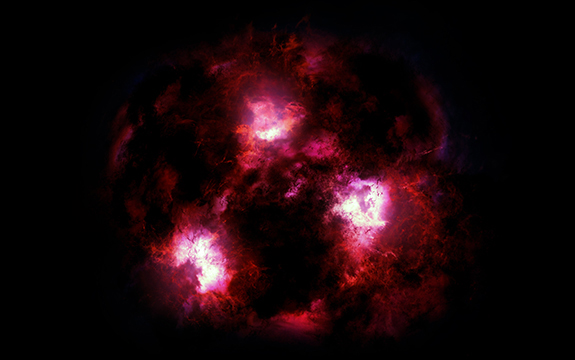

Artist’s impression of what a massive galaxy in the early Universe might look like. The galaxy is undergoing an explosion of star formation, lighting up the gas surrounding the galaxy.

Astronomers have accidentally discovered the footprints of a monster galaxy in the early Universe that has never been seen before.

Like a cosmic Yeti, these galaxies have been regarded by the scientific community as folklore, given the lack of evidence of their existence. Now, for the first time astronomers in the US and Australia have managed to snap a picture of the beast. The discovery provides new insights into the first growing steps of some of the biggest galaxies in the Universe.

Using the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA), a collection of 66 radio telescopes high in the Chilean mountains, Dr Christina Williams, lead author of the study, noticed a faint light blob in new sensitive observations. Strangely enough, the shimmering seemed to be coming out of nowhere, like a ghostly footstep in a vast dark wilderness.

“It was very mysterious because the light seemed not to be linked to any known galaxy at all,” says Dr Williams, a ³Ô¹ÏÍøÕ¾ Science Foundation postdoctoral fellow at the University of Arizona Steward Observatory.

“When I saw this galaxy was invisible at any other wavelength, I got really excited because it meant that it was probably really far away and hidden by clouds of dust.”

The researchers estimate that the signal came from so far away that it took 12.5 billion years to reach Earth, therefore giving us a view of the Universe in its infancy. They think the observed emission is caused by the warm glow of dust particles heated by stars forming deep inside a young galaxy. The giant clouds of dust conceal the light of the stars themselves, rendering the galaxy completely invisible.

“We figured out that the galaxy is actually a massive monster galaxy with as many stars as our Milky Way but brimming with activity, forming new stars at 100 times the rate of our own galaxy, says study co-author, Professor Ivo Labbé from Swinburne University of Technology.

Solving a cosmic puzzle

The authors say the discovery may solve a long-standing question in astronomy. Recent studies found that some of the biggest galaxies in the young Universe grew up and came of age extremely quickly, a result that is not understood theoretically.

Massive mature galaxies are seen when the Universe was very young. Even more puzzling is that these mature galaxies appear to come out of nowhere: astronomers never seem to catch them while they are forming.

Smaller galaxies have been seen in the early Universe with the Hubble Space Telescope, but they are not growing fast enough to solve the puzzle. Other monster galaxies have also been previously reported, but those sightings have been far too rare for a satisfying explanation.

“Our hidden monster galaxy has precisely the right ingredients to be that missing link because they are probably a lot more common,” explains Dr Williams.

An open question is exactly how many of them there are. The observations for the current study was made in a tiny part of the sky, less than 1/100th the size of the full Moon. Within the Yeti analogy, finding footprints in a tiny strip of wilderness would either be a sign of incredible luck, or that monsters are literally lurking everywhere.

Dr Williams says researchers are eagerly awaiting the launch of NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), scheduled for March 2021, to investigate these objects in more detail.

“JWST will be able to look through the dust veil so we can learn how big these galaxies really are and how fast they are growing, to better understand why models fail in explaining them.”

But for now the monsters are out there, shrouded in mystery.

The research has been published in the .