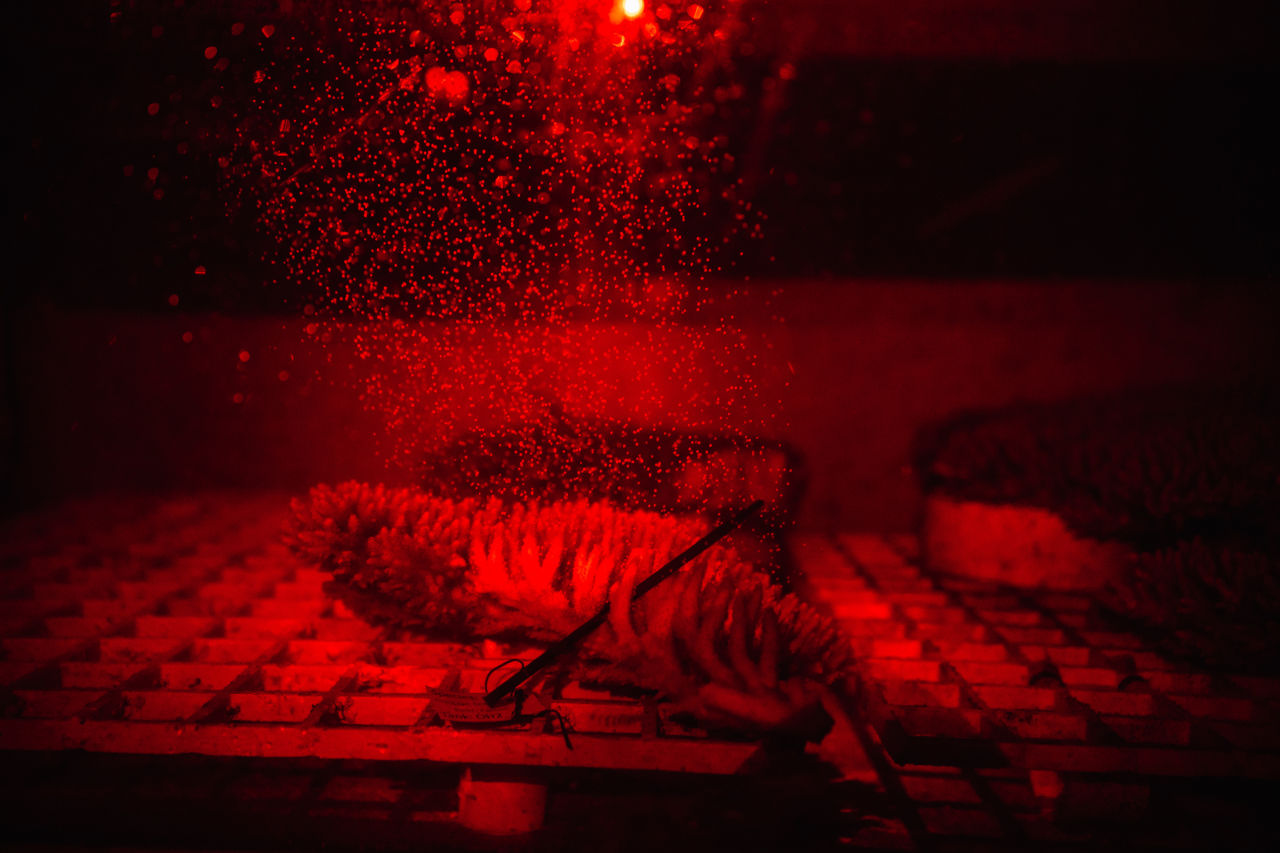

RRAP scientists simulate coral spawning for cryopreservation collection. Credit: Gary Cranitch.

#Coral IVF

Scale and numbers matter for the future health of our Reef and so scientists and engineers are working to increase their chances of fertilisation in a more controlled environment.

To help enhance corals’ natural reproduction process, researchers capture millions of tiny coral eggs and sperm from healthy reefs and collect them in specially designed floating pools on the Reef and in tanks. We call this technique ’‘ as the larvae pools are likened to floating nurseries that encourage a higher rate of fertilisation within a confined and protected space.

Baby corals reared using Coral IVF have an improved chance of survival with an aim to achieve a 1 in 10,000 (0.01%) or greater survival rate. These baby corals remain in the pools for a few days and when they are mature enough, researchers release the microscopic babies into the water near the reef floor, where they settle, attach and begin to grow.

This innovative coral larval restoration technique was successfully pioneered on the Reef by Southern Cross University’s Distinguished Professor Peter Harrison to boost the number of coral babies that survive each annual spawning. Early indications show that Coral IVF increases the volume of coral babies settling on the Reef, accelerating and amplifying nature’s work. This solution could be applied to coral reefs worldwide, offering hope for restoring and repairing damaged coral populations globally.

The Boats4Corals project in the Whitsundays is just one project helping scale up restoration. The Boats4Corals crew is made up of local tourism operators, Traditional Owners, government agencies, and recreational boaters – all trained in the Coral IVF method; from identification of spawning slicks, to releasing coral larvae from floating nursery pools onto the Reef.

The Boats 4 Coral team and larval pool on the Whitsundays. Credit: Johnny Gaskell.

#Coral Aquaculture

Coral aquaculture is the process of raising large numbers of healthy corals in a specialised aquarium by replicating natural coral reproduction and growth. Spawning can be replicated in aquarium settings with sections of adult corals that have been collected from the Reef, or corals that have been raised from ‘birth’ in tanks on land.

The survival rates are much higher using aquaculture as the whole process is undertaken in a controlled environment with estimated survival rates closer to 1 in 4. By propagating corals in aquaculture, we can control conditions and thereby fast-track our understanding of factors that impact coral survival and growth, and how to help corals better cope with increased ocean temperatures.

Coral Spawning at Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) ³Ô¹ÏÍøÕ¾ Sea Simulator. Credit: SkyReef Photos and AIMS.

#The need for well-researched intervention

The Great Barrier Reef has suffered three mass bleaching events in the past five years. We know that warming temperatures are already locked into the earth’s climate system over the coming two to three decades which will threaten the ability of reefs to recover.

Spawning holds the key to unlocking natural restoration and new generations of corals now and into the future. Because of this, it is integral that we understand how we can harness and enhance the reef reproductive process under different environmental and climate conditions. This is the critical research and development behind the Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program. We’re helping to investigate the most efficient, cost-effective and ecologically safe methods for a warmer future.

With such a narrow spawning window each year, we need to mobilise efforts to get the most impact from it. Our goal is that large-scale, well-designed restoration initiatives can help corals adapt to this changing environment. We know that future reefs will be different to the reefs we have today, but our aim is to ensure that the ecosystem remains healthy and diverse.

News ·

Main image of soft corals spawning on the Great Barrier Reef. Credit Calypso Productions.