Petty Officer Henry Kindler recalls the sad ending to Australia’s first attempt to establish a submarine service.

“I stood by the conning tower to warn the captain, to make sure that AE2 would sink fast. He just got on deck when she took her final dive. For a few seconds, I could see her moving through the water like a big, wounded fish, gradually disappearing from sight. I felt sorry to see AE2 come to such an end but she had died fighting.”

It had begun with two boats – the AE1 and AE2 built by Vickers Armstrong in England and commissioned into the Royal Australian Navy in 1914, just ahead of the First World War.

Initially the submarines were deployed in the Pacific – a disastrous experience for AE1, which vanished off New Britain just three months into the war.

AE2, however, lived to fight another day, arriving at 2.30am on April 25 in the Dardanelles, just in time to support Anzac troops as they landed at Anzac Cove, which it did with some distinction.

It was the first submarine to enter the Sea of Marmara and successfully travel the length of Dardanelles Strait, after a British and French boat had been sunk in the attempt, and sunk a Turkish gunboat in the process.

AE2’s mission was to “run amok” and torpedo transports bringing Ottoman reinforcements to the Gallipoli battlefields. She operated for five days before mechanical faults forced her to the surface, where she was damaged on April 30, 1915 by the torpedo boat Sultanhisar and was eventually scuttled by her crew, all of whom were captured. The submarine then lay unseen until 1998 when she was discovered, intact.

Near 100 years later, the boat lying in 72 metres of water in the Sea of Marmara, was the only neglected Gallipoli battlefield until a diverse team of Australian, Turkish and US submariners, scientists, divers and historians and Defence Scientists came together to record, preserve and tell the story of the wreck.

The ‘Silent Anzac’ project, which came to fruition in July 2014, relied heavily on technology developed by the Defence Science and Technology Organisation (DSTO), as it was then called.

The team was led by DSTO’s Dr Roger Neill, the expedition’s science director, who led the automation and unmanned maritime systems unit at DSTO. He described the wreck as “an underwater time capsule that has not been opened since 1915”.

The challenges he faced were formidable, including custom designing and building a high-definition underwater camera that would fit through a 100mm opening at the main hatch and lighting to show the way. They even needed to work out a wrapping for the cabling to protect against the aggressive conger eels that live in the area.

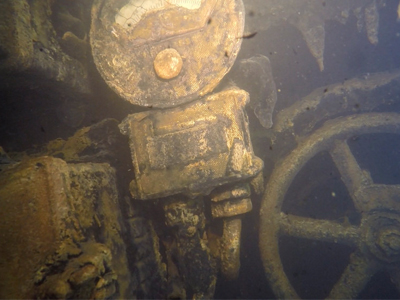

An underwater image of the AE2 wreckage.

After filming, the Defence scientists installed a cathode protection system around the wreck to control corrosion, as well as a marker buoy to protect it from shipping traffic, anchors, and fishing nets.

To protect the AE2 against further corrosion, the DSTO scientists worked with Dr Ian MacLeod of the Western Australian Museum, a specialist in preserving shipwreck sites.

The ingenious cathode protection system involved placing one-tonne zinc arrays around the boat, which will become an anode, linked to a zinc plate on the side of the wreck. Copper cables link the two.

As zinc is more reactive than iron, it gives off its electrons more readily, so the electrons take the easy path and the zinc corrodes in place of the iron. Zinc electrons flow into the iron hull and the iron electrons stay where they are, preserving the ship.

A drop camera shines a light into the Ae2 prior to its preservation work.

The project leader, retired Rear Admiral Peter Briggs paid tribute to the clarity of the images sent back by DSTO’s roving camera and the details that could be identified from the 3D model Dr Neill spent years perfecting.

“The submarine is in amazingly good condition, original paint, signalman’s sand shoes still stowed in the flag locker in the conning tower along with the flags and what we believe was the battle ensign used by Lieutenant Commander, Henry ‘Dacre’ Stoker, DSO, 99 years ago,” he said at the time.

One of the most significant discoveries of the exercise was a portable wireless telegraph pole and antenna wire, the existence of which had long been the subject of discussion of military historians. It is most likely that it was this telegraph which transmitted the message to Army headquarters that AE2 had torpedoed an Ottoman gunboat at Çanakkale,

The Turkish Government continues to ensure maintenance of the buoy laid over the AE2 in a gesture of friendship between old enemies.

The AE2 submarine memorial plaque located at the Maritime Museum Fremantle.

As we continue to mark the 115th anniversary of Defence science in Australia, we will see the important contributions the scientists and engineers of the Defence Science and Technology Group have made to Australia’s later, more successful submarine ventures.