Ireland needs to prepare itself to meet rising pressures on public finances from an ageing population and significant external risks such as new EU-UK trade barriers post Brexit. Another important development could be future changes to the international tax rules, according to a new OECD report.

The latest projects Irish GDP growth at 6.2% in 2019, then at still solid rates of 3.6% in 2020 and 3.3% in 2021. Yet the risks to these forecasts are significant and Ireland’s high public debt and fragilities in the banking system could exacerbate any economic shock. The coming years will also be marked by rising health and pension costs, as the population ages, and a possible end to several years of tax windfalls.

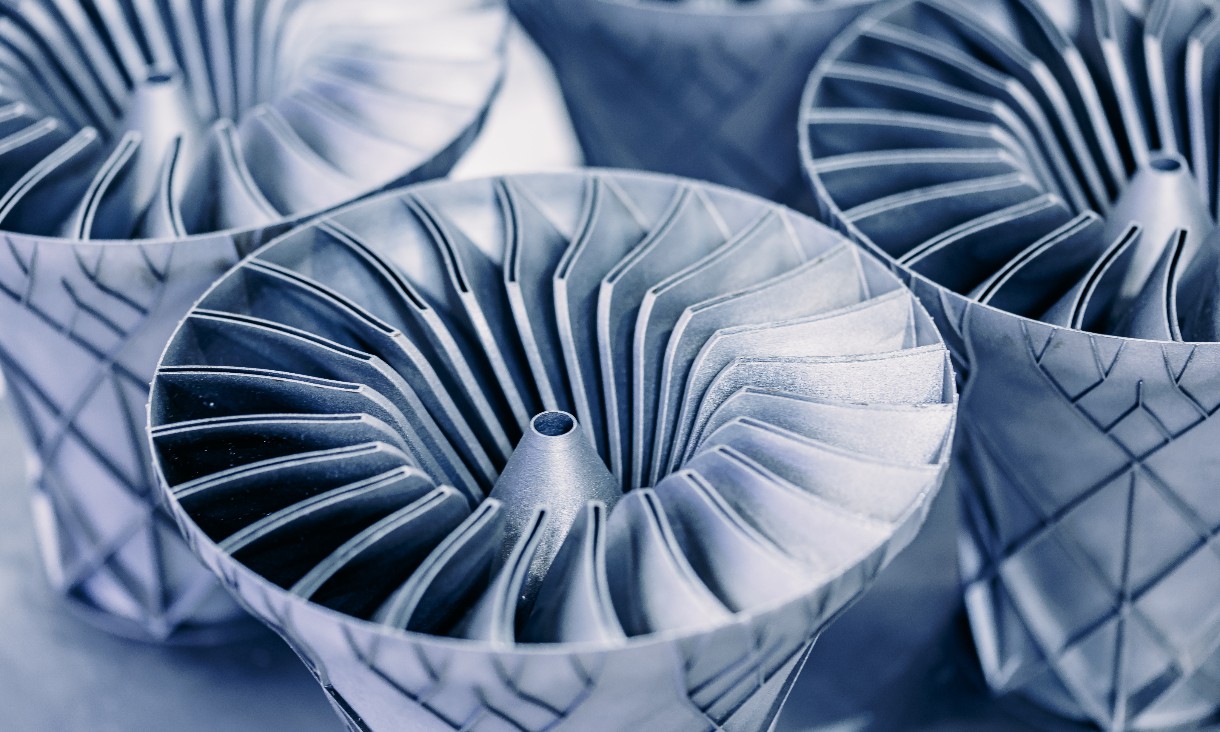

The Survey recommends taking concrete steps to improve public spending efficiency and find new sources of revenue. It is also vital to maintain Ireland’s attractiveness as an investment hub for multinationals, for example through addressing skills shortages in the workforce, lowering barriers to competition such as complex licensing procedures, and ensuring good transport infrastructure and affordable housing in Dublin. Improving skills and the use of new technologies could also help to narrow the productivity gap between Irish and foreign firms. “Ireland’s open economy has helped it emerge stronger from the crisis, yet the country is very exposed to external factors. Fiscal prudence will be vital with health and pension costs set to rise just as the economy faces disruption from Brexit and a potential drop in corporate tax receipts,” said OECD Chief Economist Laurence Boone. “This is a crucial time for Ireland and the focus for the incoming government should be to keep the economy on a solid track.” | > |

Ireland has enjoyed windfall tax receipts as an investment hub for multinationals, but a planned overhaul of global tax rules is expected to lower related tax receipts by changing how and where corporate tax is paid. In recent years, Ireland has partly used one-off tax receipts to fund cost overruns in health and welfare. Future windfalls should go towards paying off debt or into the country’s strategic ‘rainy day’ investment fund, and cost overruns should be reined in through better budget planning.

Health spending per person is already high in Ireland. Ageing will push it higher, while reducing revenues from labour taxes. Simulations suggest that public health and pension costs could rise by 1.5% of GDP annually by 2030 and by 6.5% of GDP by 2060. Basic pension benefits have risen much faster than inflation in recent years; indexing future increases to consumer prices would produce budgetary savings.

New revenue sources could focus on property and consumption taxes, which are less distortive for economic activity than income tax. Property values should be regularly reassessed for calculating local property taxes – today’s are based on 2013 values – and VAT should be streamlined from five rates to three. Low-income households should be cushioned from any adverse impacts. Separately, efforts to increase housing supply should continue as a way to curb soaring property prices.

Ireland stands particularly exposed to Brexit risks. The United Kingdom is an important trading partner, particularly in agriculture and food, and a vital land bridge for the majority of Irish exports that are bound for Europe. Exports of machinery, equipment, chemicals and tourism to the UK have stagnated or fallen since the 2016 UK referendum on EU membership, and any re-imposition of customs and border controls would hurt flows of goods to EU destinations.

Such risks make it even more important that Ireland reap as much benefit as it can from the digital economy. Irish businesses have tended to embrace new technologies well, the special digital chapter shows, but the impact on firm-level productivity growth has been modest.

See an Overview of the Survey with key findings at . (This link can be included in media articles.)