New research by The University of Notre Dame Australia has highlighted the lasting impact single use plastics will continue to have on Western Australia’s beaches for years to come, despite ongoing government efforts to reduce their use.

Assisted by a dedicated group of volunteers, the research team collected 5322 individual pieces of litter from Bather’s Beach in Fremantle during a seven-month period from October 2022 to May of this year.

The litter was then sorted and analysed, revealing that 43 per cent was made from single use plastics, with some of those items believed to have been in the water for well over a decade or longer.

One item believed to be a single-serve tomato sauce packet was still in good condition, despite having a use-by date from April 2016. Another item, believed to be the black bottom of an old plastic soft drink bottle, was found on the beach in March this year despite being phased out in the 1990s.

Other items such as plastic bottles were so badly weathered that the research team estimated they had been in the water for well over 10 years.

Drinking straws also regularly washed up on the beach, despite being banned from sale in WA last year. Three drinking straws that can be linked to one particular fast food chain were found on the beach during the study period, even though that company voluntarily phased out their use in 2021.

Lead researcher Dr Linda Davies, from Notre Dame’s School of Arts and Sciences, said the findings demonstrated why current efforts to reduce plastic waste were so important, given the lasting legacy that these plastics have on the marine environment.

“What our research demonstrates is that a large amount of the waste washing around in our oceans has actually been there for an extended period of time,” Dr Davies said. “Even if we were to ban all plastics overnight, our beaches and waterways would continue to be blighted by this problem for years to come.

“Unlike organic wastes, these items never actually break down, even after decades of being smashed about in the ocean. Instead, they simply break apart into ever smaller pieces, eventually turning into harmful micro plastic particles that end up in the food chain and ultimately inside our bodies.”

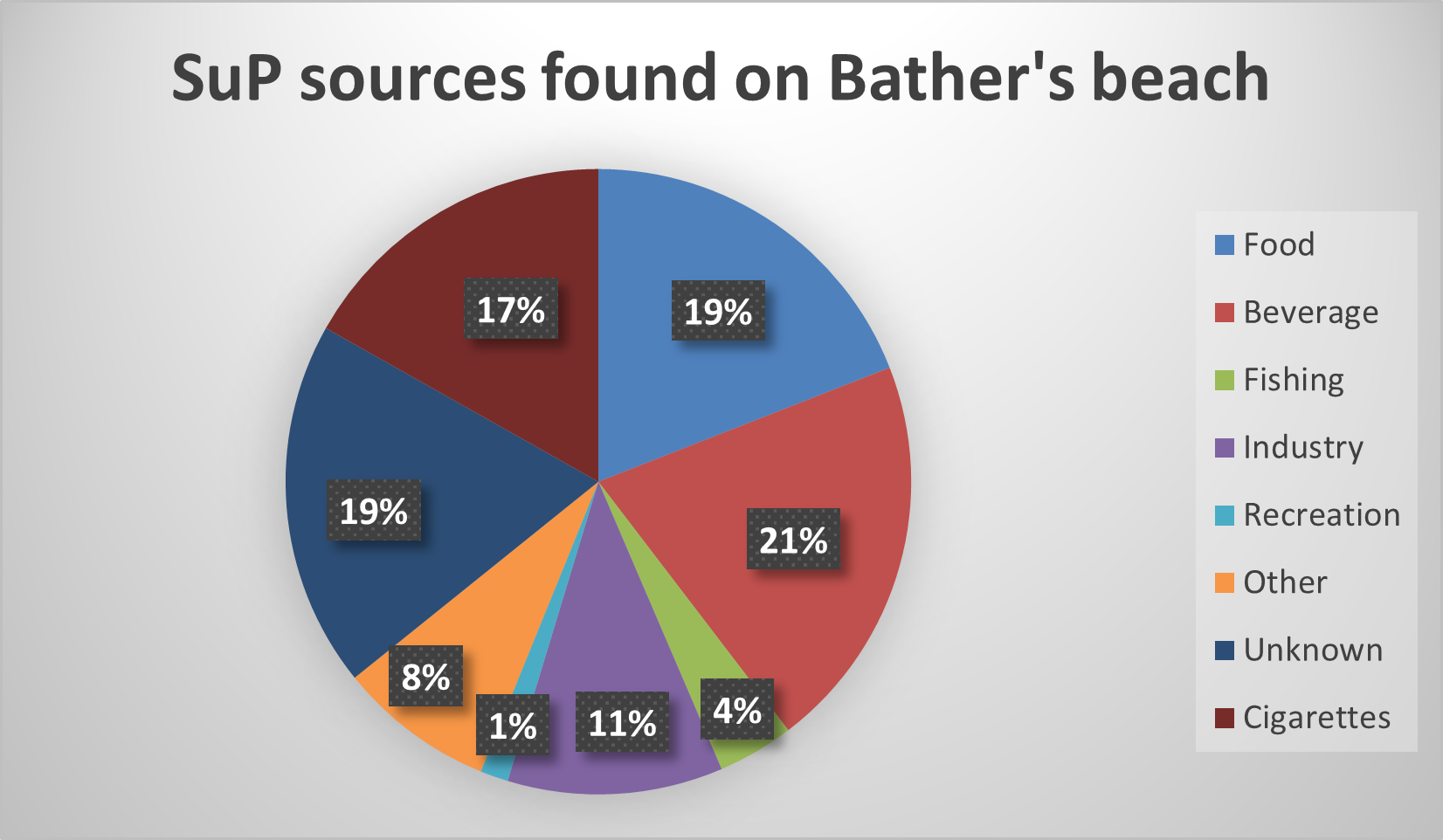

Beverage containers, food packaging and cigarette butts with non-recyclable plastic filters were among the biggest sources of plastic waste, making up 57 per cent of total plastics (see table below for a full breakdown).

As part of the research project, a specially designed seahorse-shaped bin, made by local sculpture artist Melanie Maclou, was erected at Bather’s Bay. The bin was fitted with a combination lock to ensure only those involved in the research project could deposit waste in it.

The waste would then be collected by Dr Davies’ research team, who sorted and analysed it to determine the types of products that are ending up in the ocean, as well as where they were likely to have come from. The data that has been gathered will now be used as a baseline to help monitor the long-term effectiveness of local and state government waste reduction strategies, including WA’s Plan for Plastics.

“By sorting and classifying the waste, we can see that local business, particularly food and beverage outlets, are a major source of the waste that is still going into the ocean down at Bather’s Beach,” Dr Davies said.

“But we can also see that a lot of the waste is coming from further afield, including from ships, storm water outlets, or via the river.

“We plan to share those insights with the local business community to help them understand where their packaging is ending up and the impacts that it is having on our environment.

“Importantly, our data also provides us with a baseline that we can use to monitor the longer-term effectiveness of local and state government waste reduction strategies.”