A “game changing” new telescope will soon be blasted into space to embark on a lonely 1.5-million-kilometre orbit around the Sun to provide a clearer view of the ever-expanding universe.

The (JWST) is the largest telescope ever to be launched into space and will be used by University of Queensland researchers to observe asteroids and newborn planets, as well as black holes in distant galaxies.

UQ astrophysicist said he’s excited by the capabilities of the JWST, widely considered as the successor to the famed Hubble Space Telescope (HST), which launched in 1990.

“The JWST will go dramatically beyond what any telescope has been able to do – it will see some of the first stars in the universe, billions of light years away,” Dr Pope said.

“By looking at exoplanets as they transit, it will measure their atmospheric composition and detect water and other molecules that could indicate planets capable of sustaining life.

“It changes the game on how we observe planets, stars, asteroids, and the universe around us.”

After more than a decade of delays, the telescope will be launched in the coming days on a European Ariane 5 rocket from French Guiana, bringing astronomers closer to distant galaxies than ever before.

“One of the main benefits of a space telescope such as the JWST is that it overcomes one of the biggest problems facing astronomers – the atmosphere blocking their view of the wider universe,” Dr Pope said.

“Such a powerful space telescope will put us on the doorstep of some incredible discoveries.”

Dr Pope will be involved in several observation projects, including the kernel phase project, observing distant and hard-to-see stars and planets, and on an aperture masking project to study planets at the moment they form around stars, and on methods to observe asteroids and dwarf planets with greater clarity than ever before.

“One project will use the JWST to study how brown dwarfs form, and since I’ve worked on a similar project for my Honours thesis using data from the HST, my role will be using the very same algorithm to analyse data from the JWST regarding these brown dwarfs,” Dr Pope said.

“Another project will observe the most important asteroids – the only problem is they’re too bright to observe, and images are washed out.

“To deal with this, we’ve developed methods to make it easier to observe these ‘too-bright’ stars, that involves a high dynamic range image processing mode – like you’d use on your phone camera to bring out dark shadows and bright highlights.”

UQ will use the JWST for a series of observation projects aimed at identifying and studying black holes in distant galaxies.

“Specifically, we’ll be searching for supermassive black holes in the centres of nearby galaxies,” Dr Baumgardt said.

“Our aim is to understand the relationship between the mass of both black holes and the galaxies that host them and learn how these supermassive black holes formed.”

Equipped with the far-reaching capabilities of the JWST, Dr Pope said the future of astronomy looks bright, with answers to some of astronomy’s most important questions within reach.

“JWST will give us a clearer picture of the origins of our own Solar System, and our best ever glimpses of the other weird and wonderful systems of planets in the Galaxy.”

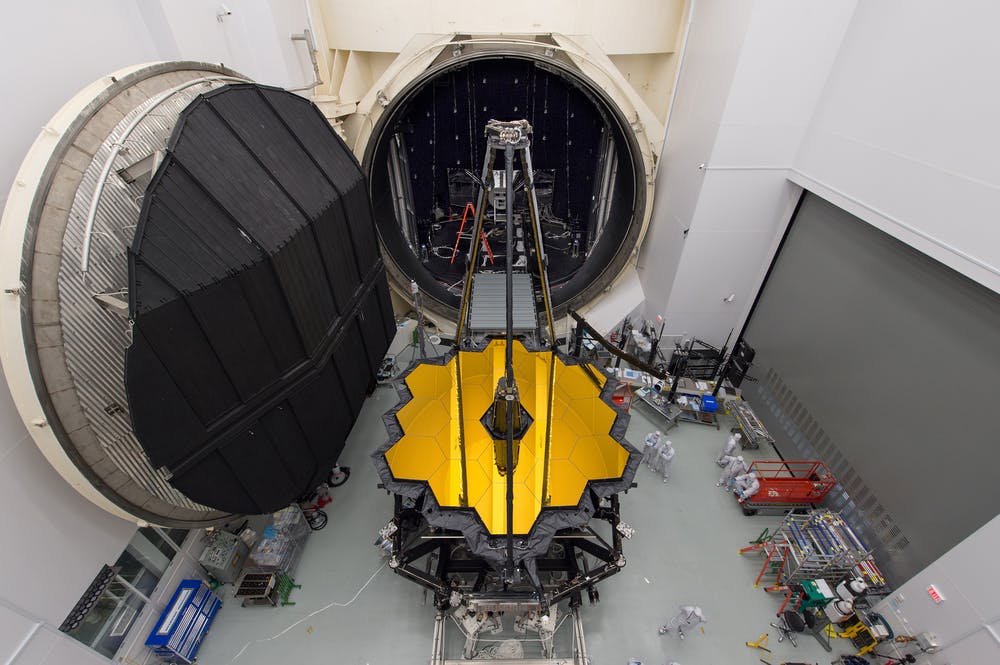

Image above left: Engineers and scientists tested the entire telescope in an extremely cold, low-pressure cryogenic vacuum chamber. NASA/Chris Gunn.