A new study shows treating insomnia first can lead to 50% better outcomes for people suffering with concurrent insomnia and sleep apnoea.

The ‘double whammy’ of co-occurring insomnia and obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) is a complex problem best managed with non-drug targeted psych interventions, the Flinders UIniversity study has found.

By following simple new guidelines, people with the concurrent conditions reported great improvement to both their sleep, and their health – with about 50% improvement in global insomnia severity and night-time insomnia after six months.

‘Co-Morbid Insomnia and Sleep Apnoea’ (or ‘COMISA’) is a little studied and debilitating disorder which can improve with diagnosis and treatment, including the insomnia as a separate condition. Up to 80% of OSA can be undiagnosed.

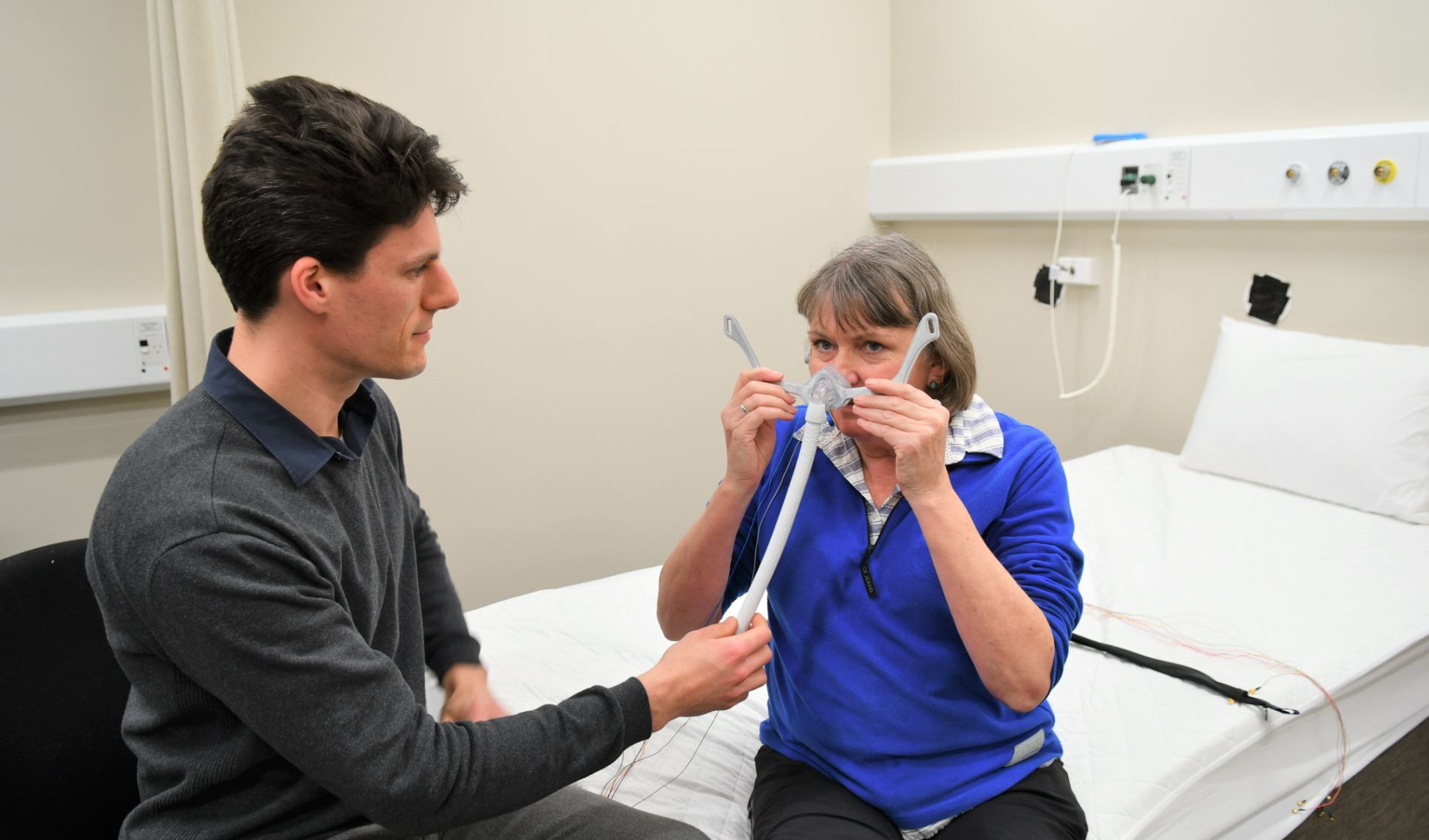

The new NHMRC study of 145 patients aimed to work out better treatments for ‘COMISA’ patients who, in the past, have shown poor results from using continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy, compared to patients who do not report symptoms of insomnia.

As a result, the South Australian and Queensland sleep experts are advising people living with both conditions to be treated first with a targeted, 4-10 week program of cognitive and behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBTi) – before using CPAP machines to reduce the effects of sleep apnoea.

“We found that treating COMISA patients with non-drug CBTi before commencing CPAP significantly improved insomnia symptoms,” says lead researcher Dr Alexander Sweetman, from the Adelaide Institute for Sleep Health at Flinders University.

“Importantly, we also found increased use of CPAP therapy by about one hour per night in patients treated with CBTi and CPAP therapy, compared to a group receiving treatment with CPAP alone.”

OSA patients – who comprise around 10% of the general population – suffer from frequent airway narrowing events during sleep which leads to a poor quality of sleep and reduced daytime functioning.

About one-third of OSA patients also report clinically significant insomnia symptoms, including long-term difficulties falling asleep at the start of the night, or long awakenings during the night.

The study found the new routine resulted in CBTi patients increasing acceptance of CPAP devices by 87% and increased long-term CPAP use by one hour each night over the first four months.

At six months, combined CBTi and CPAP therapy led to significant improvements of:

- 52% in global insomnia severity, compared to 35% in the control group,

- 48% in night-time insomnia complaints, compared to 34%

- 30% in dysfunctional sleep-related cognitions (compared to 10%).

Heart disease, obesity and depression have been connected to insomnia and sleep apnoea, so getting the best therapies are important to health and wellbeing for millions of people around the world, says co-author Professor Doug McEvoy.

“Long-term cardio-metabolic benefits for patients with COMISA is an important consideration, independent of those debilitating symptoms which can be relieved with the right treatment,” Professor McEvoy says.

“This latest study suggests that sleep physicians and clinics should screen for insomnia symptoms and, if present, treat the insomnia with CBTi to improve subsequent acceptance and use of CPAP therapy. This will improve outcomes for both disorders.”

Research at the and CRC for Alertness, Safety and Productivity at Flinders University are studying a range of interventions for sleep disorders, which are costing the Australian economy $26 billion a year in lost productivity and up to $66 billion a year combined with health and wellbeing costs

The new research, ‘ (2019) by A Sweetman, L Lack, P Catcheside, N Antic, S Smith, CL Chai-Coetzer, J Douglas, A O’Grady, N Dunn, J Robinson, D Paul, P Williamson and RD McEvoy has been published in US journal Sleep (Oxford Academic). DOI: 10.1093/sleep/zsz178

Recruitment sites for the study were the Adelaide Institute for Sleep Health. Flinders University, Sleep Health Service, Repatriation General Hospital, Southern Adelaide Local Health Network and Prince Charles Hospital, Brisbane, Queensland.

The research was funded by a │į╣Ž═°šŠ Health and Medical Research Council grant (1049591).