Depending on the time of the year and where you go in the Amazon, you may see two very different types of “mist”. One is the morning mist, caused by moisture that evaporates from rivers and trees and fills the air with tiny droplets of water. The other one may look like a mist but it is actually smoke coming from forest fires – a dense layer that covers entire regions, sometimes for months. While the former only brings benefits, the latter is harmful to your health and can even be fatal.

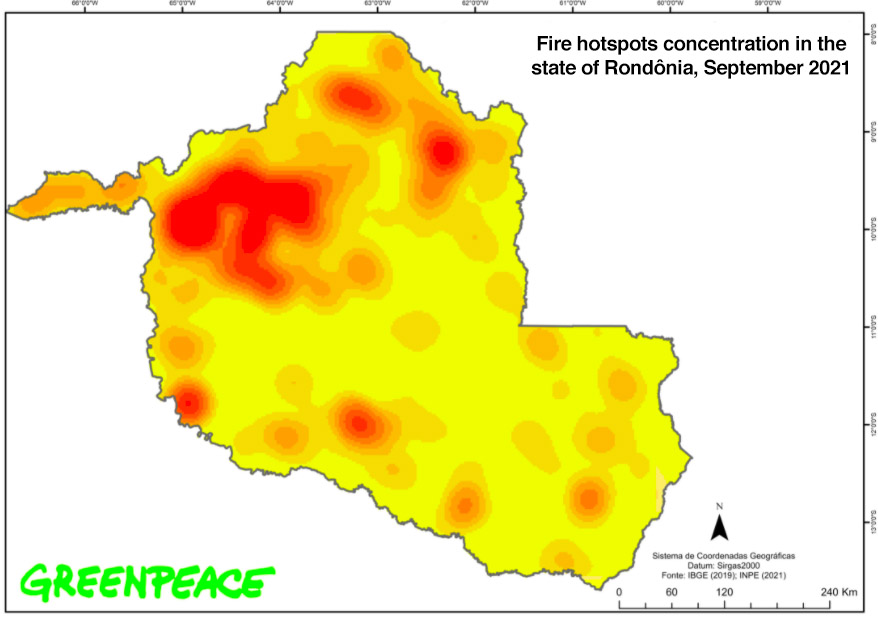

From August 2020 to July 2021, the DETER system of the łÔąĎÍřŐľ Institute for Space Research (INPE) detected alerts for clear-cut deforestation affecting 132,955 hectares in the state of Rondônia. In September of this year, the state capital, Porto Velho, was the municipality with the most hotspots in the entire Amazon.

Every year during the Amazon summer, which runs from July to October, municipalities like Porto Velho experience this direct impact of fires: smoke. Forest fires rarely occur naturally in the Amazon. They are commonly used as part of the deforestation process, either as the last step in clearing the forest or to degrade and weaken large tracts of forest – precisely at the time of the year with less rainfall.

Forest fires directly affect biodiversity and steer Brazil farther away from the international goals to contain the climate crisis. But the first to be affected by them are, without a doubt, the people who live in the region, as the air they breathe becomes toxic. The smoke from fires is filled with tiny particles 2.5 micrometers in diameter or smaller (PM 2.5), which can be carried by the wind and travel through the atmosphere for many kilometers.

These residues, known as particulate matter (PM), can accumulate in the terminal parts of our respiratory system, the alveoli, where the gas exchange of carbon dioxide for oxygen occurs. From there, PM enters the bloodstream, causing immediate and long-term health complications.

Smoke that kills forests and people

The ones most affected by the pollution caused by fires in the Amazon are the elderly and children. “Children, because their immune system is still under development and because they have an anatomically smaller respiratory system,” explained pediatrician Daniel Pires de Carvalho, deputy general director of Cosme e Damião Children’s Hospital, in Porto Velho (RO).

At the Cosme e Damião hospital, a reference in the treatment of children in the state, an increase in hospital visits and hospitalizations during the forest fire season is now a typical annual phenomenon for which the health care system must always be prepared. According to Daniel, this year, the volume of hospital visits by children due to respiratory problems in July was 50% higher than that recorded in January, when air quality was better, with higher humidity and no smoke from the fires.

The most common symptoms caused by interaction with particulate matter are burning in the throat and nostrils, pain when breathing, headaches, and persistent cough. But the effects can be even more devastating for patients with co-existing medical conditions, such as hypertension, asthma, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

“If the child or adult feels fine and does not show any deterioration in their health, such as difficulty breathing or shortness of breath, then that’s manageable. But if there is evidence of a complication, it is important to look for health care right away to get a diagnosis and appropriate treatment,” warned the pediatrician.

In August 2020, Human Rights Watch, in partnership with the Institute for Health Policy Studies (IEPS – Instituto de Estudos para Políticas de Saúde) and the Amazon Environmental Research Institute (IPAM – Instituto de Pesquisa Ambiental da Amazônia), released, where they analyze the impact of fires on the health of Amazonian populations in 2019.

According to the document, 2,195 people were hospitalized in 2019 in municipalities located in the Amazon biome due to respiratory diseases attributable to increased pollution caused by deforestation-related fires. The number of hospitalizations increases substantially in the Amazon summer, when forest fires become more common: more than half of the admissions in that year occurred between August and November. It is estimated that the total public costs associated with hospitalizations due to deforestation-related fires made up BRL 5.64 million (USD 1.4 million).

“Whenever air quality is worsened due to forest fires, the demand for health facilities increases and healthcare costs increase as well due to the procedures that must be performed. This economic issue affects families too – medications must be bought, transportation must be paid for, and so on. So it’s a loss not only for the health sector, but for society as a whole,” said Arlete Baldez, epidemiologist and technical manager of the Rondônia State Surveillance and Health Agency (AGEVISA – Agência Estadual de Vigilância e Saúde do estado de Rondônia).

AGEVISA has been monitoring air quality and respiratory diseases in the state’s municipalities through a program that was started to monitor the progress of respiratory diseases related to COVID-19 and anticipate possible impacts on the health care system. The agency compares air quality data with the occurrence of diseases that become more common in the presence of specific environmental influences, such as pollution. “We monitor and alert these municipalities to prepare themselves when there are many forest fires and lots of smoke and particulate matter, and it is expected that asthma and bronchitis cases will increase. In fact, we deal more with the consequences of this problem than with attempting to find a proper solution to it.”

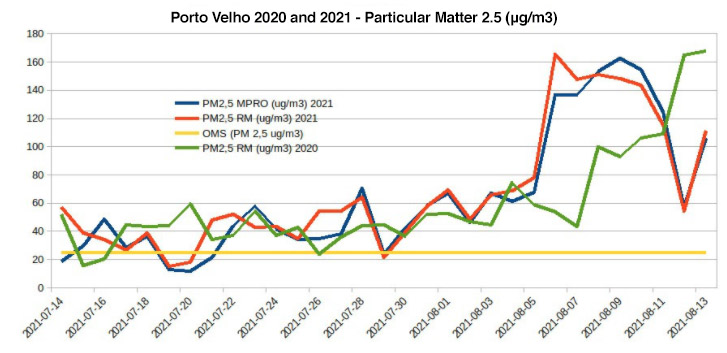

According to the , exposure to pollution causes 7 million premature deaths in the world every year and reduces the population’s life expectancy. In September this year, the organization revised the Global Guidelines for Air Quality. For particulate matter, daily average levels now cannot exceed 25 μg/m3.

But in July, Porto Velho reached PM levels much higher than the average stipulated by WHO. On August 10 this year, the concentration of particulate matter in the city reached 160 μg/m3. Of 30 days analyzed by the sensor from the Roraima State Prosecution Service, only five days had air quality within WHO’s recommendations.

Chain Reaction: Smoke conducive to COVID-19 complications

It is not possible to measure the impact of smoke on the population of the Amazon precisely since most available data only consider hospitalizations, disregarding a whole set of affected people who do not seek medical care. Side effects and long-term effects are yet another matter.

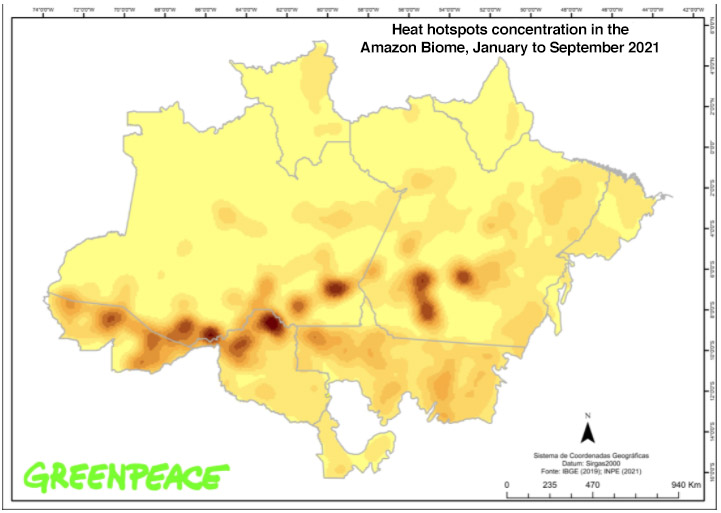

A survey carried out by InfoAmazônia project points out that, in 2020, in the 5 Amazon states which had the most forest fires last year (Amazonas, Acre, Rondônia, Mato Grosso, and Pará). According to the study, Rondônia was one of the most affected states. In September, the state’s worst month of the pandemic in 2020, the chance of being admitted to hospital due to COVID-19 complications in Rondônia was 66% higher than in places where air quality was within acceptable limits.

This greater vulnerability occurs due to the impairment of the respiratory system caused by smoke, as explained by Deusilene Vieira, a public health researcher at the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz) in Rondônia, where a microbiology team analyzes the interaction between smoke and the proliferation of viruses and bacteria. “These viruses are present throughout the year, but once there is a change in context, with more smoke and greater confinement, the viruses presence increases. This happens with other viruses as well, like seasonal influenza, and coronaviruses in general, not only SARS CoV-2,” she explained.

But what we see today is just the tip of the iceberg. Particulate matter can continue acting for many years inside the human body. Chronic exposure to these particles.

The impacts outside the region

“Smoke, or particulate matter, does not only harm those close to where it is emitted. It travels many kilometers, reaching people at great distances from the location of the forest fire. It travels very, very far from where it starts,” emphasized Arlete Baldez. In fact, events in which particulate matter is taken to distant regions as fires advance in the Amazon, Pantanal, and Cerrado, affecting air quality far beyond the limits of each biome.

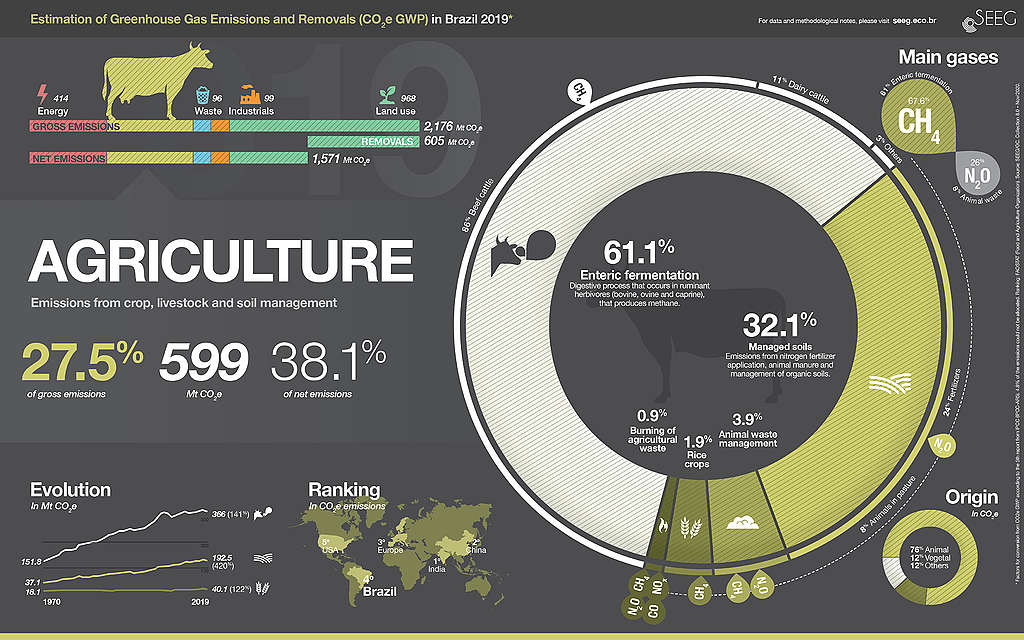

Forest fires emit greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, aggravating the ongoing climate crisis. The existing data on emissions from forests fires is underestimated, but fire is one of the stages of land-use change due to deforestation, and according to data from the Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Removal Estimating System (SEEG), land-use change accounts for 44% of Brazil’s total emissions.

“We are currently experiencing a health crisis, a climate crisis, and a biodiversity crisis. An accumulation of challenges that are interconnected,” said Cristiane Mazzetti from Greenpeace’s Amazon campaigner. “Deforesting and burning forests sickens local populations and generates incalculable losses to the plant and animal biodiversity of these regions, besides contributing to an increase in the frequency and intensity of climatic extremes, such as droughts and floods, which are already affecting thousands of people throughout the world. The Brazilian government, as well as those who are directly or indirectly related to the destruction of the Amazon, must take responsibility and commit to protecting the forest. After all, protecting the forest is also a matter of public health.”

Rosana Villar is a journalist at Greenpeace Brazil.