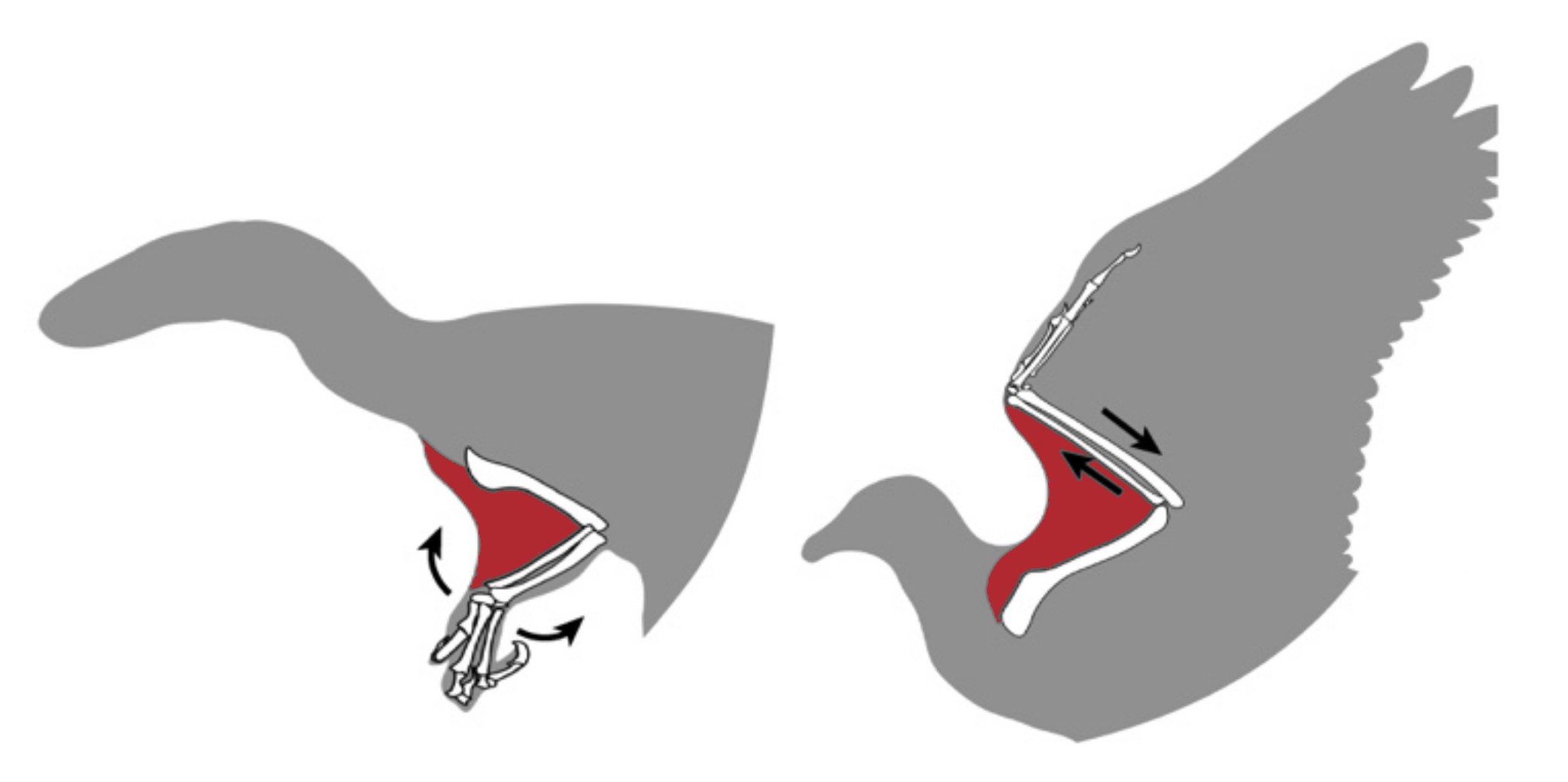

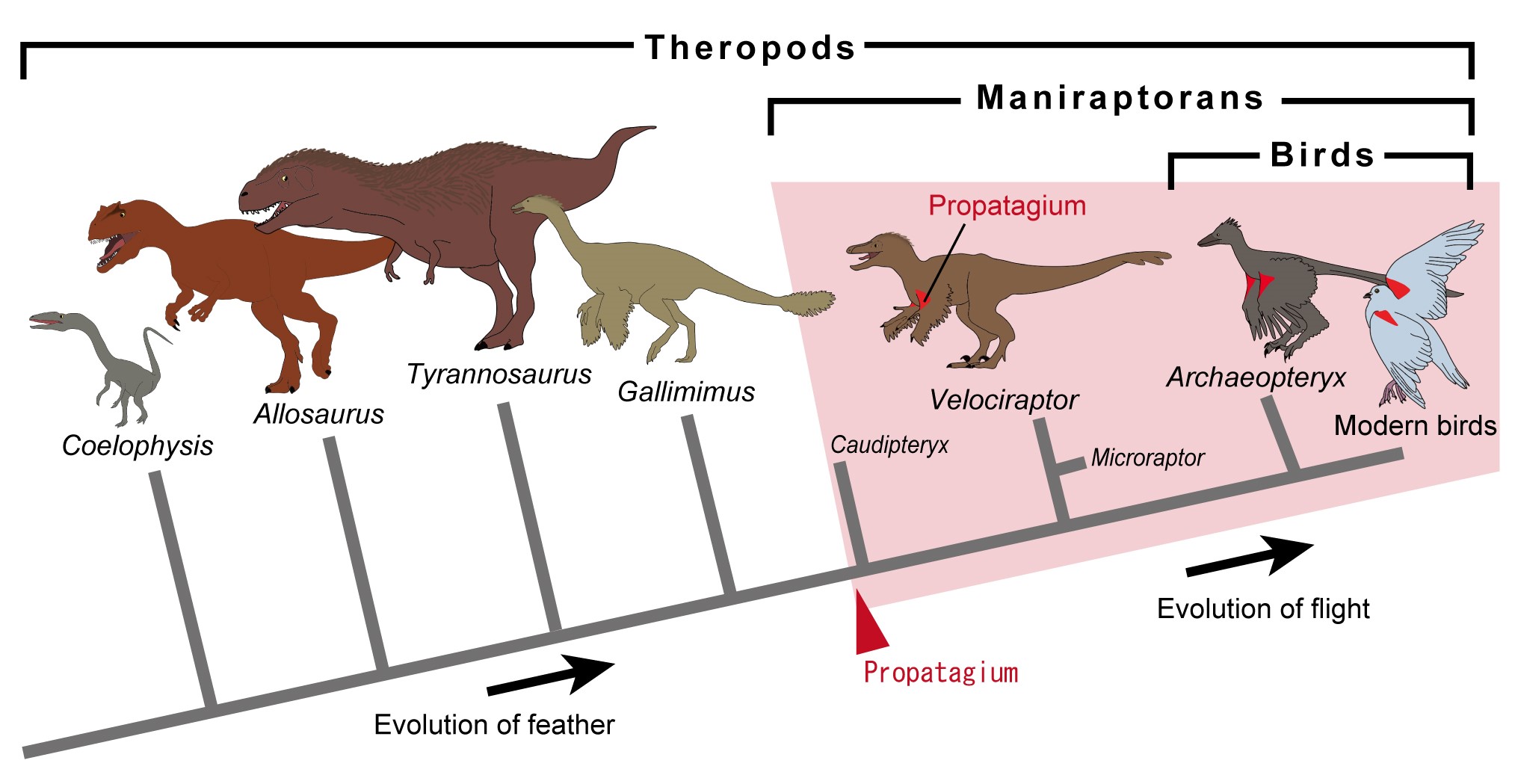

Propatagium old and new. This comparison between theropod arms and bird wings shows how researchers think the propatagium allowed for different kinds of movement as the former evolved over millions of years into the latter. ©2023 Yurika Uno and Tatsuya Hirasawa CC-BY

Modern birds capable of flight all have a specialized wing structure called the propatagium without which they could not fly. The evolutionary origin of this structure has remained a mystery, but new research suggests it evolved in nonavian dinosaurs. The finding comes from statistical analyses of arm joints preserved in fossils and helps fill some gaps in knowledge about the origin of bird flight.

For a long time now, we have known modern birds evolved from certain lineages of dinosaurs that lived millions of years ago. This has led researchers to look to dinosaurs to explain some of the features unique to birds, for example, feathers, bone structure and so on. But there’s something special about the wings of birds in particular that piqued the interest of researchers at the University of Tokyo’s Department of Earth and Planetary Science.

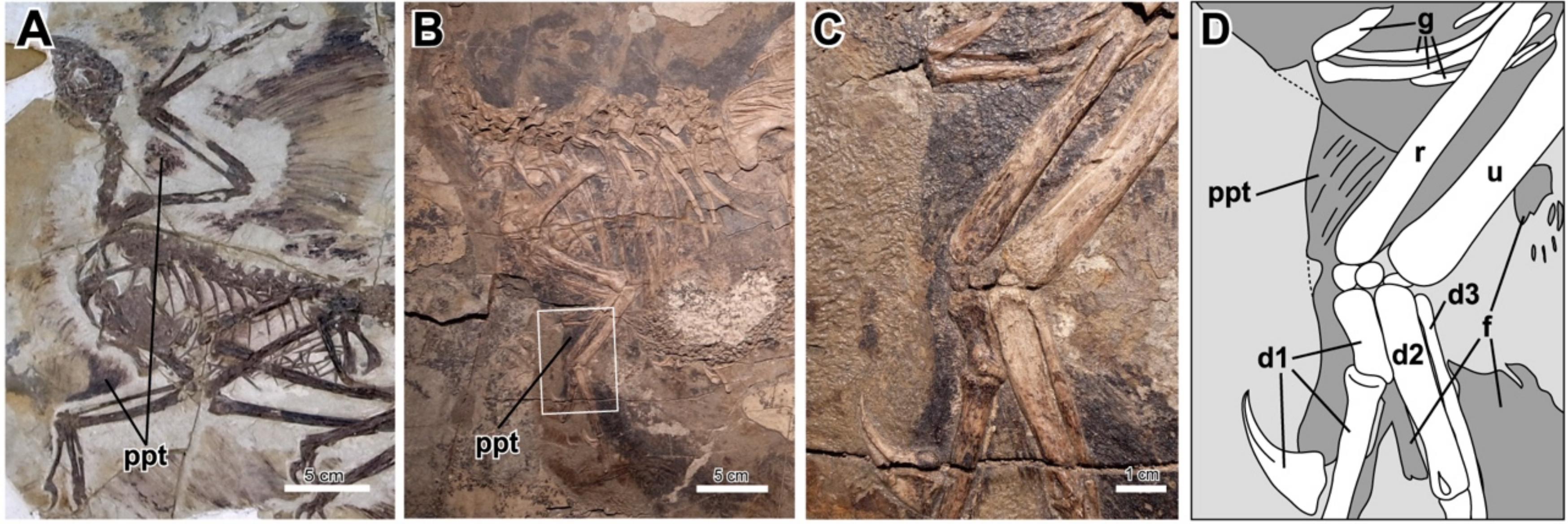

Soft tissue preservation. Although soft tissue such as that found in the propatagium don’t fossilize well, there are some exceedingly rare, well-preserved examples such as these. The propatagium is labeled ppt in image D. ©2023 Yurika Uno and Tatsuya Hirasawa CC-BY

“At the leading edge of a bird’s wing is a structure called the propatagium, which contains a muscle connecting the shoulder and wrist that helps the wing flapping and makes bird flight possible,” said Associate Professor Tatsuya Hirasawa. “It’s not found in other vertebrates, and it’s also found to have disappeared or lost its function in flightless birds, one of the reasons we know it’s essential for flight. So, in order to understand how flight evolved in birds, we must know how the propatagium evolved. This is what prompted us to explore some distant ancestors of modern birds, theropod dinosaurs.”

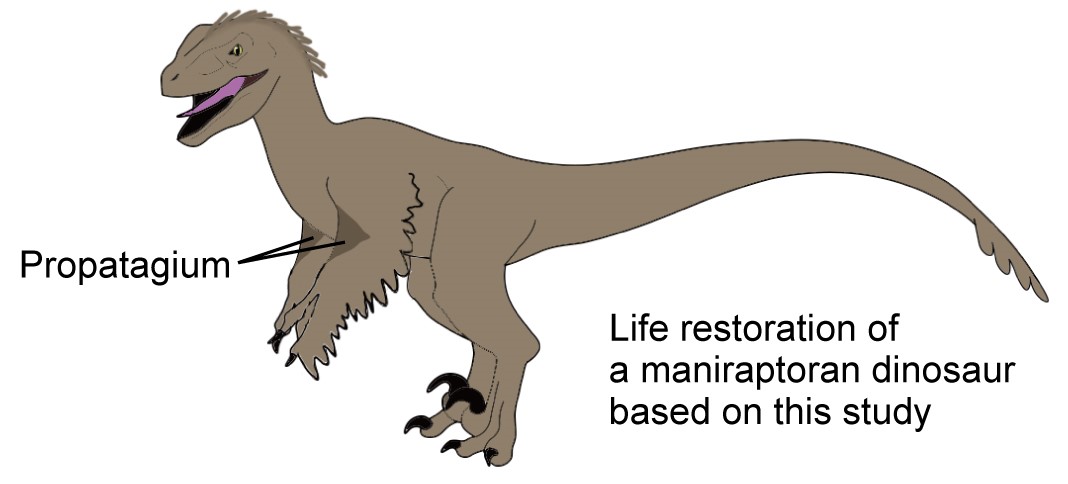

Updated dinosaur design. A more accurate version of a typical maniraptoran dinosaur, a common species to feature in popular media. ©2023 Yurika Uno and Tatsuya Hirasawa CC-BY

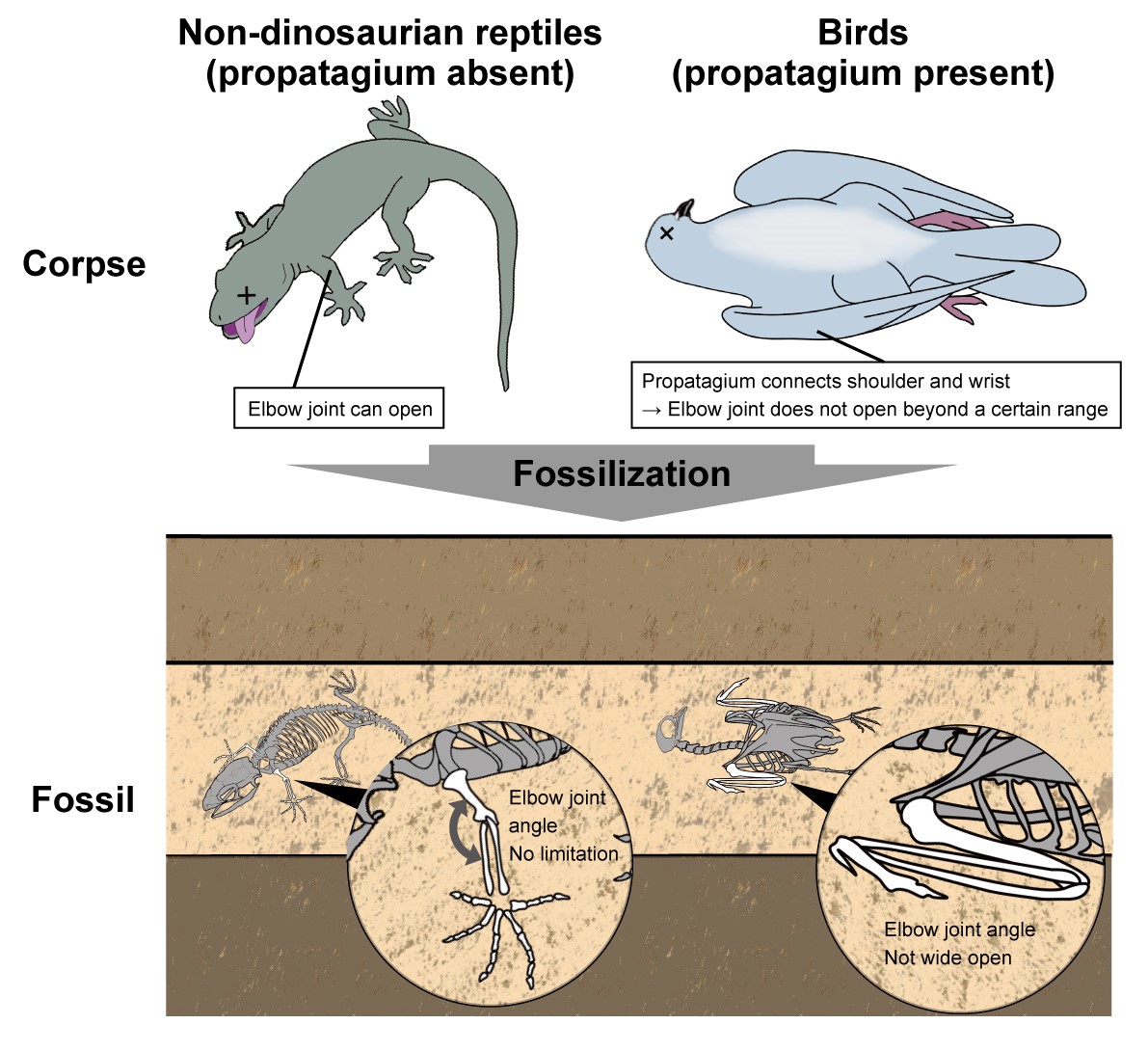

Theropod dinosaurs, such as Tyrannosaurus rex and Velociraptor, had arms not wings. If the scientists could find evidence of an early example of the propatagium in these dinosaurs, it would help explain how the modern avian branch of the tree of life transitioned from arms to wings. However, it’s not so simple, as the propatagium is made up of soft tissues which do not fossilize well, if at all, so direct evidence might not be possible to find. Instead, the researchers had to find an indirect way to identify the presence or lack of a propatagium in a specimen.

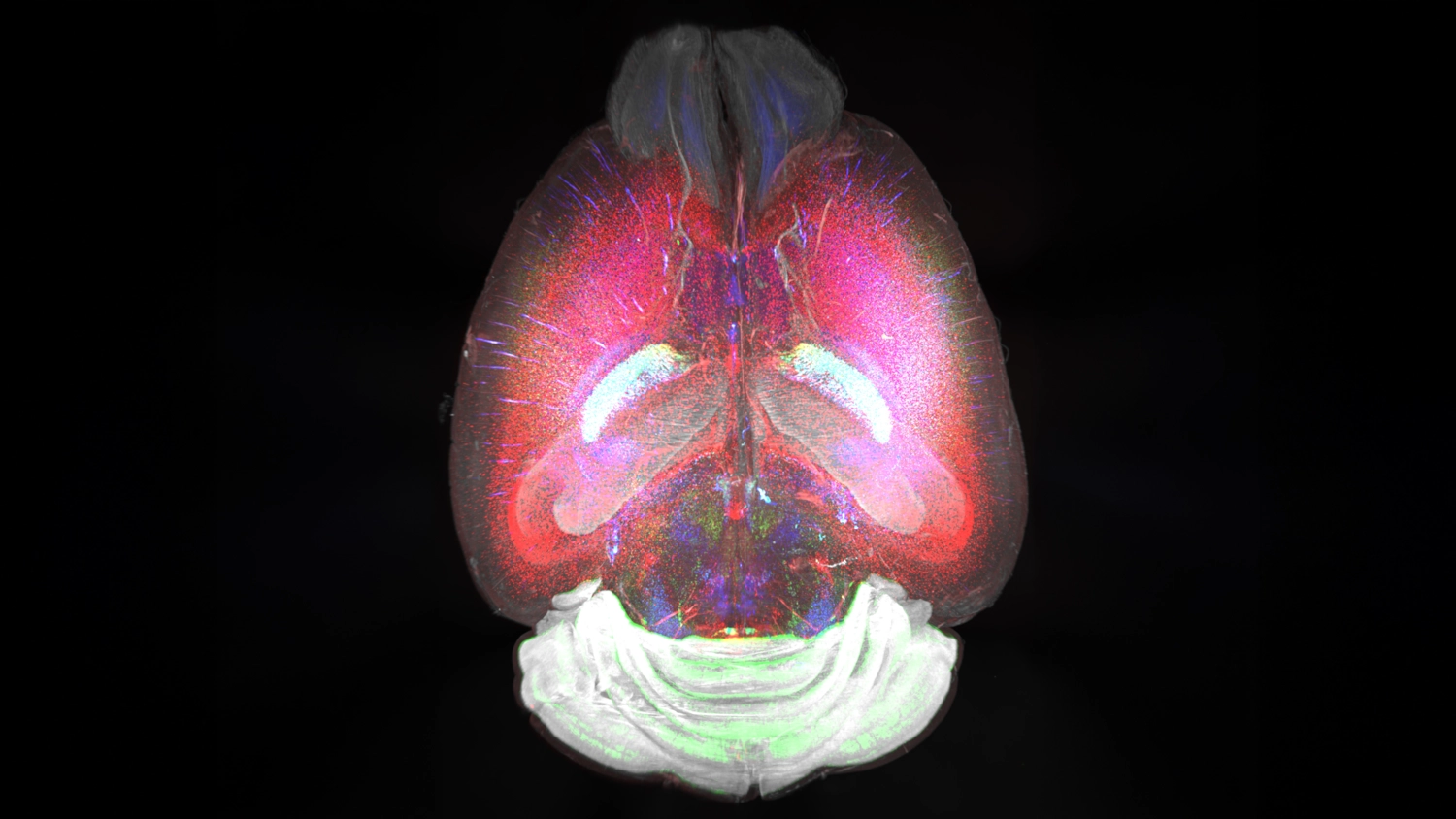

Wing evolution in birds. A branch of the tree of life that includes the time when the propatagium, vital to flight in future birds, came about. ©2023 Yurika Uno and Tatsuya Hirasawa CC-BY

“The solution we came up with to assess the presence of a propatagium was to collect data about the angles of joints along the arm, or wing, of a dinosaur or bird,” said Yurika Uno, a graduate student at Hirasawa’s lab. “In modern birds, the wings cannot fully extend due to the propatagium, constraining the range of angles possible between connecting sections. If we could find a similarly specific set of angles between joints in dinosaur specimens, we can be fairly sure they too possessed a propatagium. And through quantitative analyses of the fossilized postures of birds and nondinosaurs, we found the telltale ranges of joint angles we hoped to.”

Why joint angles matter. The way arm joints are articulated in fossils gives away the presence or absence of the propatagium. ©2023 Yurika Uno and Tatsuya Hirasawa CC-BY

Based on this clue, the team found that the propatagium likely evolved in a group of dinosaurs known as the maniraptoran theropods, including the famous Velociraptor. This was backed up when the researchers identified the propatagium in preserved soft tissue fossils, including those of the feathered oviraptorosaurian Caudipteryx and winged dromaeosaurian Microraptor. All the specimens they found it in existed prior to the evolution of flight in that lineage.

This research means it’s now known when the propatagium came into being, and it leads researchers on to the next question of how it came to be. Why these particular theropod species needed such a structure to better adapt to their environment might be a harder question to answer. The team has already begun exploring possible connections between the fossil evidence and embryonic development of modern vertebrates to see if that will shed any light on it. The team also thinks some theropods might have evolved the propatagium not because of any pressure to learn to fly, as their forelimbs were made for grasping objects and not for flying.

“Dinosaurs portrayed in popular media are becoming more and more accurate,” said Hirasawa. “At least now we get to see features like feathers, but I hope we can see an even more up-to-date representation soon where theropods have their propatagium too.”