The source is located in a region with a high rate of star births

Fast radio flashes still pose something of an enigma to astronomers. Although they only emit for milliseconds at a time, hundreds have been observed in the sky. Only four such Fast Radio Bursts (FRB) have been precisely located so far. Now astronomer have traced the source of a newly discovered FRB to a nearby spiral galaxy similar to our own Milky Way, a galaxy half a billion light-years from Earth, making it the closest FRB to Earth ever localized. The burst called FRB 180916.J0158+65 was observed by a group of eight radio telescopes, including the 100-meter Effelsberg telescope.

One of the greatest mysteries in astronomy right now is the origin of short, dramatic bursts of radio light seen across the universe, known as Fast Radio Bursts or FRBs. Although they last for only a thousandth of a second, there are now hundreds of records of these enigmatic sources. However, from these records, the precise location is known for just four FRBs – they are said to be ‘localised’.

In 2016, one of these four sources was observed to repeat, with bursts originating from the same region in the sky in a non-predictable way. This resulted in researchers drawing distinctions between FRBs where only a single burst of light was observed (‘non-repeating’) and those where multiple bursts of light were observed (‘repeating’).

“The multiple flashes that we witnessed in the first repeating FRB arose from very particular and extreme conditions inside a very tiny (dwarf) galaxy”, says Benito Marcote, from the Joint Institute for VLBI ERIC, the lead author of the current study. “This discovery represented the first piece of the puzzle but it also raised more questions than it solved, such as whether there was a fundamental difference between repeating and non-repeating FRBs. Now, we have localised a second repeating FRB, which challenges our previous ideas on what the source of these bursts could be.”

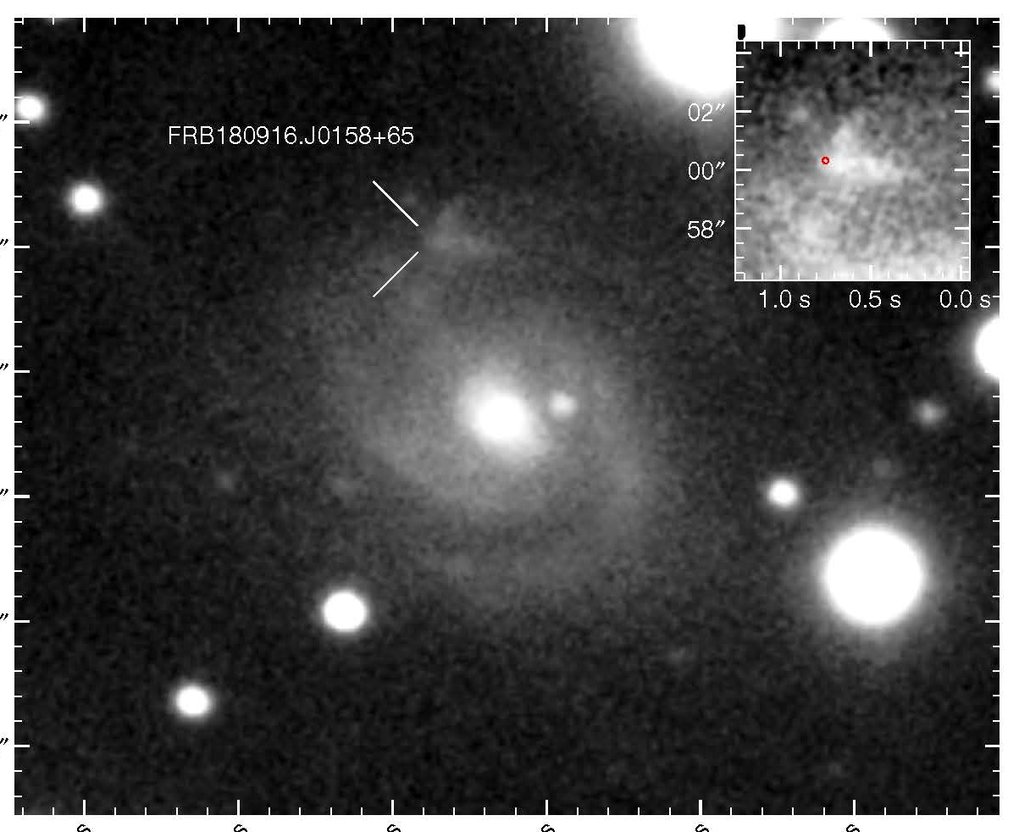

On 19th June 2019, eight telescopes from the European VLBI Network (EVN) simultaneously observed a radio source known as FRB 180916.J0158+65. This source was originally discovered in 2018 by the CHIME telescope in Canada, which enabled the team to conduct a very high resolution observation with the EVN in the direction of FRB 180916.J0158+65. During five hours of observations the researchers detected four bursts, each lasting for less than two thousandths of a second. The resolution reached through the combination of the telescopes across the globe, using a technique known as Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI), meant that the bursts could be precisely localised to a region of approximately only seven light years across. This localisation is comparable to an individual on Earth being able to distinguish a person on the Moon.

The Effelsberg 100-m radio telescope of the Max Planck institute for Radio Astronomy (MPIfR) played a crucial role in these observations in two ways. With the flexible instruments at this telescope one could record data amenable to rapid identification of radio bursts and a form of data suitable for high resolution radio imaging. Secondly the large collecting area of the telescope makes it an indispensable element in the coordinated interferometric observations of weak sources like this FRB.

With the precise position of the radio source the team was able to conduct observations with one of the world’s largest optical telescopes, the 8-m Gemini North on Mauna Kea in Hawaii. Examining the environment around the source revealed that the bursts originated from a spiral galaxy named SDSS J015800.28+654253.0, located half a billion light years from Earth. The bursts come from a region of that galaxy where star formation is prominent.

“The found location is radically different from the previously located repeating FRB, but also different from all previously studied FRBs”, explains Kenzie Nimmo, PhD student at the University of Amsterdam. “The differences between repeating and non-repeating fast radio bursts are thus less clear and we think that these events may not be linked to a particular type of galaxy or environment. It may be that FRBs are produced in a large zoo of locations across the Universe and just require some specific conditions to be visible.”

“With the characterisation of this source, the argument against against pulsar-like emission as origin for repeating FRBs is gaining strength”, says Ramesh Karuppusamy of the MPIfR, a co-author of the study. “We are at the verge of more such localisations brought about by the upcoming newer telescopes. These will finally allow us to establish the true nature of these sources”, he adds.

While the current study casts doubt on previous assumptions, this FRB is the closest to Earth ever localised, allowing astronomers to study these events in unparalleled detail.

“We hope that continued studies will unveil the conditions that result in the production of these mysterious flashes. Our aim is to precisely localize more FRBs and, ultimately, understand their origin”, concludes Jason Hessels, corresponding author on the study, from the Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy (ASTRON) and the University of Amsterdam.