As celebrated author testifies, books are the best place to bury your head when life gets too hard. For cancer sufferers, this could be especially true.

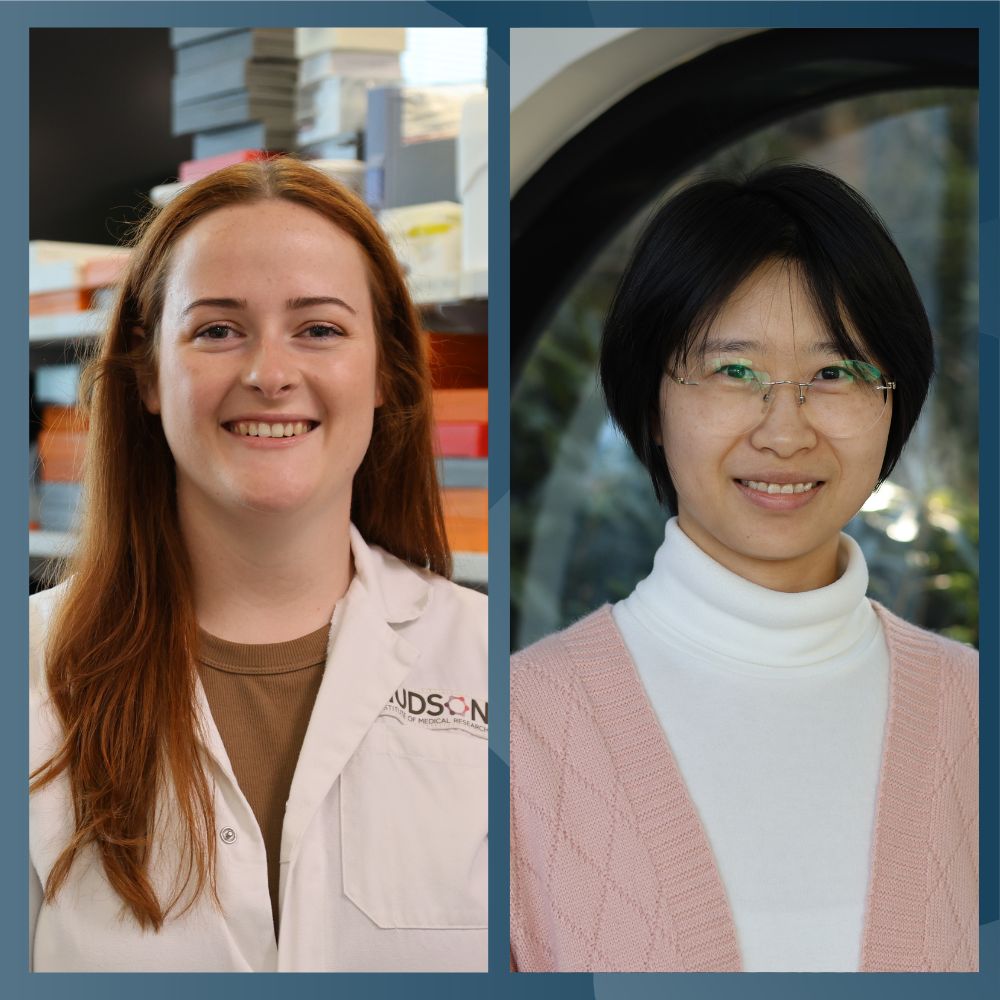

University of South Australia (UniSA) PhD candidate Elizabeth Wells is hoping to validate this claim in a new study exploring the benefits of (being read to) for cancer patients.

The qualified librarian has witnessed firsthand the impact of cancer-induced brain fog on people undergoing chemotherapy, losing the ability to read and focus, sometimes for years into remission.

“It happened with my mother, who had a particularly aggressive form of cancer, but I also noticed it with many of my library patrons diagnosed with cancer,” Wells said. “They found it increasingly hard to read because chemotherapy mostly affects the frontal lobe of the brain, involved in attention and memory.”

Wells introduced her chemotherapy-affected library patrons to large print and audio books, hoping these would fill the gap, but further investigation revealed the potential benefits of delivering bibliotherapy as a read-aloud program.

“There is strong evidence from the UK, where bibliotherapy is common practice, that being read to helps improve mental health, grief, and even chronic pain. In the cancer context I’m looking at, listening involves a different part of the brain that is generally not affected by chemotherapy.”

The evidence-based research is scarce, however; something that Wells hopes to address with her own study, recruiting 40 cancer patients from metropolitan, regional and rural areas of the state to undergo a six week bibliotherapy trial.

“We are looking for volunteers at different stages of treatment – people who have just been diagnosed with cancer and are about to start treatment, those during it, and people who have completed their treatment in the past 12 months.

“Cancer fog can affect people going though all types of cancer treatments, so recruitment to the study is not limited to those undergoing chemotherapy, and also not limited to those with acknowledged cancer fog,” Wells says.

The participants don’t have to be regular readers either; just open to someone reading a work of fiction to them, 30-40 minutes each week for six weeks, on a subject or author of their choice.

“There is something to be said for losing yourself in a book and escaping reality for a while, particularly for people who are facing some very tough battles, including painful health conditions.”

While chemotherapy is thought to be the main culprit for cancer fog – particularly for breast cancer patients – existing studies show that cognitive impairment can also occur when a tumour first appears.

Wells will monitor cancer patients’ stress and anxiety at the beginning of the six-week project and then measure it at the end. Family members will also be interviewed where available.

Reading sessions can be conducted in person, at their home, in a park or library, or over Zoom, although the latter is the least preferred option because of the known benefits of social connection, achieved by face-to-face sessions.

“My personal goal is to establish reading programs in cancer centres. I would love to see that,” she says.

For more information, visit