Water demand due to population growth is outstripping improvements in Australians’ efficiency of household water use, according to new research commissioned by Sustainable Population Australia (SPA) in a report titled Big thirsty Australia: how population growth threatens our water security and sustainability.

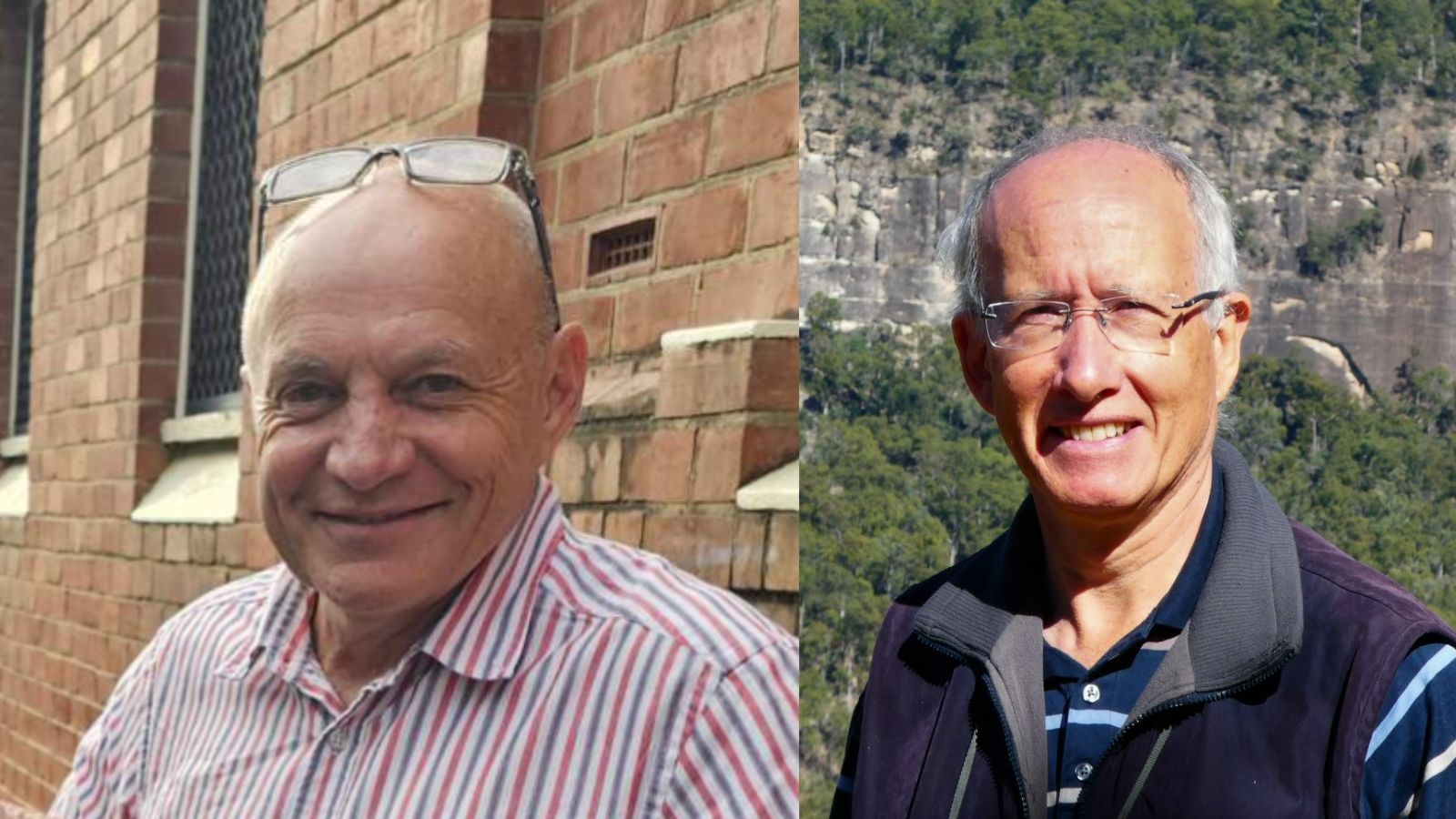

“Since 2010-11, per person water use in the household sector has remained relatively stable. It is becoming harder to find new efficiencies; the low-hanging fruit such as public educational campaigns, water efficiency labelling for appliances and reduced garden size, have been picked,” says Dr Peter Cook, one of the authors of the report.

The report finds the demand pressures from population growth are coming at the same time as climate change is drying capital city water catchments in what is already the driest inhabited continent. Together these factors are making Australia’s cities more vulnerable to extended droughts, the report says.

“Since the early 2000s, water demand in many Australian cities has exceeded what can be supplied reliably by conventional means, namely rainfall and groundwater,” says another of the report authors, Dr Jonathan Sobels.

The report finds that water demand projections by mainland urban water authorities anticipate further population growth will require adding anywhere from 850 gigalitres (GL) to over 1450 GL to annual water supply to capital cities over the next several decades. (A gigalitre is equal to one billion litres of water, which would fill a cube 100 metres in each direction, or 400 Olympic swimming pools.) For purposes of comparison, 1450 GL is around the total volume of water currently supplied each year for Sydney, Melbourne and Perth combined.

“State governments and water utilities are turning to desalination of seawater to augment water supply to meet population growth. Yet desalination is hugely expensive. Per litre of water, desalination is at least 2.5 times the cost of rain-fed dam water, which means much higher water bills for households and businesses,” Dr Sobels says.

“Desalination is also energy intensive; electrical energy costs are around 41% of the operating costs for these plants. Even if renewable energy is used, it will not be displacing fossil fuels used in other sectors, so it does not improve carbon footprint or sustainability. There are also risks with the siting of these coastal desalination plants, due to the likelihood of sea level rise because of climate change,” Dr Sobels adds.