Searching for a sane and healthy response to nuclear and climate crises

By Rob Delves, Green Issue Co-editor

Hope, denial, fear, despair…. Is any one of these (and several other) emotional responses to climate change more realistic and better for one’s emotional health? In her highly recommended book How to talk About Climate, the Australian social researcher Rebecca Huntley takes us on both a personal and an analytical journey that argues there’s no simple answer to the question of which emotions are better than others. I’ve also thought hard about the feelings that well up inside me about living in a climate emergency. I’d like to share my experiences and reflections – it turns out that these emotions are remarkably similar to those that I have experienced around the threat of nuclear conflict.

In London in the early 1980s, several of my friends, especially young mothers, began confessing that fear of nuclear annihilation was eating into their souls. There were plenty of developments stoking those fears. “Star Wars” Ronnie Reagan was one huge reason and the British PM Margaret Thatcher certainly wasn’t holding him back. Promising moves towards halting the development and testing of nuclear weapons had been replaced by boasting about the increasing power of new weapons. For many of us the sickest and most obscene were the headlines about how clever the latest hydrogen bombs were because they wiped out all living things but left buildings largely undamaged: a truly amazing ethical advance for mankind. Even more alarming, so we were constantly told, was that we were falling behind the Russians in the “essential” task of maintaining equal nuclear capability – as in, Panic Stations, they have enough weapons to destroy every one of us ten times over, whereas we can only annihilate them nine times over.

And the fear-inducing reasons kept piling up. , a powerful and widely discussed BBC film argued that, given the power of the newest weapons, even a limited nuclear exchange would devastate major cities beyond anything that their nation’s health and emergency services could cope with. Moreover, it was very likely it would plunge most of the planet into a “Nuclear Winter” that would kill millions of us by starvation and unbearable cold over several years. Just one modern bomb had the power to meltdown the entire London Tube system .

.

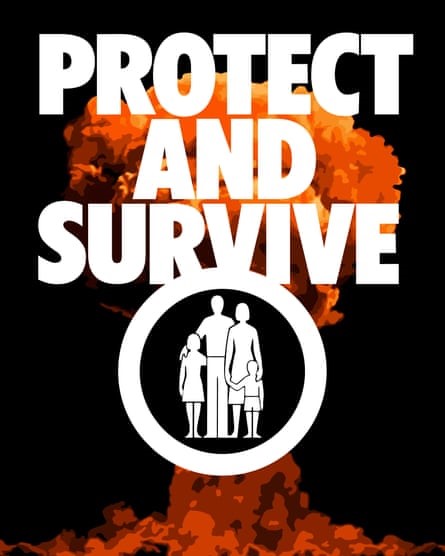

But fear not – your government has everything under control, thanks to a booklet posted to every British home. Entitled Protect and Survive, it explained how we could all ensure our safety in the event of a nuclear attack by sticking cardboard onto our windows and moving into the centre of our living rooms. And sleep soundly in the middle of the room while the first bomb melted the entire underground but our cardboarded windows protected us from all the following ones.

My friends acknowledged that dwelling on their fears wasn’t good for their physical and mental health, but they argued that deliberately denying the dire situation was an even less healthy response. In fact, they questioned whether, given the twin realities of terrifying weapons and cavalier conflict-stoking political leaders, fear and despair were the only appropriate and healthy responses. However, sleep didn’t come easier just because their agonising fears were somehow saner than what was going on in the minds and souls of the deniers. I never had a clue how to respond, apart from shutting up, listening intently and feeling slightly guilty about not being so consumed by nuclear gloom.

Slow-forward some 40 years and I’m the one asking friends to listen to my fear and despair, this time about climate change. Of course, I’m not the only person trying to deal with a climate-troubled soul. In fact, I realise that several other groups of people, for example young people and climate scientists, have even more reason to despair. Several teachers in their 20s have told me they are thinking hard about not having children for climate reasons. Terry Hughes, one of the world’s leading experts on coral reefs, recently took to Twitter to describe the emotional toll his research on the Great Barrier Reef was taking: “I feel like an art lover wandering through the Louvre…as it burns to the ground…I’m not sure I have the fortitude to do this again.”

As it was with the nuclear war threat, this despair and fear many of us feel is generated by strong evidence: the reality and urgency of climate breakdown combined with responses from Australia’s political leaders that range from outright denial to tokenistic commitments and actions that don’t come anywhere near what the science demands. Listening to Angus Taylor’s assurances that “we are taking responsible actions in line with our Paris commitments” reminds me so much of receiving my personally addressed Protect and Survive booklet from Margaret Thatcher. In both cases, laughter at the absurdity of the offering is the immediate response – and a good laugh helps combat depression, I guess.

As I lie awake at night filled with despair about how badly we are losing this battle, how my generation wasted the 30+ years since scientists first rang the alarm bells, how rapidly the window for action is closing, I’m well aware that this distress isn’t doing my mental and physical health the world of good. Yet what exceedingly unhealthy mental gymnastics are being performed by millions of my generation who hear the science, see the mounting evidence (drought, bushfires, heatwaves, melting ice…) and respond by doing nothing. In a recent Green Issue article, Chris Johansen asks himself a similar question: Most parents, wherever they sit on the political spectrum, want the best for their offspring’s future. It thus emerges as a conundrum as to why parents/grandparents who sincerely wish their children/grandchildren well would condemn them to live in an ever-deteriorating global climate by opposing, or at least being ambivalent to, effective action on climate change.

So, I try reassure myself that this fear and despair is a normal and sane response to what we are facing today. But surely it’s not healthy to lie awake at night entertaining such despair? Fear and despair are certainly destructive of just about everything, including one’s health, if it results in paralysis, denial, giving up, as often seems to happen. There’s a strong whiff of this in what appears to be the latest neoliberal defence for inaction: “it’s too late to do anything.” So, can these dark thoughts eating away at the soul be positive for one’s wellbeing? I take heart from something I’ve heard several times from the ABC radio broadcaster Phillip Adams. He often fondly recalls the 80th birthday press conference of the world-famous cellist Pablo Casals. After despairing at climate change and other the troubles of the world, he paused and then stated his two-sentence conclusion: “The situation is hopeless. We must take the next step”.