Key Points

Uranium can be extracted from seawater simply and effectively using a new material

Adding neodymium to layered double hydroxides (LDHs) improved their ability to capture uranium selectively

Multiple techniques at ANSTO clarified the octahedral coordination environment, oxidation state and adsorption mechanism

An Australian-led international research team, including a core group of ANSTO scientists, has found that doping a promising material provides a simple, effective method capable of extracting uranium from seawater.

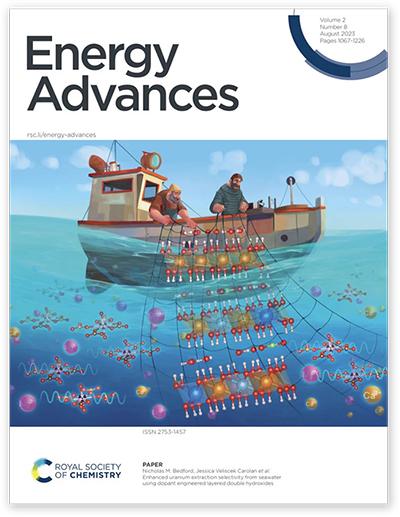

The published in Energy Advances and featured on the cover, could help in designing new materials that are highly selective for uranium, efficient, and cost-effective.

Uranium is a highly valued mineral used as a fuel source in nuclear reactors around the world.

“There’s a lot of uranium in the oceans, more than a thousand times more than what is found in the ground, but it’s really diluted, so it’s very difficult to extract. The main challenge is that other substances in seawater, salt and minerals, such as iron and calcium, are present in much higher amounts than uranium,” explained lead scientist Dr Jessica Veliscek Carolan, who supervised co-author honours student Hayden Ou of UNSW with Dr Nicolas Bedford of UNSW.

First author Mohammed Zubair received a grant from the (AINSE) to support his research at ANSTO.

Layered double hydroxides, materials that have attracted interest for their ability to remove metals, are fairly easy to make and can be modified to improve the way they work.

Because these layers have positive and negative charges, they can be tailored to capture specific substances such as uranium.

Lanthanide dopants, neodymium, europium and terbium, were tested. Adding neodymium to layered double hydroxides (LDHs) improved their ability to selectively capture uranium from seawater, a highly challenging process that scientists have been working on for a long time.

Synthesised materials were characterised using a variety of techniques, including Scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) at ANSTO’s microscopy facility by Dr Daniel Oldfield and at UNSW by Yuwei Yang.

When neodymium was added to LDHs (MgAlNd), these materials chose uranium over ten other more abundant elements found in real seawater.

Importantly, the experiments were undertaken under seawater-like conditions.

A crucial finding was that the dopant, neodymium, changes the way uranium binds to the LDHs.

The research team also used (XAS) and at ANSTO’s Australian Synchrotron to clarify the octahedral coordination environment, oxidation state and adsorption mechanism, respectively. They were assisted by Instrument scientists Dr Jessica Hamilton and Dr Lars Thomsen, co-authors of the paper.

X-ray measurements showed that under seawater conditions, the removal of uranium occurred through a process where uranium atoms formed complexes on the surface of LDHs by replacing nitrate ions in the LDH layers with uranyl carbonate anions from the seawater.

By adding neodymium and other lanthanide elements to the LDH structure, the chemical bonding between metal atoms and oxygen in the LDH became more ionic.

This improved ionic bonding made these materials much better at selectively binding to uranium via ionic surface interactions.

The authors pointed out that the study demonstrated a way to adjust how well a material can capture uranium which could lead to creating new materials that are even better at separating uranium from other substances.

DOI:

The materials were not just useful for taking uranium from seawater but also had the potential to clean up uranium from radioactive wastewater near nuclear power plants.

“There are additional benefits in that these materials are simple and inexpensive to make, making them a cost-effective choice for large-scale uranium extraction,” said Dr Veliscek Carolan.