Asking him about the worst pain he feels, causes a slightly awkward moment for .

“Well, I go surfing with my kid all the time but I’m terrible and she’s good,” he says in his quietly Canadian accent. “And my back kills afterwards. I mean, I’d give it a three. But it’s not what a real pain patient feels.”

Allowing that Neely is a pain researcher, having found his way there via immunology, he is aware of the profound ordeal pain can be. It seems so elemental, but it’s surprisingly complex, even subtle. Think that the eye can deliver a picture with colour, texture, shine, sharpness and softness. The pain system, with specialised sensors throughout the body, can deliver something just as detailed but composed of sensation.

“Long-term pain changes the whole thing,” says Neely from a bright and airy staff area in the where he and his team do their work. “That pain from your peripheral injury or your back, changes your spinal cord and it changes your brain.”

When these biological changes lock in for some still unknown reason, chronic pain is the result, persisting long after the original source of the pain has righted itself. This ongoing, sometimes life-destroying, pain affects one in five Australians, both young and old, and costs the nation nearly $140 billion a year in treatment and lost productivity. The focus of Neely’s work is how to isolate those biological changes and change them back.

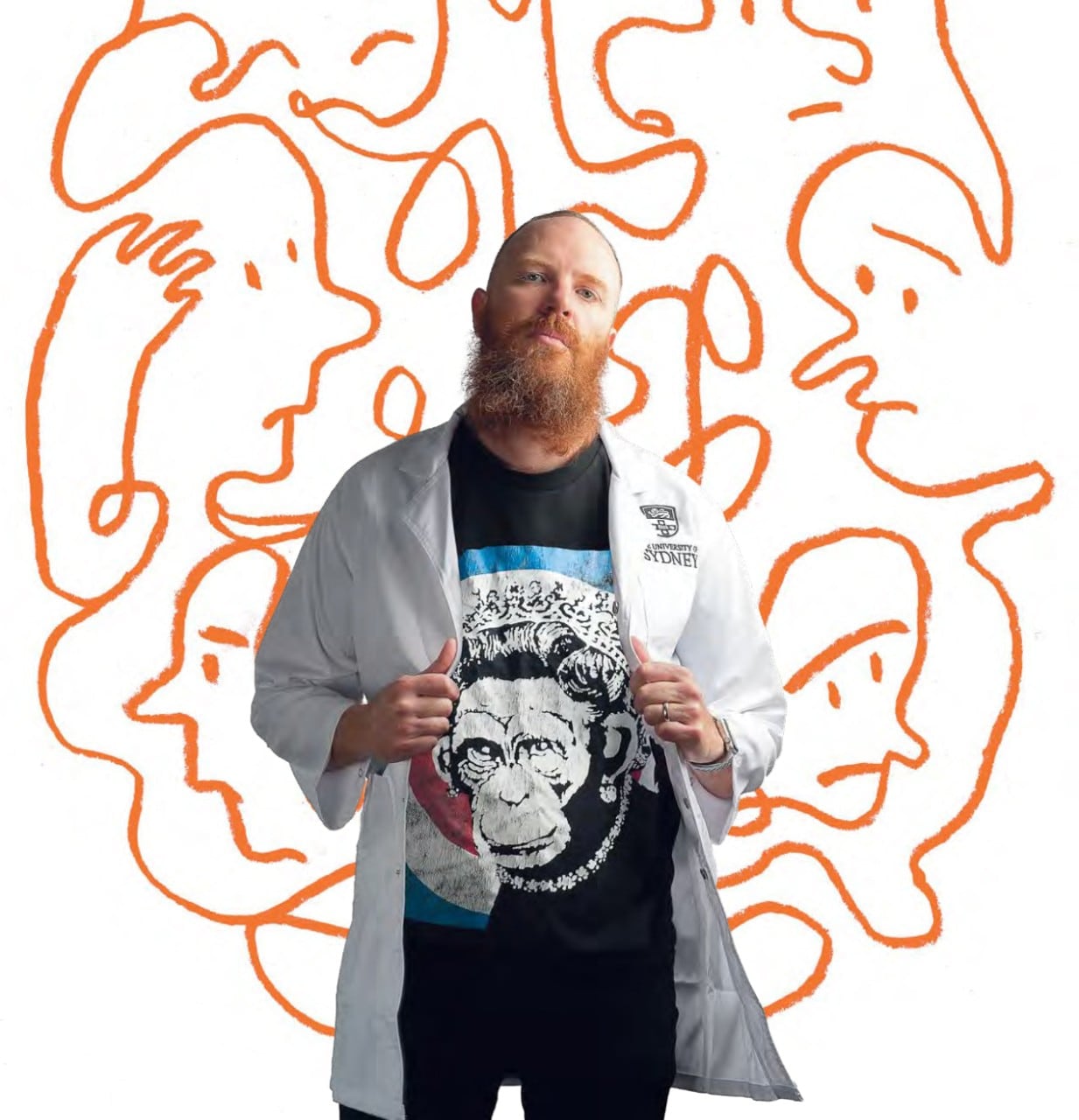

Professor Greg Neely works out of the Charles Perkins Centre.

Though the main focus is on pain research, what happens in Neely’s lab is wide-ranging with new technologies opening up new ideas. “Once we master the technology, team members in different areas say to me, ‘Oh hey, why don’t we try using it for this?’ I’d say that 90% of what we’re doing right now has come from discussions like that.

“For me, the two key questions for a new research project are; is it technically feasible and is it interesting?”

The pain-brain connection

An early pain therapy success, using pluripotent stem cells derived from blood, has been encouraging. Allowing that stem cells can shapeshift into a range of cells needed by the body, Neely’s team caused them to shift into a form of neuron known to be pain-killing. The neurons were then transplanted into the spinal cords of mice at the location where a specific pain signal was known to originate.

Long-term pain changes the whole thing. That pain from your peripheral injury or your back, changes your spinal cord and it changes your brain.

The pain not only stopped, but the results were long term and without side effects. Another benefit is how site-specific the treatment is, meaning there is no apparent overflow that effects other parts of the body in the way that opioids cause drowsiness, breathing problems and indeed, addiction. This is because the technique doesn’t really treat pain, it restores normal functioning.

There is one more transformative possibility with this technique. When people present at a hospital with an injury that might end in chronic pain, as 10% to 20% of injuries do, the stem cell therapy, or drugs achieving the same effect, could be applied as a preventative part of the initial treatment.

Human trials of the stem cell therapy are expected after more exploratory work is done. And there is plenty more for Neely’s team to explore, especially around the genetics of pain.

The role of genetics and jellyfish

“Forty to sixty percent of your experience of pain is genetic. And out of 22,000 genes in the human genome, I’d say maybe 5,000 genes are involved in chronic pain,” says Neely. “I mean, there could be 400 genes related to heat pain alone.”

Another aspect of the team’s work was through it’s insight into what is considered one of the most excruciating pains you can experience; a box jellyfish sting, which so intense it can cause vomiting, cramping, blackouts and erratic behaviour.

The traditional treatment for jellyfish stings is vinegar. Neely’s insight came from somewhere else completely. The entry point was genetic using CRISPR technology. CRISPR stands for “clusters of regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats”, which for most people isn’t all that enlightening, but it is, in effect, like scissors for cutting strands of DNA into its component parts.

CRISPR is already used to correct genetic defects, treat disease and improve crops. Neely’s team used it to cut a human genome to pieces to make a sort of gene stew, to which was added box jellyfish venom. The human genes that survived were examined and an insight emerged: four of the top ten genes required for the venom to do its work, were part of a pathway that makes cholesterol in human cells.

“Obviously, there’s been a lot of study on cholesterol over the last 30 years, so there are already drugs available that target steps in cholesterol regulation,” says Neely. “We found these drugs could completely block the ability of the box jellyfish venom to kill human cells in the lab.”

As Neely’s team, which includes seven post-doctoral researchers across a range of specialities, teases out insights that might one day end chronic pain, there has been an update of how to help people currently living with the condition.

The Pain Management Research Institute

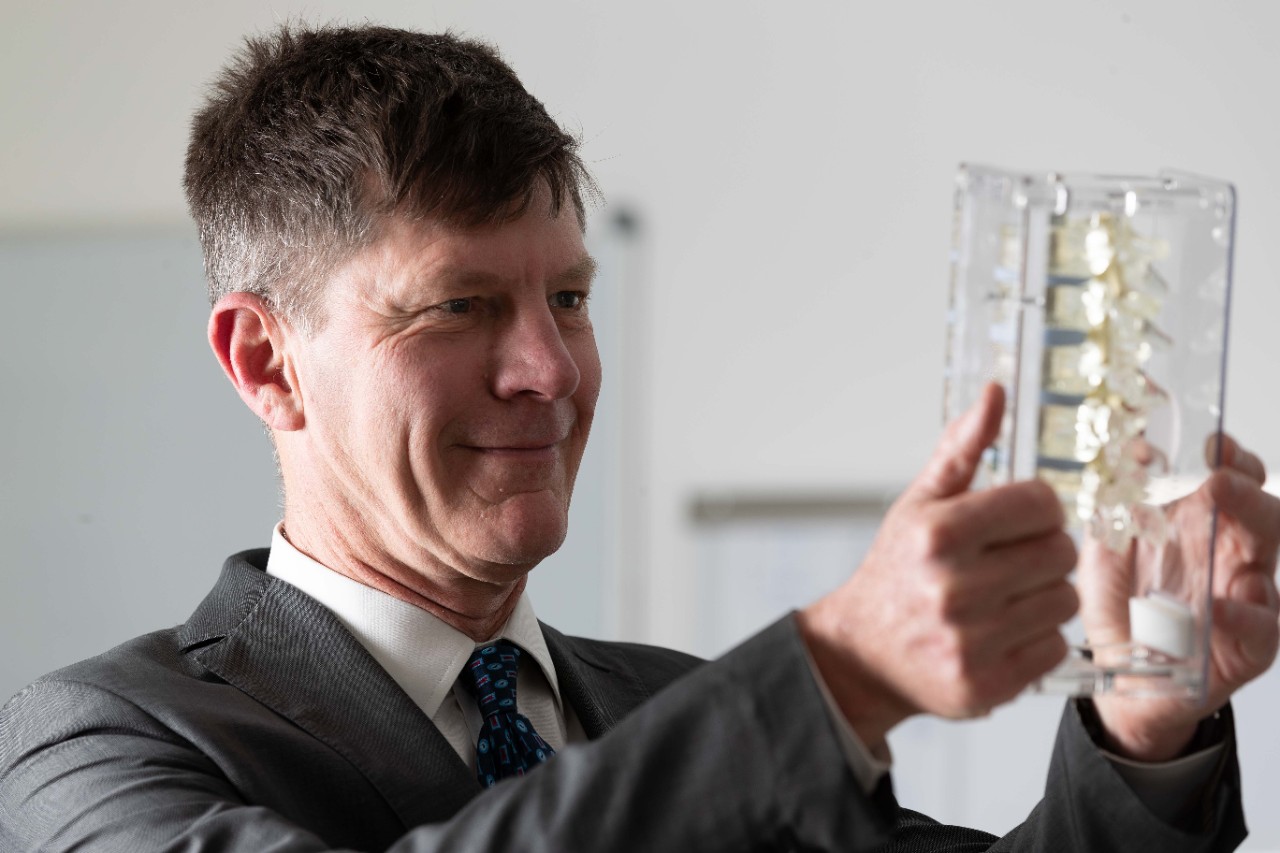

The University’s is a multidisciplinary unit reflecting the fact that pain itself can be discussed in medical, psychological, even philosophical terms. (MBBS ’81, MM(ClinEpid) ’05) is the Director of the PMRI and Head of the Discipline of Pain Medicine in the Sydney Medical School, and he has a particular interest in giving people with chronic pain the tools they need to function without using opioids.

Professor Paul Glare at the Pain Management Research Institute.

“Opioids are good for acute pain. With chronic pain they only work short to medium term,” he says. “But after about six months, you become tolerant and have to take bigger doses. Then there’s the growing risk of accidental overdose, even accidental death.”

For many people though, opioids seem like the only way to numb the pain that constantly attacks them. But do they in fact, numb the pain?

“Most people who come off the long term use of opioids realise that the drugs weren’t doing that much,” says Glare. “They’d already stopped working, so the pain without them is often no worse. In fact, the drugs were just messing with their heads. Still it’s a huge psychological step to let the drugs go.”

Gently spoken and with a great sense of compassion for the people he works to help, Glare started his career in palliative care which took him into the area of cancer pain, then pain more generally. Because it’s difficult to tell people battling chronic pain that there is no satisfactory pharmaceutical answer at this time, the PMRI has a large and active pain education unit.

The Unit offers a that is also conferred as a Masters of Science for non-medical graduates. It also runs cognitive behavioural therapy classes teaching strategies for rising above the pain.

“The classes are challenging,” says Glare. “But many people who learn the self-management techniques can reduce or even stop their opioid use. It’s about them not being afraid of their pain anymore.”

It’s the nature of chronic pain that the injury it’s warning you about, sometimes very loudly, isn’t actually there. This can be seen in a person’s posture as they sit and walk in a way that protects that non-injury. By gently confronting the pain, the person can eventually reclaim their normal posture and walk more confidently. Through that, they feel stronger within themselves and more in control of their pain.

The PMRI is now looking at digital support resources for people dealing with pain, “We’re developing an SMS based text messaging service and a more sophisticated chat-bot tool, to help people get over the hump of opioid tapering,” says Glare. “It’s new in the pain world.”

AN END TO PAIN

To find out more or to help research into understanding pain please call Lachlan Cahill on +61 2 8627 8818 or email

Written by George Dodd. Illustrated by Oslo Davis. Photography by Stefanie Zingsheim and Louise M Cooper.