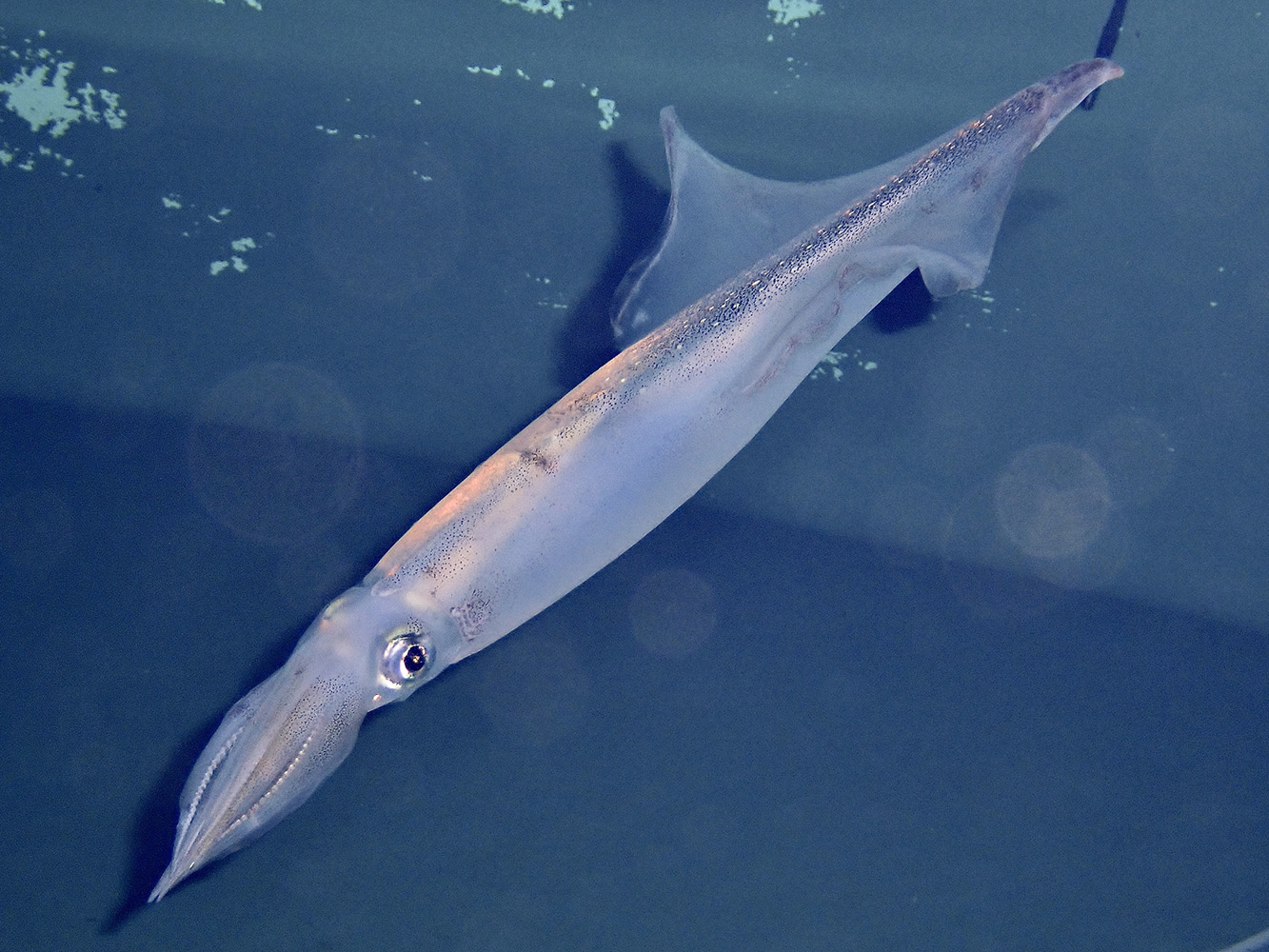

Spear squid. Native to the western Pacific Ocean along the coast of Asia, the spear squid only lives for a year and is a popular food in Japan. © 2024 Shota Hosono

The day a male spear squid hatches determines which mating tactic he will use throughout his life, according to new research. Spear squid (Heterololigo bleekeri) that hatch earlier in the season become “consorts” which fight for mating opportunities. Those which hatch later become “sneakers,” which use more clandestine mating tactics. Researchers found that the mating tactic determined by the birth date was fixed for the squid’s whole life. Understanding how mating tactics are influenced by birth date, and the environmental conditions at that time, can help researchers consider how squid might be affected by climate change and the implications for marine resource management.

What does your date of birth say about you? Maybe you feel it reveals something about your personality, or perhaps even your destiny. For male spear squid, it can tell us a lot about their love life!

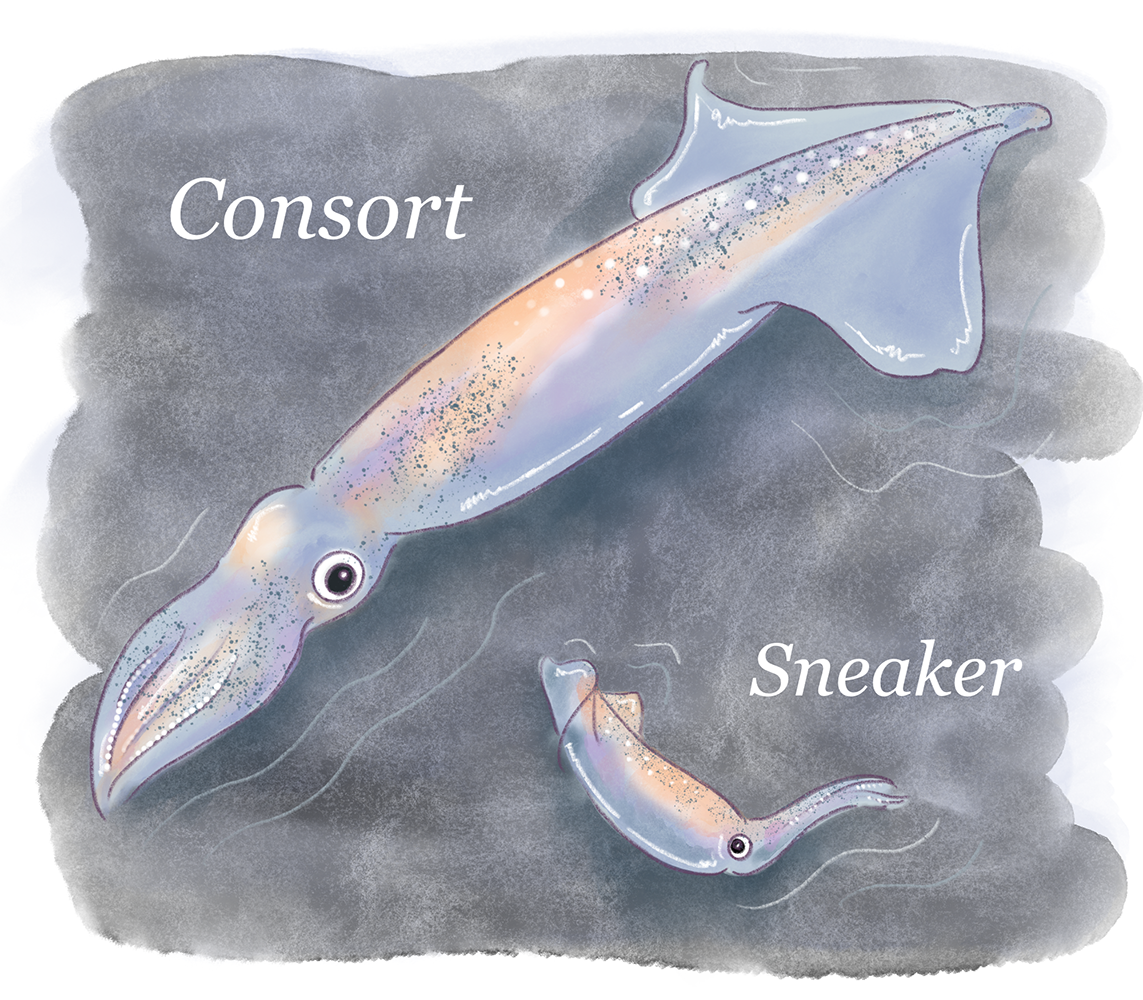

A team of researchers in Japan have found that the mating tactics of spear squid are heavily influenced by the day they were born. These squid can be classified into two types according to their mating techniques: consorts, which fight off rivals to place their sperm inside a female and then guard her while she lays her eggs; and sneakers, which, as the name implies, steal mating opportunities by covertly depositing their sperm on the outside of a female near where she lays her eggs, in the hope of fertilizing them.

Interestingly, this study found that once a squid mating tactic had been determined by their birth date, they stuck with it. Male squid born between early April and mid-July grow large before starting reproduction and become consorts. Squid which hatch later, between early June and mid-August, are smaller when mating season begins and become sneakers. However, even if an early-born squid grew large enough to become a sneaker in the early breeding season, he would postpone maturing and continue growing until he becomes large enough to be a consort. Squid born in early July had a fifty-fifty chance of using either tactic.

Consort and sneaker squid. Consort squid can be considerably larger than sneakers when they mature, growing on average to 300 millimeters (mantle length) compared to 150 mm. However, sneaker squid have been found to have larger and longer-lasting sperm. © 2024 Nicola Burghall

“Our results showed that the hatching date determines the whole life trajectory in this species,” said Associate Professor Yoko Iwata from the Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute at the University of Tokyo. “The difference in hatch date means that the squid experience different environmental conditions in early life, which may influence the growth trajectory. If an extreme environmental event, such as an ocean heat wave, happens during the hatching season, it could affect the squid’s mature body size and subsequent mating tactic. This would also impact the amount that could be commercially caught enormously.”

In total, the team analyzed over 350 squid, which they either caught themselves or took from commercial catch between 2020 and 2023. These are the first reported results which support the “birth date hypothesis” in an aquatic invertebrate. This hypothesis proposes that date of birth influences a male’s reproductive tactics and had previously only been recorded in fish. This new discovery suggests that it may actually occur in a wider variety of animals than previously thought.

One surprising find was that the growth rate of the squid differed to what the team expected. Previous studies have shown that squid are very sensitive to environmental conditions, particularly water temperature. So, the team expected to see this influence squid growth. However, results showed that the growth rate early in life was not so different between consorts and sneakers, even though they grew up during different seasons. This raises new questions about what else may be affecting spear squid growth and reproduction, which the researchers think may be down to a complex mix of environmental factors.

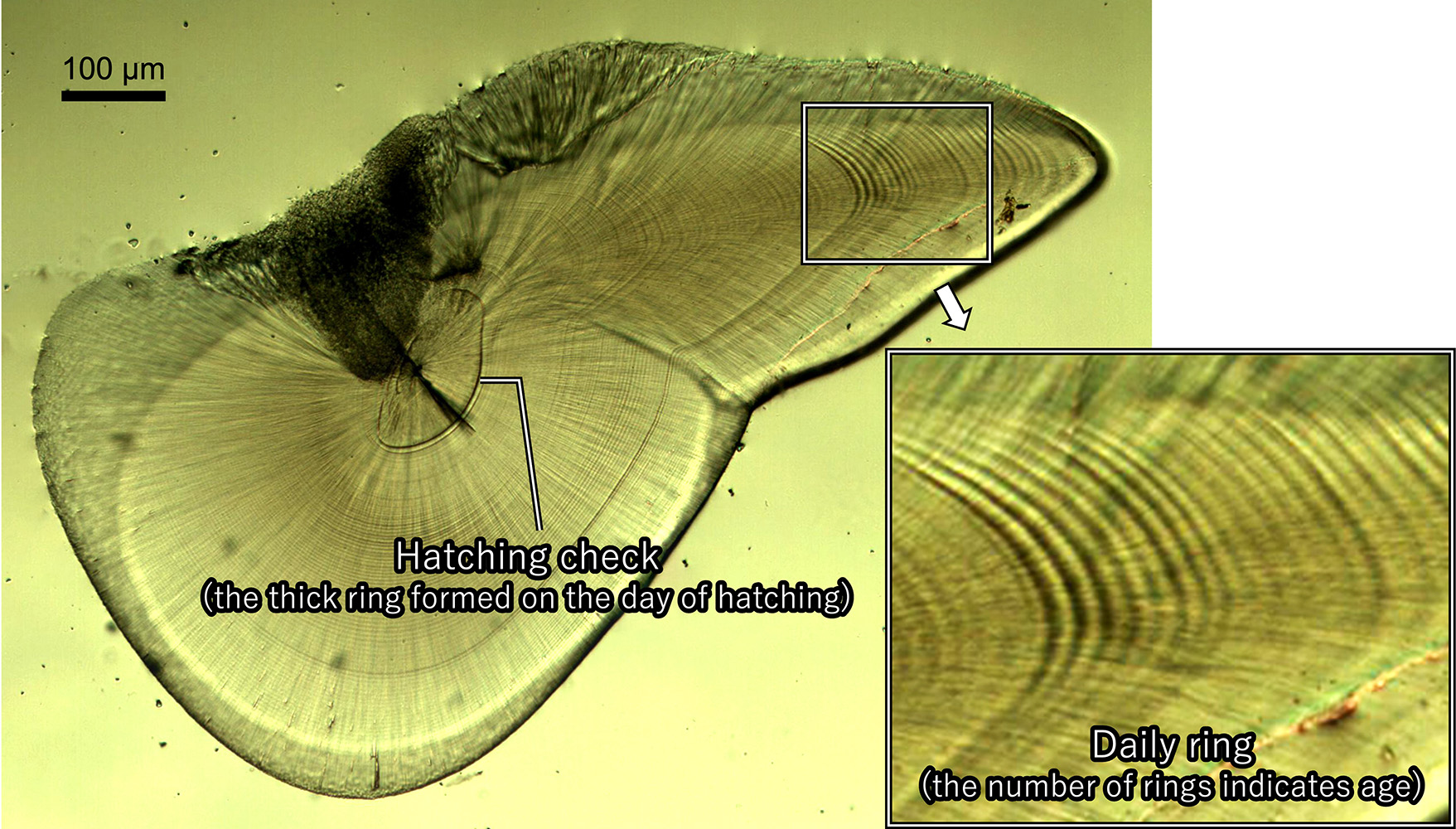

Statolith growth rings. Statoliths are involved in helping the squid keep their balance. They have a thick deposit, called the “hatching check,” marking the day the squid was born. After that, there is one growth increment per day, making it possible to estimate the squid’s age by counting them. © 2024 Shota Hosono

Now the team is analyzing a structure inside the squid called the statolith. Statoliths grow daily and were used in the current study to estimate a squid’s age by counting the number of layers, similar to tree-ring dating. In addition to estimating age, microelements contained within the statolith can be used to estimate the ocean condition experienced by the squid at the time that part of the statolith developed. For example, the element strontium can be used to estimate experienced water temperature. By analyzing these microelements, the researchers want to determine what environments individual squid experienced throughout their early life and create a clearer picture of how this might have influenced their mating tactics.

“I am interested in the evolution of animal survival and reproduction strategies, in other words, its life history; and also phenotypic plasticity, that is, how individuals respond to environmental changes,” said Iwata. “For several reasons I think that spear squid are an ideal organism to study how environmental and ecological conditions can affect life history.”