An international research project has used gene-editing technology to examine the heat tolerance of Great Barrier Reef coral with the results set to guide efforts in combatting the effects of climate change.

- Scientists have used CRISPR-Cas technology to identify a gene responsible for heat tolerance in a coral on the Great Barrier Reef

The study involving researchers from Stanford University, the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS), and Queensland University of Technology (QUT), used the CRISPR-Cas9 technique to make precise, targeted changes to the genome of coral.

Using this new technique, the research team demonstrated the importance of a particular gene on heat tolerance in the coral Acropora millepora.

Lead author Dr Philip Cleves, Principal Investigator at the Carnegie Institute for Science –Department of Embryology (formerly of Stanford University), developed new genetic methods to study corals and their response to climate change while undertaking postdoctoral research with Professor Pringle at Stanford University and colleagues in Australia.

“We developed an improved CRISPR-Cas9 method that allowed us to test gene function in coral for the first time.” Dr Cleves said.

“As a proof-of-concept, we used CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing to understand the function of a key gene that influences the ability of coral to survive heat.”

AIMS Principal Research Scientist and head of the Reef Recovery, Restoration and Adaptation Team said that the emergence in the past decade of CRISPR-Cas9 provided a powerful tool to study the genes that influence heat and bleaching tolerance in corals.

“Understanding the genetic traits of heat tolerance of corals holds the key to understanding not only how corals will respond to climate change naturally but also balancing the benefits, opportunities and risks of novel management tools such as selective breeding and movement of corals among reefs,” she said.

CRISPR-Cas9 acts like a pair of genetic scissors, allowing scientists to make precise changes to the DNA of an organism which allows them to either turn off a target gene or replace it with another piece of DNA.

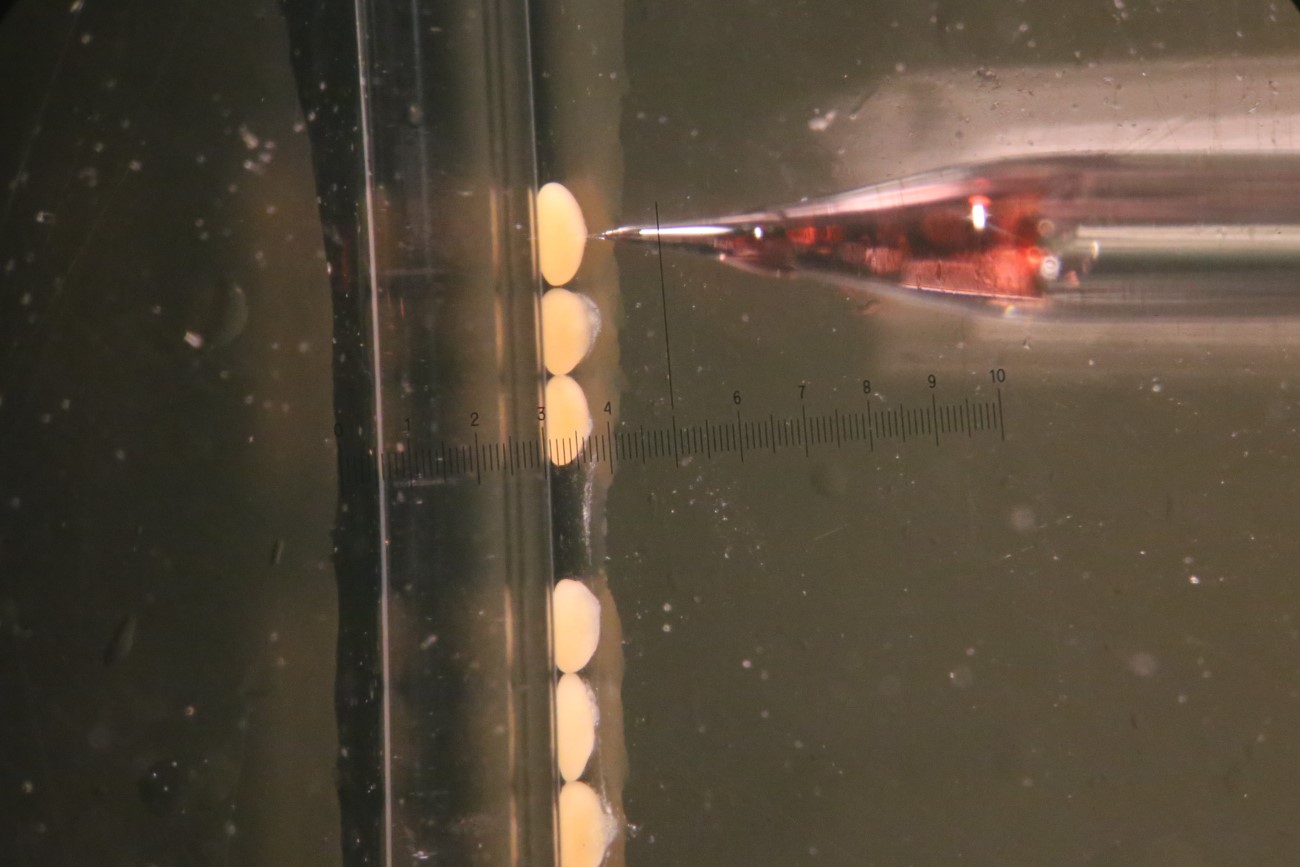

In this study, the researchers used CRISPR-Cas9 to turn off the Heat Shock Transcription Factor 1 gene (HSF1), which plays a crucial role in the heat response in many other organisms.

The modified larvae survived well in water with a temperature of 27 degrees Celsius but died rapidly when the water temperature was increased to 34 degrees. In contrast, the unmodified larvae survived well in the warmer water.

Dr Dimitri Perrin, a chief investigator with the , said the use of CRISPR technology in this study had enabled an increased understanding on the fundamental biology of corals.

“By removing the gene, and then exposing the coral larvae to heat stress, we demonstrated that the modified coral larvae died whereas the unmodified larvae were unharmed under the increased temperature,” Dr Perrin said.

“This result shows the key role HSF1 plays in coral coping with rising temperatures.”

The researchers said they were are excited for this technological advance as it paved the way towards new genetic tools and knowledge for coral which would support their management and conservation in the future.

The scientists who discovered the CRISPR-Cas 9 technique recently received the Nobel Prize for Chemistry.