New research from North Carolina State University provides insights into the earliest stages of Angelman syndrome. The work also demonstrates how human cerebral organoids can be used to shed light on genetic disorders that affect human development.

Angelman syndrome is a genetic disorder associated with delayed development, intellectual disability, speech impairment and problems with movement. A great deal of research has been done on Angelman syndrome, primarily involving laboratory studies of mice and natural history studies of humans. However, while researchers have established that the complex disorder is tied to the behavior of a gene called UBE3A, and strong evidence in mice has shown that prenatal time periods may be important in disease development, researchers had yet to find a way of monitoring the earliest stages of the disease in human neural cells.

“Obviously we cannot do studies on developing humans, so we wanted to know whether it was possible to study the molecular dynamics around UBE3A using cerebral organoids,” says Albert Keung, corresponding author of a paper on the work and an assistant professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering at NC State. “When is the gene turned on? How do drugs affect gene and neuronal functions? Does the gene behave differently in different types of cells? These are complex questions, but we found that you can learn a lot through the cerebral organoid model.”

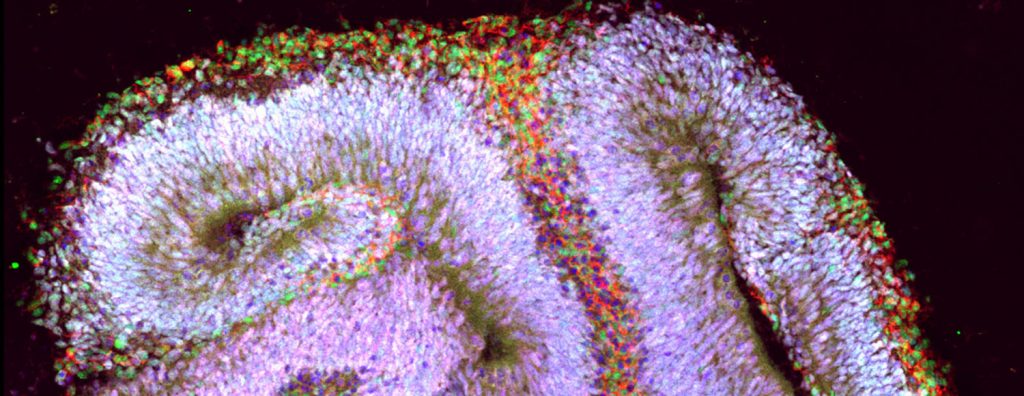

Human cerebral organoids are millimeter-sized tissues comprised of the cell types typically found in the different regions of the brain. They are made by culturing stem cells. For this study, the researchers monitored the behavior of the organoids for 17 weeks after culturing the cells.

For example, the researchers mapped when UBE3A was turned off or on in different types of cells and at different stages of neurodevelopment – as well as where in each cell the gene was active. This can shed light on things such as the extent to which UBE3A might be regulating the activity of other genes, and when the delivery of therapeutic treatments may be most effective.

One of the things the researchers discovered is that UBE3A appears to be playing an important role in the development of brain tissue earlier than anyone knew – potentially even within three weeks of culturing the organoids.

“We had the ability to see how UBE3A’s behavior changed over time in the organoid,” says Dilara Sen, first author of the paper and a Ph.D. student at NC State. “We were also able to see how different drugs affected the gene’s behavior – and how those changes affected the function of neurons in the organoid.”

“This is fundamental, proof-of-concept work,” Keung says. “But hopefully it demonstrates how the cerebral organoid model can facilitate the development of therapeutic strategies for people with Angelman syndrome. We believe the model can do this by advancing our understanding of the disease, which can inform research into possible treatments. We also believe that this model could be used to screen drugs that are candidates for therapeutic interventions. Organoid models aren’t new. But they may be more powerful tools than we previously anticipated.”

The paper, “Human cerebral organoids reveal early spatiotemporal dynamics and pharmacological responses of UBE3A,” is published in the journal Stem Cell Reports. The paper was co-authored by Alexis Voulgaropoulos, an undergraduate at NC State; and by Zuzana Drobna, a research associate professor of biological sciences at NC State.

The work was done with funding from a Simons Foundation SFARI Explorers Grant, under grant number 495112; the ³Ô¹ÏÍøÕ¾ Science Foundation Emerging Frontiers in Research and Innovation program, under grant number 1830910; a ³Ô¹ÏÍøÕ¾ Institutes of Health Avenir Award, under grant number DP1-DA044359; and a fellowship from the American Association of University Women for Sen.