Global hazard map of glyphosate contamination in soils.

Agricultural scientists and engineers have produced the world’s first map detailing global ‘hot spots’ of soil contaminated with glyphosate, a herbicide widely known as Roundup.

The map is published as the world’s eyes fall on glyphosate and concerns about its potential impact on environmental and human health. Last year in the US the owner of Roundup, Monstanto (now owned by Bayer), was $US2 billion to a couple who said they contracted cancer from the weedkiller, the third case the company had lost.

This year, Australia is emerging as the next legal battleground over whether the herbicide causes cancer with a for the Federal Court.

Professor Alex McBratney.

“The scientific jury is still out on whether the chemical glyphosate is a health risk,” said , director of the Sydney Institute of Agriculture at the University of Sydney. “But we should apply the precautionary principle when it comes to the health risks.

“And even if no evidence emerges about these risks, it is time for the agriculture industry to diversify our herbicides away from relying on a single chemical.”

The map and associated study have been published in the journal .

Lead author of the paper is from the Sydney Institute of Agriculture and Faculty of Engineering. He said: “Glyphosate is a ubiquitous environmental contaminant. About 36 million square kilometres are treated with 600 to 750 thousand tonnes every year – and residues are found even in remote areas.”

Hot spots

The paper identifies hotspots of glyphosate residue in Western Europe, Brazil and Argentina, as well as parts of China and Indonesia. Contamination refers to concentration levels above the background level.

Associate Professor Federico Maggi.

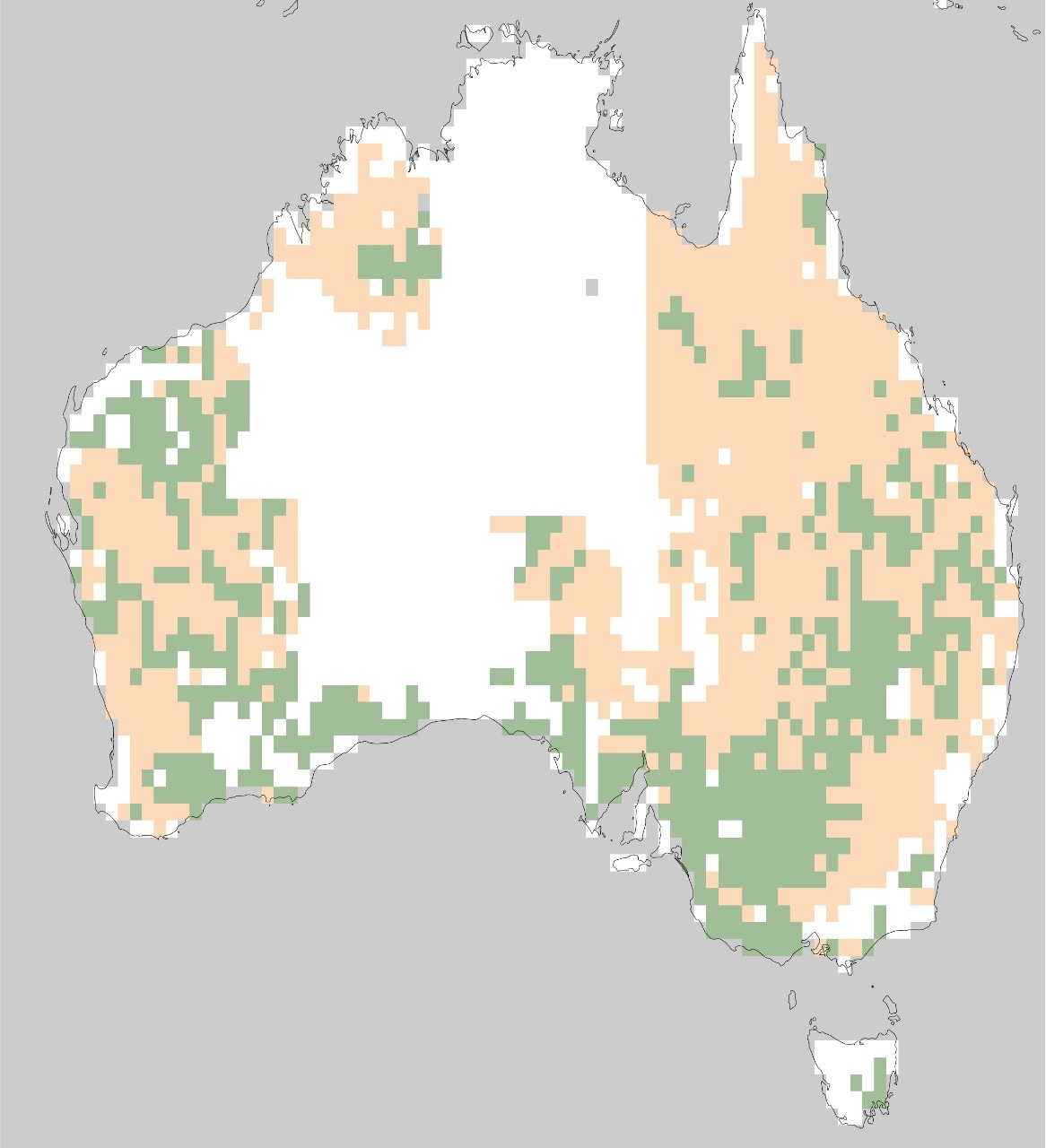

“Our analysis shows that Australia is not a hotspot of glyphosate contamination, but some regions are subject to some contamination hazard in NSW and QLD and, to a lesser extent, in all other mainland states,” Associate Professor Maggi said.

He said that given the widespread use of the herbicide, soil contamination is unpreventable. This is because it is hard to be degraded by soil microorganisms when it reaches pristine environments, or it releases a highly persistent contaminant called aminomethyl-phosphonic acid (AMPA) when it is degraded.

The researchers emphasise that contamination levels do not necessarily equate to any environmental or health risks as these are still unknown and require further study.

“Our recent environmental hazard analysis considers four modes of environmental contamination by glyphosate and AMPA – biodegradation recalcitrance, residues accumulation in soil, leaching and persistence,” Associate Professor Maggi said.

“We found that 1 percent of global croplands – about 385,000 square kilometres – has a mid- to high-contamination hazard.”

He said that contamination is pervasive globally, but is highest in South America, Europe and East and South Asia. It is mostly correlated to the cultivation of soybean and corn, and is mainly caused by AMPA recalcitrance and accumulation rather than glyphosate itself.

“While there are controversial perspectives on the safety of glyphosate use on human health, little is known about AMPA’s toxicity and potential impacts on biodiversity, soil function and environmental health. Much further study is required,” Associate Professor Maggi said.

Poor long-term policy

Professor McBratney said aside from the risks to human health, it is poor long-term agriculture policy to rely on glyphosate as a herbicide.

“Weeds are genetically adapting and building resistance to glyphosate,” he said. “And there is growing evidence that a new generation of precision herbicide application could further improve yields.”

Professor McBratney said Australia was well placed to economically benefit from the development of new herbicides.

“In these times of increasing food demand, relying on a single molecule to sustain the world’s baseload crop production puts us in a very precarious position,” he said. “We urgently need to find alternatives to glyphosate to control weeds in agriculture.”

A portion of the map showing distribution of glyphosate in Australia.