Rome – The community of the world’s nations adopted a landmark framework to support global biodiversity on 19 December, and the agreement contains significant contributions from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), committed to make sure that the needs and impacts of agrifood systems are given due consideration.

The was approved at the UN Biodiversity Conference summit after marathon negotiations at the headquarters of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), the multilateral treaty tasked with the conservation of biological diversity and the sustainable use of its components.

The document explicates the four goals and 23 targets for 2030 adopted, which include a pledge to protect 30 percent of the Earth’s lands, oceans, coastal areas and inland waters, to repurpose $500 billion in annual government subsidies so that they provide incentives rather than trigger harm for biodiversity goals, and to create a Special Trust Fund under the aegis of the Global Environment Facility () to support implementation of the new Framework.

“The COP15 summit was a success as a framework for the future was agreed,” said FAO Deputy Director-General Maria Helena Semedo, who headed FAO’s delegation at the summit and is responsible for the Natural Resources and Sustainable Production stream at the UN agency. “Now we have measurable objectives and dedicated financial mechanisms, which is a big step forward.”

Hailed by UN Secretary-General António Guterres as the outline of a , the framework culminates years of multifaceted work by FAO, which at the COP13 in 2016 was mandated to develop and manage a to foster dialogue between the environment sector, often focused on conservation, and the agricultural sectors, whose function of feeding the world inevitably has a large impact on the world’s natural resources.

FAO distributed a white paper to COP15 delegations and the Organization’s experts were repeatedly asked for technical inputs during the just-concluded CBD negotiations.

to highlight specific topics. These included the importance of mountain areas, of forest ecosystem restoration, of the role and knowledge of Indigenous Peoples, of the roles of wild meat and sustainable wildlife management, of pollinators, fisheries, of assuring that finance flows are consistent with nature-positive pathways, and of the prospects for evidence-based to contribute to and accelerate global biodiversity mainstreaming.

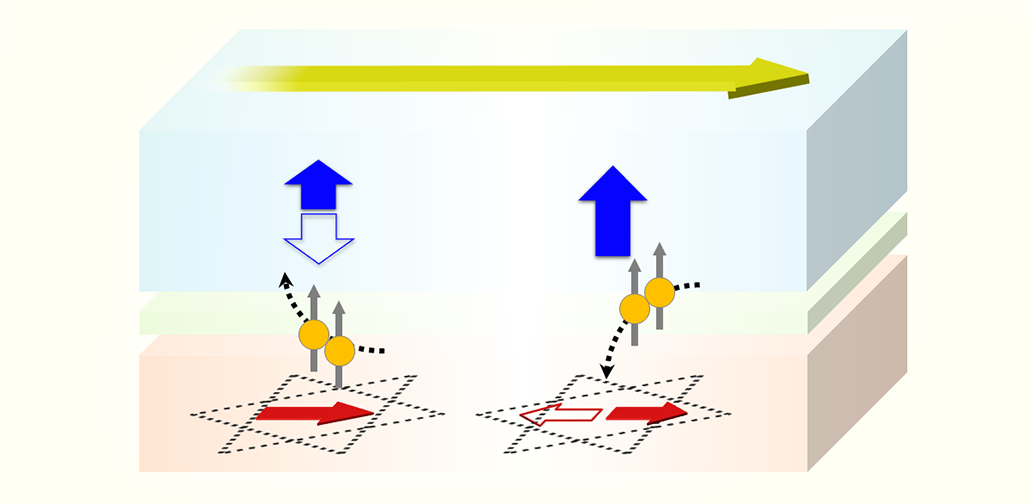

At COP15 FAO also launched the Global Soil Biodiversity Observatory (), which aims to deepen knowledge about the critical functions of what Semedo calls the biodiversity “that we do not see”. Only a tiny fraction of soil organisms have been identified to date, and the GLOSOB observatory offers an urgent opportunity for countries – and their farmers large and small – to contribute to measuring and monitoring what is happening on the level where food begins.

FAO and sustainable utilization

While many biodiversity conservation advocates have long favoured expanding protected areas, FAO champions a view where many of these areas are critical for the food security and cultural integrity of the world’s peoples, underscoring the importance of managing multiple goals in a holistic way.

Moreover, as more than a third of the Earth’s surface is devoted to agriculture, and biodiversity itself comprises crop varieties and livestock breeds as well as microorganisms in the soil, agrifood systems are essential parts of an effective and efficient approach to protecting global biodiversity. A wealth of evidence suggests that assuring sustainable utilization is often a more fruitful path than rigid protection.

So while agrifood production must be made more sustainable, conservation must also be sustainable.

“It is important to grasp that while agrifood systems can reduce biodiversity, ultimately they depend on it, so there is a lot of room for mutual and symbiotic benefits,” said FAO’s Semedo.

“Any solution to stop and reverse biodiversity loss will require agrifood system transformation, and the Global Biodiversity Framework will not succeed without the engagement of the food and agriculture sectors,” said Frederic Castell, Senior Natural Resources Officer and leader of FAO’s work on biodiversity mainstreaming. Agrifood systems are central to around half the targets of the new Framework, he added.

Target 10 of the Framework captures the spirit of that point.

Promises and challenges

The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework contains numerous specific elements that have been driving FAO’s work and will add new tasks.

Creating the canopy offers the advantage of being implemented quickly. FAO has a with GEF, amounting to more than $7.7 billion in resources for 230 projects in 124 countries, and has a central role in supporting Members in accessing resources and providing expertise to pursue their goals and pledges.

Target 7 of the new Framework is focused on sharply reducing pollution risks for biodiversity, including those from excess nutrients from fertilizers and chemicals from pesticides. Achieving this will require concerted expansion of integrated pest management for crops, as well as working towards eliminating plastic pollution. FAO is a center of knowledge on , has rolled out new data sets to help , has , conducted in-depth studies on and earlier this year was .

Target 18 calls for the elimination, phase-out or reform by 2030 of $500 billion in annual incentives and subsidies that are harmful for biodiversity and scaling up positive incentives. That pledge is very much in line with a benchmark and partner UN agencies.

Other areas where FAO is well positioned to support its Members to implement the framework include , especially as co-lead of the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration with UNEP, combating invasive species and the access and sharing of benefits arising from the , including digital sequence information and traditional knowledge associated with them.