Rome- Conflict and hunger are inextricably linked to one another. Conflict often leads to severe humanitarian crises, resulting in heightened levels of hunger in specific regions. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) plays a crucial role in addressing these challenges, often operating on the front lines alongside other UN and stakeholder partners to preserve lives and livelihoods.

In an interview with FAO Newsroom, Deputy Director-General Beth Bechdol, who oversees the Organization´s work in emergencies, provided insightful updates on FAO’s efforts in conflict-affected regions, including Gaza, Sudan, and Ukraine, shedding light on the challenges faced and the progress made in addressing food insecurity and promoting stability.

She also discussed FAO’s largest work program in Afghanistan and delved into the impacts of El Niño in Latin America, highlighting the organization’s multifaceted approach to tackling complex issues and fostering resilience in vulnerable communities.

What does FAO’s work entail in an emergency context?

Beth Bechdol: We are in these difficult places to address malnutrition and food insecurity -to deal with unique responses to support the most vulnerable populations. We must also ensure that in these contexts, we are working to rehabilitate agricultural production and agrifood systems. There’s a critical role tied to FAO’s very core mandate.

The balance between immediate emergency assistance and long-term agricultural development is a unique value proposition of our Organization. We often start by providing very important inputs to farmers like seeds, fertilizers, animal vaccines, and animal feed – to help them produce or protect their sources of food. That’s the first line of defense, protection and support in these situations – whether it’s the result of conflict, whether it’s the result of a climate crisis or other disasters.

But FAO’s full technical support in the space of resilience and rehabilitating agrifood systems and agricultural production comes alongside… whether it is seed system delivery, attention to fisheries and aquaculture production to the work that we do on nutrition and food safety, soil health and water management or climate adaptation and mitigation.

These are all critical areas of technical work in resilience-building that FAO is uniquely positioned to provide support for, offering immediate and longer-term solutions together.

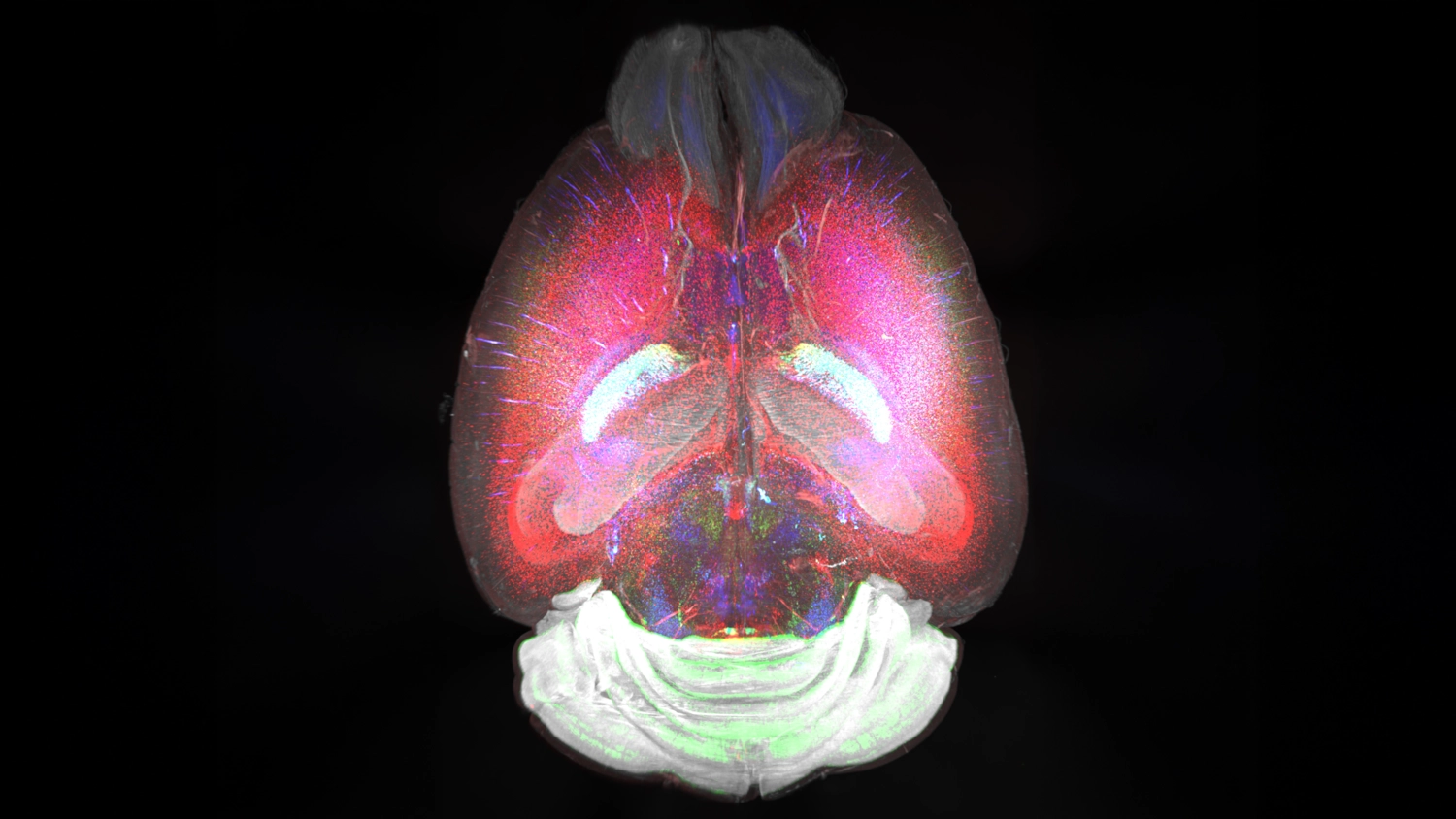

Animal inventories in Gaza are declining. Photo: FAO/Marco Longari

What is the current state of food security and damage to the agrifood sector in Gaza?

There are unprecedented levels of acute food insecurity, hunger, and near famine-like conditions in Gaza. It’s an unprecedented situation that we find ourselves in. We have categories for how we measure acute food insecurity known as the , IPC 3, 4, and 5, which take us from emergency to crisis, to catastrophe. All 2.2 million people in Gaza are in these three categories.

We’ve never seen this before in the analysis and the review that the IPC structure takes on in countries all around the world. Very concerningly, we are seeing more and more people essentially on the brink of and moving into famine-like conditions every day. At this stage, probably about 25% of that 2.2 million are in that top-level IPC five category.

So, with every passing day of not finding a solution to the conflict itself, having a ceasefire or some other end to the hostilities, more and more people are simply going hungry and having less accessibility to food, nutrition, water, and medical services that are so needed there.

We are in a position where we have staff in Palestine, in the West Bank, and are watching all of the circumstances that are unfolding. Sadly, it’s difficult for us to be on the front line to provide any kind of agricultural production support because most of it has been significantly damaged, if not destroyed.

Before the conflict, the people of Gaza had a self-sustaining fruit and vegetable production sector, populated with greenhouses, and there was a robust backyard small-scale livestock production sector. We’ve recognized from our damage assessments that most of these animal inventories, but also the infrastructure that is needed for that kind of specialty crop production is virtually destroyed.

We’re moving now into a space where we are using geospatial technologies, remote sensing, and people on the ground in the best ways we can to try to understand what the rehabilitation reconstruction needs of the people of Gaza will be. If and when we find a time, we can return to that as a response.

We are looking to support as best we can our other U.N. partners. We’re concerned about issues related to sustained funding from many donors to U.N. partners; this is a very sensitive issue. We know that there are certainly politics at work here, but making sure that people can get in to provide this kind of humanitarian support is fundamentally critical today.

We have focused in these last few months on prioritizing potential animal feed deliveries through one or two of the remaining open border crossings where food distribution is taking place. And we’ve encountered some challenges in trying to get those trucks across the border. What we have tried to convey to the Israeli authorities is that providing animal feed, if you have the animals there, is not just sustained livelihood or an economic asset for the families involved. It’s a source of protein, it’s a source of nutrition, it’s a source of milk for children in a family. If you have a few small backyard chickens or two sheep and a few goats, I know that’s considered an economic asset to a family. But I think more importantly, it’s a part of ensuring that there is sustained nutrition.

Sadly, we are realizing with each passing day, though, that animal inventories are declining. So, we’re monitoring this and we’re working closely with the government authorities and those who are trying to coordinate and organize. Right now, the highest priority is making sure that food, water, and medical supplies are the highest prioritized deliveries that are going into Gaza.

Are there any FAO plans to monitor and respond to developments in the West Bank, in Lebanon, in the Red Sea?

We are following very closely all the implications that could be coming. The tensions in the Red Sea, as we’re seeing the attacks that are coming on shipping vessels and in important transport lanes, means that we must be monitoring the safety, security and implications of what happens in global markets and global supply chains when you have shipping lanes close.

We’ve seen some of this before with the war in Ukraine and with the Black Sea corridor, having challenges in bringing shipments to and from key markets.

The ripple effects of the hostilities can move into some of these other places. We have staff and programs in the West Bank and in Lebanon, and we are focusing very much on the implications for global disruptions to either commodity markets or prices.

We’ve come out of so many difficult months of elevated food prices and commodity prices at record levels. We need to make sure that we advocate as best we can to keep the safety and security of these lanes open for everybody.

Sudan is facing a combination of conflicts, economic challenges and even a desert locust outbreak. What is the current food security situation in Sudan?

I would like to start by expressing how disappointing it can be to witness one of the world’s other most difficult and dire situations, regarding food insecurity, not receiving any recognition any longer, and not being covered in mainstream media.

We’ve lost the deserved attention to a conflict where nearly half of the population is in an acute food insecurity situation, with 18 million people struggling. There has been a tremendous loss of life in the Sudan conflict. We have long been present on the ground and have focused extensively on responding to desert locusts and the significant loss of crop production. We are working very closely with farmers and the national government on how to respond and mitigate these challenges, and we continue to monitor the situation.

Despite the conflict and fighting, we still need to ensure that we can provide seed distribution and livestock support to farmers who are striving to maintain viable crops and keep their livestock alive.

FAO Deputy Director-General Bechdol inaugurates the winter wheat seed distribution site in Alishing district, Afghanistan, 2023.

You visited Afghanistan last year. Can you tell us what is the agri-food sector situation over there?

Afghanistan is now FAO’s single largest country program. We have over 400 colleagues there and are present in every one of the 34 provinces in the country. The work we are doing is truly making a difference.

And I think this is another unique story that often doesn’t get presented because given the complexity and history of Afghanistan, there is a sense that many have given up on it. However, we have remained committed and present in the country.

We have stayed regardless of changes to the current de facto authorities, irrespective of the positions taken on women and girls and their positioning in the country. I’m proud to say that even after a decree from the de facto authorities to remove women and girls from public life, FAO has hired even more national Afghan women in our team than we had before that decree. So, there’s a real commitment to serving not only the farmers but the people of Afghanistan.

What we have seen is a gradual reduction in the food insecurity numbers that had been growing over the past several years, with a return to positive trends of reduced numbers of people in food insecure situations.

This doesn’t mean the problem is solved, by any means. We’re now moving through the winter period, which presents its own unique challenges. However, the work that FAO has been doing there with other partners- reaching somewhere around 7 or 8 million farmers last year and intending to reach 10 million this coming year with winter wheat seed, animal vaccines, and other agricultural production inputs- is making a difference.

What has come together is that partners have been there, bringing direct food assistance. Weather and climate conditions have been more favorable to agriculture, and we have moved out of a drought situation into more favorable crop-growing conditions.

And, FAO has been able to bring scaled and on-time delivery of these agricultural production needs, thanks to the generous support from donors like the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank, the EU, the U.S., Japan, and others who have invested significantly in rehabilitating and working on the agriculture sector in Afghanistan.

In a time like we’re in now, where the numbers are dire in so many other places, a model is coming together in Afghanistan with FAO at the centre of it, where we have an opportunity to promote this same approach with donors, partners, and national governments and emphasize the importance of emergency agricultural assistance in making a difference.

What have been the damages and losses in Ukraine’s agricultural sector in the past two years?

The war in Ukraine… it’s hard to believe that we’ve been navigating that for about two years. Before the conflict began and before hostilities broke out, FAO was firmly established and grounded in Ukraine. Despite the recognition of Ukraine as a global agricultural powerhouse before the war, one in four Ukrainians was considered acutely food insecure. There were a significant number of small-scale farmers and people living in rural areas who were still in need of support and assistance. So, it was fortunate that FAO had that kind of presence when the conflict began, serving as a starting point for other UN partners like the World Food Program (WFP), which was not present in Ukraine at the time, to use as a base for operations and collaboration.

But here we are two years later, estimating about $40 billion worth of damage to the Ukrainian agricultural infrastructure. This damage encompasses various aspects, from infrastructure such as grain silos, laboratories, and ports, to farms themselves, including contamination and destruction of land, livestock, and equipment like tractors and other machinery. Additionally, many farmers themselves transitioned into military service, abandoning their land and production. All this underscores the need for careful planning to envision the future of Ukraine’s agricultural sector.

Fortunately, Ukraine boasts an innovative agricultural economy, and we will need to collaborate closely with the Ministry of Agriculture and various agribusiness entities to rebuild this sector when the time comes. We may need to return to basics and focus on rebuilding much of this space.

In Ukraine, we are also working to ensure that crop production can move. About a year ago, we collaborated with the ministry to provide temporary grain storage, successfully offering 6 million tonnes worth of capacity in plastic temporary grain sleeves supported by donors.

Our focus has also been on de-mining agricultural farmland, as per the ministry’s priorities for this year. We are working alongside WFP and another NGO specialized in de-mining to address the significant presence of IEDs and other devices in agricultural lands. Our work involves identifying farmland, knowing boundaries, and collaborating closely with farmers to prioritize this critical task.

Cracked earth during drought. Photo: FAO/Ivo Balderi

With the current El Niño Pattern affecting parts of the world, particularly Latin America, how is the drought impacting food security in the region?

We are closely monitoring the coming El Niño pattern, which often brings prolonged periods of drought and reduced rainfall, especially in Latin America’s Dry Corridor this year.

This is crucial for us to focus on because it’s where a significant aspect of agricultural support lies. Being able to predict and understand drought situations or extended periods of rainfall enables us to assist farmers in better planning for water storage, harvesting, and management.

We can help them identify ways to better prepare for planting crops or caring for their livestock. The Dry Corridor is particularly important due to the significant migration taking place in the region. I had the chance about a year and a half ago to spend a week in Guatemala and witnessed the dryness firsthand, with soils almost incapable of sustaining crops any longer.

This prolonged drought situation leads people to leave their homes and communities, despite their desire to stay and be a part of agriculture to sustain their families and livelihoods. This is where I see a significant opportunity, leveraging FAO’s strategic comparative advantage and technical expertise in land and water management, climate change adaptation, mitigation, and agricultural support. Whether it’s drought-resistant seeds or improved irrigation techniques, these are the solutions needed in this region.

What would be the biggest lesson you can share regarding FAO’s experience in emergencies?

I have one big lesson that we are trying to share with our donors, our partners and our other stakeholders. We have to re-think the entire funding financing model that has long supported responses in an emergency or a crisis setting.

There are 258 million people in IPC 3, 4, and 5 [in crisis, emergency or catastrophic situation of acute food insecurity], and we know that two-thirds or more of those 258 million people are farmers themselves. Let that sink in for just a moment. Two-thirds of the people who are supposed to feed the world are not able to feed themselves. So, something’s broken with this structure.

On the other hand, if we look at how much resourcing is put into these responses, of the global total humanitarian spend to try to address these numerous conflicts, crises, whatever the cause, only 4% of the total funding goes to support emergency agricultural assistance. So, put those two data points as your bookends. Do we have the right model? Are we supporting the right interventions?

And it’s not either-or. It’s not about replacing direct food assistance or commodity assistance in a situation of need with agricultural inputs. It’s putting more complementarity in place between those two as we have been able to do in Afghanistan and to be able to show that when you bring these different types of assistance in a more balanced way – together -, you are better able to address the fundamental root causes of a situation as opposed to simply treating a symptom year over year.

We see conflicts go on for years, and climate disasters that are more protracted like eight- to ten-year droughts, and floods continue to come. So we have to carefully, all of us, find new ways to think about finding the right balance, the right approach, that includes support for farmers, support for pastoralists, support for fishermen and women into these responses. Agriculture is what really can be a part of the longer-term solution to hunger-related issues and to get to the place where we build resilience back into the economies and the lives of those places which are in very difficult situations.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity