Ancient protein evidence shows milk consumption was a powerful cultural adaptation that stimulated human expansion onto the highland Tibetan Plateau

The question of how prehistoric populations obtained sustainable food in the barren heights of the Tibetan Plateau has long attracted academic and popular interest. A new study led by scientists from the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology, Germany (formerly Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History), the Center for Archaeological Science at Sichuan University, China, and the Tibetan Cultural Relics Conservation Institute, China highlights the critical role of dairy pastoralism in opening the plateau up to widespread, long-term human habitation.

Modern pastures on the highland Tibetan Plateau

© Li Tang

The Tibetan Plateau, known as the “third pole”, or “roof of the world”, is one of the most inhospitable environments on Earth. While positive natural selection at several genomic loci enabled early Tibetans to better adapt to high elevations, obtaining sufficient food from the resource-poor highlands would have remained a challenge.

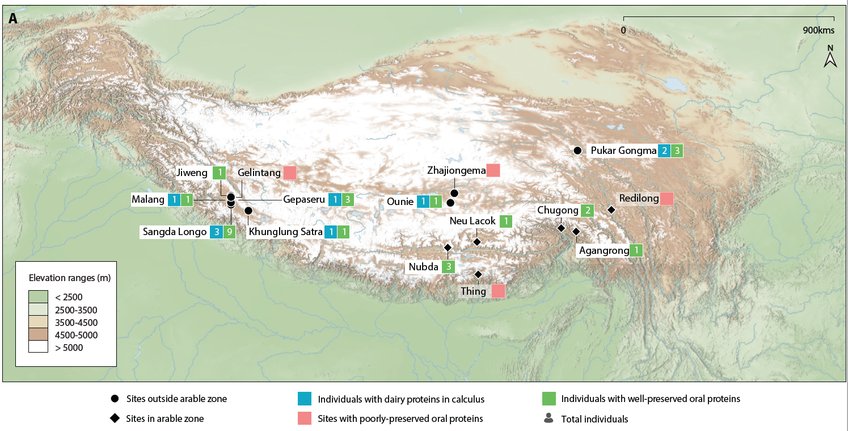

Now, a new study in the journal Science Advances reveals that dairy was a key component of early human diets on the Tibetan Plateau. The study reports ancient proteins from the dental calculus of 40 human individuals from 15 sites across the interior plateau.

“We tried to include all the excavated individuals with sufficient calculus preservation from the study region,” states Li Tang, lead author of the study. “Our protein evidence shows that dairying was introduced onto the hinterland plateau by at least 3500 years ago,” states Prof. Hongliang Lu, corresponding author of this study.

Dental calculus of the highest altitude individual investigated in the study (cal. 601-758 CE)

© Li Tang

Ancient protein evidence indicates that dairy products were consumed by diverse populations, including females and males, adults and children, as well as individuals from both elite and non-elite burial contexts. Additionally, prehistoric Tibetan highlanders made use of the dairy products of goats, sheep, and possibly cattle and yak. Early pastoralists in western Tibet seem to have had a preference for goat milk.

“The adoption of dairy pastoralism helped to revolutionize people’s ability to occupy much of the plateau, particularly the vast areas too extreme for crop cultivation,” says Prof. Nicole Boivin, senior author of the study.

Tracing dairying in the deep past has long been a challenge for researchers. Traditionally, archaeologists analyzed the remains of animals and the interiors of food containers for evidence of dairying, however the ability of these sources to provide direct evidence of milk consumption is often limited.

“Palaeoproteomics is a new and powerful tool that allowed us to investigate Tibetan diets in unprecedented detail,” says coauthor Dr. Shevan Wilkin. “The analysis of proteins in ancient human dental calculus not only offers direct evidence of dietary intake, but also allows us to identify which species the milk came from.”

Map of samples studied in this article

© Michelle O’Reilly und Dovydas Jurkenas

Tibetan pastoralist in a winter pasture churning yak milk to make butter and cheese

© Li Tang

“We were excited to observe an incredibly clear pattern,” says Li Tang. “All our milk peptides came from ancient individuals in the western and northern steppes, where growing crops is extremely difficult. However, we did not detect any milk proteins from the southern-central and south-eastern valleys, where more farmable land is available.”

Surprisingly, all the individuals with evidence for milk consumption were recovered from sites higher than 3700 meters above sea level (masl); almost half were above 4000 masl, with the highest at the extreme altitude of 4654 masl.

“It is clear that dairying was crucial in supporting early pastoralist occupation of the highlands,” notes Prof. Shargan Wangdue. “Ruminant animals could convert the energy locked in alpine pastures into nutritional milk and meat, and this fueled the expansion of human populations into some of the world’s most extreme environments.” Li Tang concludes.