Following the Nicholson’s closure on 28 February, its collection will occupy a key position within the new museum, currently being constructed on the Camperdown campus and opening in August 2020.

The Macleay and University Art collections will also be displayed in the Chau Chak Wing Museum.

“This is an historic moment for one of the University’s beloved institutions as once again it relocates to allow future generations to enjoy its wonderful diversity of precious objects. Their incalculable contribution to the education and enjoyment of hundreds of thousands of people since the Nicholson’s foundation will continue,” said David Ellis, Director Sydney University Museums.

Renowned as the largest collection of antiquities in the Southern Hemisphere, of artistic and archaeological significance from Egypt, Greece, Italy, Cyprus, Ireland, the United Kingdom and the Middle East, from the Neolithic to Medieval periods.

“While a respected museum, the Nicholson could never exhibit more than a fraction of its treasures at any one time,” David Ellis said.

“The move to a dedicated space at the Chau Chak Wing Museum will allow much more of this world-class collection to be appreciated.”

New state-of-the-art exhibition and teaching facilities in the will enable unparalleled opportunities for students and community to engage with the University collections.

Early history of the Nicholson

Originally located in the front section of the Quadrangle building – and guarded for decades by a gigantic monument of the Egyptian goddess Hathor, the museum was known colloquially as the Nicholsonian (before being formally named the Nicholson Museum in 1904) and opened to the public in 1860.

From 1909, the collection was gradually moved into three rooms located beneath the original Fisher Library, now MacLaurin Hall, where it currently resides.

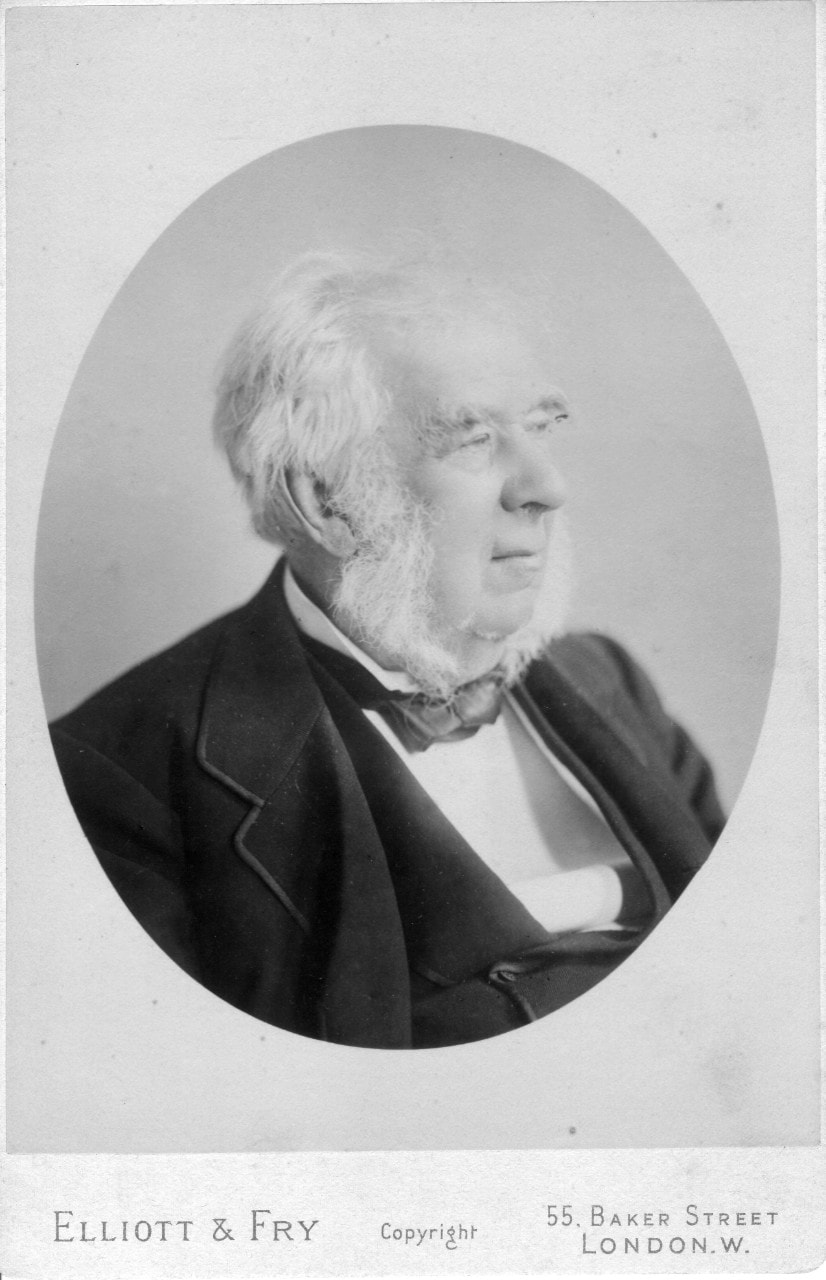

Sir Charles Nicholson

The major force behind the creation of the museum, Victorian polymath Sir Charles Nicholson was the University’s first Vice Provost during the 1850s. He was determined the University should have a museum. After a failed attempt in 1852 to have the Australian Museum moved to the campus, he then travelled to Italy and Egypt to acquire the foundations of the collection.

Etruscan, Greek, Roman and Egyptian antiquities featured among Nicholson’s original donation of more than 3000 objects including mummies, coffins and sculptures such as the massive bust of Horemheb, the last pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty of Egypt.

The breadth of the material donated by Nicholson reflected his own diverse interests and his forward-thinking focus demonstrated by his acquisition of objects suited to a teaching museum.

That teaching focus continues to this day and object-based learning will be a major feature of the Chau Chak Wing Museum.

“We will have the opportunity to share the collection with students and visitors of all ages through dedicated hands-on experiences”, said Dr Craig Barker, Manager of Education and Public Programs within Sydney University Museums.

One of the University’s greatest benefactors, Sir Charles Nicholson continued to add artefacts to the collection for decades after returning to the United Kingdom in 1862, as well as art works, which became the basis of the , and books, to what would become .

Post Second World War

Nicholson Musem in the 1930s. Credit: University of Sydney.

Under the stewardship of a succession of dynamic curators, the Nicholson collection continued to expand, building on relationships with newly formed organisations conducting scientific archaeological excavations, such as the Egyptian Exploration Society.

The museum gained objects from around the Mediterranean during this period including artefacts of great significance such as the Jericho skull and an Egyptian papyrus fragment of book 5 of the Iliad, (c.200 AD). The Jericho skull (c.9000 BC) is ‘decorated’ with plaster and paint to create human features and is one of the earliest examples of portraiture.

The museum also forged a relationship with the local Sydney community, with the foundation of the society in 1945. The Friends have assisted with the acquisition of more than 50 objects and funded visits of international scholars to Australia.

Nicholson in the 21st century

Since 2005 the Nicholson collection has been mostly digitised and curators have continued their commitment to making it accessible to a wider audience through publications and temporary exhibitions. The playful LEGO model exhibitions with recreations of the Colosseum, Acropolis and Pompeii have been hugely popular.

“In the 25 years that I have known the Nicholson Museum, it has gone from a static display to one with dynamic exhibitions, comparing and contrasting ancient cultures with each other and our own contemporary world,” said Dr Craig Barker, Manager of Education and Public Programs.

“The closing exhibition is a good example -it explores the connections between Nicholson objects and objects in museums around the world and the way the latest research enables new answers.”

New technologies have been used to investigate objects in the collection including , bone analysis, radiocarbon dating, DNA analysis and vibrational spectroscopy of the Egyptian mummies and coffins.

Just as it did in the early 20th century, in recent years the Nicholson Museum has engaged directly with archaeological fieldwork, museum staff directing the Paphos Theatre Archaeological Project in Cyprus and the Khirbet Ghozlan Excavation Project in Jordan, and supporting researchers and students working at sites such as Pella in Jordan and Zagora in Greece.

This text is based on an article on the Nicholson’s history by .

Featured image: Nicholson Museum. Credit: University of Sydney.