Should American allies be worried that if Donald Trump returns to the White House next year, he will tear apart treaties, recast decades-old international arrangements and adopt a go-it-alone approach to global affairs?

Author

Lester Munson

Non-resident fellow, United States Studies Centre, University of Sydney

Recent comments from Trump NATO allies have put this question on the front burner in Washington and other world capitals.

Trump is, of course, in the middle of a presidential campaign and is seeking to show he would be a very different president from Joe Biden. Given Biden’s difficulties on foreign policy, it is easy to see why.

Biden’s mixed foreign policy record

Biden’s approval numbers are near historic lows – of the job he is doing. In particular, Biden’s foreign policy has been a problem. His plunge in popularity began around the time of the catastrophically US troop withdrawal from Afghanistan two and a half years ago.

Israel’s war against Hamas in Gaza – and the Houthi attacks in the Red Sea and Iranian proxy attacks against American forces in Iraq and Syria that followed – have only made Biden look weaker. In fact, show only of his foreign policy.

A resurgent Iran reminds older Americans of the more than 50 Americans in Tehran in 1979 and then-President Jimmy Carter’s failure to free them – one of the main reasons why Carter the 1980 presidential election to Ronald Reagan. The hostages were freed the day Reagan took office.

Today, Biden faces the same potential election-year problem with the Gaza war. Younger, progressive Americans, as well as Arab-Americans, are more likely to be aghast at Biden’s support for Israel’s assault on Hamas in Gaza and the consequent civilian deaths. Many Biden supporters are concerned this could against Trump in November’s election, particularly in swing states like Michigan, which has a large number of Arab-American voters.

Also working against Biden is the war fatigue felt by many Americans. After 20 years of fighting in Afghanistan and Iraq, many Americans are ready to take a break from global leadership responsibilities.

A long tradition of placing America first

Biden’s foreign policy weaknesses opens the door for Trump to show voters he will take a different approach.

Over the past four decades, starting with Reagan, successful presidential candidates have criticised foreign adventures, instead emphasising domestic investment. Political scientists use the term “” to describe this, but politicians are more likely to use a phrase like “.”

In 1984, for instance, Reagan ran one of the most effective presidential campaign ads in history called “Morning in America”, which depicted a return to domestic tranquillity and prosperity.

In 1992, Democratic strategist James Carville , “It’s the economy, stupid”, which then-candidate Bill Clinton’s campaign evoked successfully to focus on domestic economic issues in his race against President George H.W. Bush.

Then, in 2000, then-Republican challenger George W. Bush the Clinton administration’s focus on ““, comparing it to “international social work”.

When it comes to Trump, bombast is a feature, not a bug. When he ran for the White House for the first time in 2016, he his isolationist, “America first” approach, criticising President Barack Obama and his secretary of state, Hillary Clinton, for their “reckless, rudderless and aimless foreign policy”. He said, if elected,

I will return us to a timeless principle. Always put the interest of the American people and American security above all else.

He has returned to this rhetoric in the current campaign, even encouraging Russia to invade NATO countries that don’t spend the required 2% of their GDP on defence. While offensive at first blush, these comments serve the very useful purpose of showing a huge difference from Biden.

A 19th century, populist world view

It is also important to understand a deeper truth about these comments. In his bones, Trump does not truly value any formal alliances formed before his ascent to power. Call it narcissism or isolationism if you must (and neither is entirely inaccurate), the former president sees formal alliances as a lower priority than fair play and power politics.

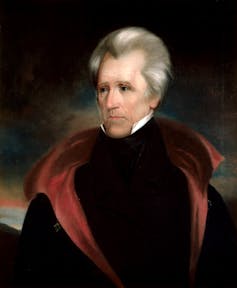

In this, Trump is a prime example of the Jacksonian tradition in American politics. Described best by the scholar and columnist , the Jacksonian tradition is based on the political beliefs of former President Andrew Jackson, who was president from 1829 to 1837.

Jacksonians, like Trump and his most ardent supporters today, have a highly sceptical view of America’s involvement in global affairs. As Mead :

They prefer the rule of custom to the written law, and that is as true in the international sphere as it is in personal relations at home. Jacksonians believe that there is an honour code in international life […] and those who live by the code will be treated under it. But those who violate the code – who commit terrorist acts in peacetime, for example – forfeit its protection and deserve no consideration.

For Jacksonians, when a country welches on its obligations (such as, in Trump’s view, the level of defence spending of many European NATO nations), it is morally right to punish them by calling into question treaty obligations.

Seen as a liar and fabulist by his opponents, Trump embodies this Jacksonian tradition of “customary honour” for his supporters, whose contempt for global elites and international institutions is deep and profound. (Trump was so enamoured with Jackson, in fact, he had a of the former president hanging in the Oval Office.)

This means, if Trump becomes president again, America’s allies, whether in NATO or the Indo-Pacific or elsewhere, will have to de-emphasise lawyerly arguments about international obligations and adapt quickly to the Trump-Jacksonian customary honour approach to diplomacy.

Superficially, this will mean global leaders offering praise for Trump’s various political performances. Going deeper, it also means finding a way to demonstrate that their relationship with the US is congruent with his sense of customary honour (and is also materially beneficial to the US, and maybe even to Trump himself).

The model for this is the late prime minister of Japan, Shinzo Abe. Within days of Trump’s surprising election win over Hillary Clinton in 2016, Abe him at Trump Tower in New York and gave him a gold-plated golf club worth almost US$4,000. Trump immediately identified Abe as “.”

After then-Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull had an with Trump in 2017, the Australian ambassador to the US, Joe Hockey, with Trump.

With good humour and some personal charm, Hockey helped restore the diplomatic relationship – not by emphasising legalistic constraints but by developing a personal relationship that was grounded in common sense and customary honour.

![]()

Lester Munson is a Non-Resident Fellow at the U.S. Studies Centre. Lester Munson has worked for President George W. Bush and congressional Republicans during his public service career in Washington.