New research is exploring low-cost, non-invasive ways to diagnose Barrett’s esophagus, a condition associated with deadly oesophageal cancer, to find effective strategies to identify patients with this condition.

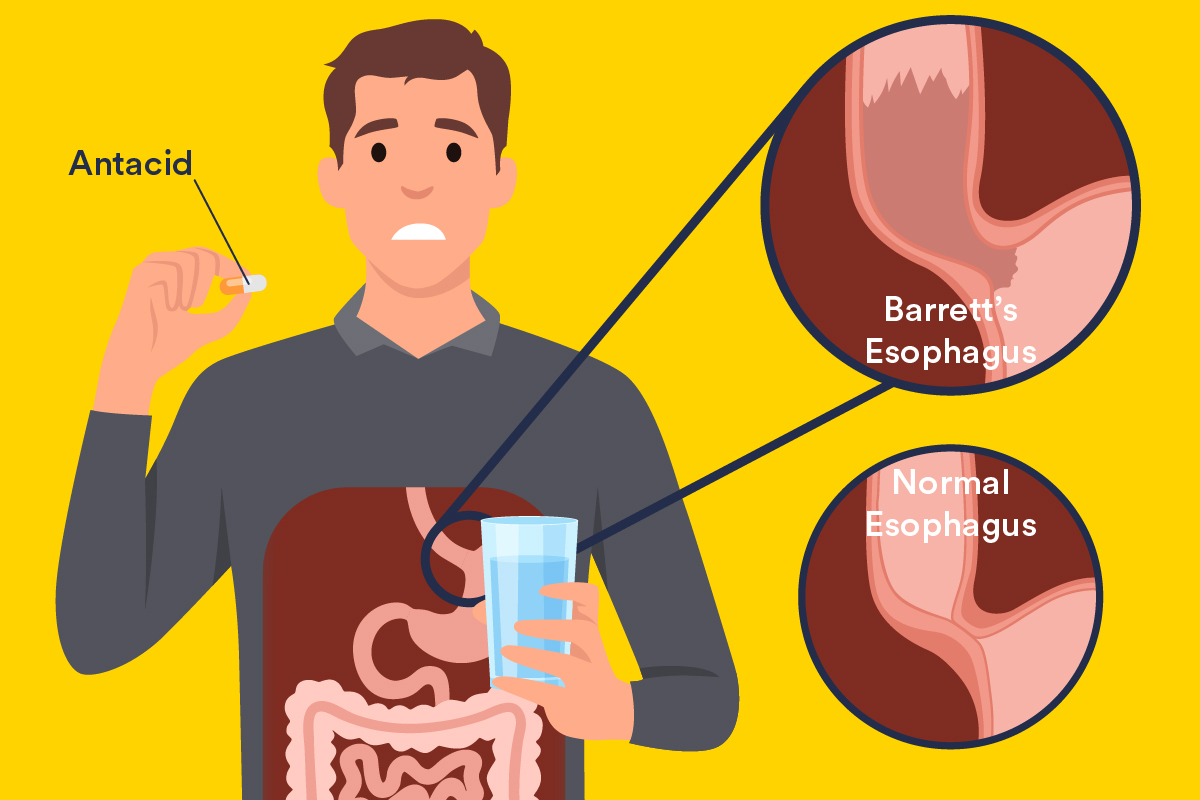

Barrett’s esophagus is a condition where the lining along the oesophagus (food pipe) becomes damaged from prolonged exposure to stomach acid, with lifestyle factors such as drinking and smoking contributing to it.

According to research, between 2-4% of Australians live with Barrett’s oesophagus, most commonly in men over 40 years, with most being unaware of their diagnosis due to unassuming symptoms similar to regular heartburn.

“In most industrialised countries, including Australia, the incidence of oesophageal cancers has increased fivefold in the past 40 years and almost all of these cancers arise from underlying Barrett’s oesophagus ,” says lead author, from the College of Medicine and Public Health.

“Barrett’s oesophagus is important clinically because those who have it are predisposed to oesophageal cancer which remains one of the deadliest forms of gastrointestinal cancer, with a five-year survival rate of about 20 per cent.

“This is relatively low compared to other cancers so hopefully the insights we gain from this research can be translated into better ways of identifying and treating Barrett’s oesophagus to reduce the risk of it developing into oesophageal cancer and increasing patient survival.”

Diagnosis of Barrett’s oesophagus is usually made following an endoscopy, an invasive procedure where a camera looks at the lining of the oesophagus.

The research, published in the Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, suggests using a multi-step strategy to identify Barrett’s’ oesophagus in the community that begins with assessing patient risk levels, followed by less-invasive devices and only concludes with an endoscopy where necessary.

The use of less-invasive devices such as a non-endoscopic test where a pill sized device is swallowed to collect oesophageal cells and then retrieved via a string and tested has potential to be applied within a screening strategy, although these devices are currently not available in Australia.

“Currently there is no screening for Barrett’s oesophagus. Its identification is opportunistic, and the test is limited to an endoscopy, which is not only an invasive procedure for patients, but also costly to the health system,” says Dr Bulamu.

“A multi-step strategy is generally more economical compared with going directly to an endoscopy so the acquisition of less-invasive non-endoscopic devices, combined with a risk assessment, is a promising first step in developing an effective and cost-efficient screening approach.”

Senior researcher, says that the study also evaluated serum or blood-based screening tools, but these were found to add substantial costs without significantly improving diagnostic accuracy. For blood-based tools to be viable, they must either achieve significantly higher sensitivity and specificity or be offered at a lower price point.

“If our approach can be translated to clinic, then it could open the opportunity for screening, with patients identified with Barrett’s oesophagus to then be enrolled into regular surveillance, thereby facilitating earlier diagnosis and treatment – including for identifying people with early stage, or at increased risk of developing oesophageal cancer,” says Professor Watson

Whilst the research is promising, researchers acknowledge some limitations and say the results warrant further investigations and analysis considering quality of life benefits and survival resulting from early identification of oesophageal cancer.

The article, ‘ by Tomonori Aoki, David I. Watson and Norma B. Bulamu was published in Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology (2024). DOI 10.1111/jgh.167621

Acknowledgements: Dr. Bulamu is supported by a Cancer Council South Australia Beat Cancer Early Career Research Fellowship.