Amie Zarling, a clinical psychologist and associate professor of human development and family studies at Iowa State. Larger image. Chris Gannon/Iowa State University

AMES, IA – A new study from Iowa State University found men convicted of domestic violence were charged with significantly fewer violent and nonviolent charges one year after completing a treatment program developed in Iowa compared to a model used in most other states. Survey data from victims still in contact with the men provided preliminary evidence that the local intervention may also reduce behaviors like physical aggression, controlling behaviors and stalking.

The findings come from the first randomized controlled trial comparing an Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) based program used by the Iowa Department of Corrections with the Duluth Model Men’s Nonviolence Classes.

Amie Zarling, a clinical psychologist and associate professor of human development and family studies at Iowa State, led the , which was published in the Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology and funded by the Department of Justice’s Office on Violence Against Women.

“I’ve waited more than a decade to do this study. Randomized controlled trials are the gold standard method for evaluating program efficacy but are very difficult to implement properly, especially in real-world settings,” says Zarling. “The results suggest that the ACT-based program is an effective treatment for reducing criminal behavior, and most importantly, that the women who are survivors of the domestic violence report that the man who caused harm has significantly decreased his abusive behavior because of the ACT program.”

A 2015 survey from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found in the U.S. had experienced intimate partner violence. This includes physical and sexual violence, stalking and psychological aggression (e.g., coercive tactics). However, experts say domestic violence is chronically underreported, so even this striking number does not represent the full extent of domestic abuse.

Rather than sending men with a first or second domestic abuse charge to prison, Iowa and most other states mandate the completion of a batterer intervention program. The most widely used program, the Duluth Model, stems back to the early 1980s and is grounded in feminist theory.

Advocates of the Duluth Model say the is a sexist society and that for men to change, they need to be re-educated and must unlearn their beliefs.

A new model for Iowa

But when the Iowa Department of Corrections (DOC) conducted an internal evaluation of the Duluth Model in 2009, it found the program did very little to improve domestic assault recidivism compared to no treatment at all. The results reflected similar findings from researchers investigating the effectiveness of Duluth and other batterer intervention programs that adopted a similar approach.

The Iowa DOC decided to look for an alternative and turned to researchers at the University of Iowa where Zarling was a graduate student at the time.

Combining her clinical psychology background with input from criminal justice practitioners, Zarling developed the Achieving Change Through Values-Based Behavior program, or ACTV (pronounced active), which the in 2010 and has since scaled up to use across Iowa. Over 500 staff have been trained in the ACTV model, and approximately 15,000 men charged with domestic abuse have participated in the intervention since 2010.

ACTV is based on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). It’s a cognitive-behavioral approach based on a unified model of human development, behavior change and psychological growth.

“ACT-based programs hold the perspective that there are many contributors to intimate partner violence, including a lack of skills to manage emotions and communicate in a healthy and respectful way, as well as troubling or harmful beliefs and attitudes toward women and toward oneself. A history of trauma, experiencing racial discrimination, attachment difficulties, substance use and even mental health can also be factors,” said Zarling.

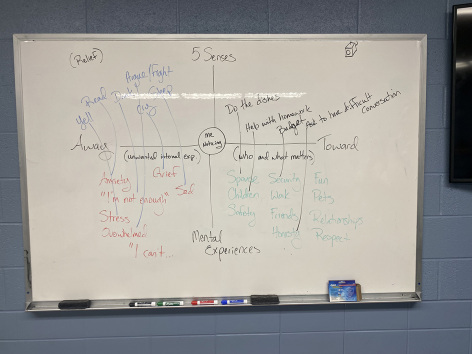

Zarling developed the matrix, an interactive tool facilitators use to help ACTV participants identify how they respond to certain situations and whether those responses move them toward or away from what they value in life. Photo courtesy of Amie Zarling.

Zarling emphasized ACT-based programs are a trauma-informed approach to help people identify their values, the relationships and meaningful parts of their lives, and then build skills to stretch their “psychological flexibility” – the ability to behave in a way that aligns with those values, regardless of the thoughts or feelings that may arise.

“From the ACT perspective, our brains work by adding rather than subtracting, meaning it’s really hard to remove a thought, emotion or feeling that pops up. But with psychological flexibility, someone can notice that thought or feeling and how it’s trying to pull them to behave a certain way, gain some distance from it, and then have the ability to choose more mindfully when responding to that thought or feeling,” said Zarling.

Data collection, findings and limitations

Zarling designed the study to randomly assign 338 men in central Iowa who had been court-mandated to complete 24 sessions of a domestic violence program to ACTV or the Duluth Model.

She found ACTV participants had about half the rate of the violent and non-violent charges, like robbery and drug-related offenses, a year after completing the intervention program compared to the men who had been assigned to the Duluth Model.

Fewer than 13% of the participants in both ACTV and the Duluth model were charged again with domestic assault in the year following the intervention. While recidivism was several percentage points lower for graduates of ACTV (9%), Zarling said the difference was not statistically significant, potentially due to the smaller than expected sample size of the participants. The original plan was to have a sample size of over 400 men, but the outbreak of COVID-19 in 2020 prematurely ended the study.

“But using criminal charges as an outcome is just one piece of the puzzle,” said Zarling. “In some ways, the most important finding from this study is from the victims’ reports, as most domestic abuse is not reported to law enforcement.”

The survey data from victims showed physical aggression, controlling behaviors and stalking behaviors decreased from the men who were in ACTV.

Bridging the gap

Over the last decade, Zarling has helped the Iowa Department of Corrections train ACTV facilitators and provide supervision during their first 24 sessions with participants. She has also provided recommendations based on her research and the research of others.

“Unfortunately, in the domestic violence field, the practitioners are very separate from the researchers, in general, and here in Iowa, I’m trying to change that,” she said. “Being involved with the IDOC ensures a solid researcher-practitioner collaboration and effective community-university partnership.”

But Zarling emphasized she is not beholden to the ACTV model.

“I want to do research that betters the field of domestic violence. If that includes ACTV, that’s great, but if not, that’s OK. I’m following the data,” said Zarling.

With the newly published findings, Zarling sees a path to helping reduce family violence.

This summer, she’ll be conducting a randomized controlled trial of the ACTV program in the prison setting with a second grant from the Department of Justice.

ISU Professors of Human Development and Family Studies Dan Russell and Carl Weems contributed to the study.