Developed countries likely to reach USD 100 billion goal in 2023

Climate finance provided and mobilised by developed countries for climate action in developing countries looks likely to reach USD 100 billion in 2023, according to new OECD analysis.

The annual goal for developed countries to provide and mobilise USD 100 billion of climate finance per year for climate action in developing countries was due to have been met in 2020 and to be sustained to 2025.

The last OECD assessment of progress, released in September, showed that , up only 2% from 2018. The USD 100 billion mark is unlikely to have been met in 2020, although the necessary verified data needed to finalise this determination officially will not be available before 2022.

At the preparing for COP26, Canada and Germany agreed, at the request of the incoming UK COP 26 Presidency, to develop a collective Delivery Plan towards meeting the goal as soon as possible. The OECD was asked to provide technical support to this Delivery Plan.

Since that meeting and the release of the OECD 2019 numbers in September, further commitments were made to increase bilateral public climate finance by around USD 10 billion a year on average over the period 2022-2025 relative to the period 2018-19 for those same donors. This is on top of commitments made in 2020 and earlier in 2021 by other countries and increased projections of future climate finance from the multilateral development banks.

Other announcements will be forthcoming over the coming days, with some already provided to the OECD for inclusion into its analysis.

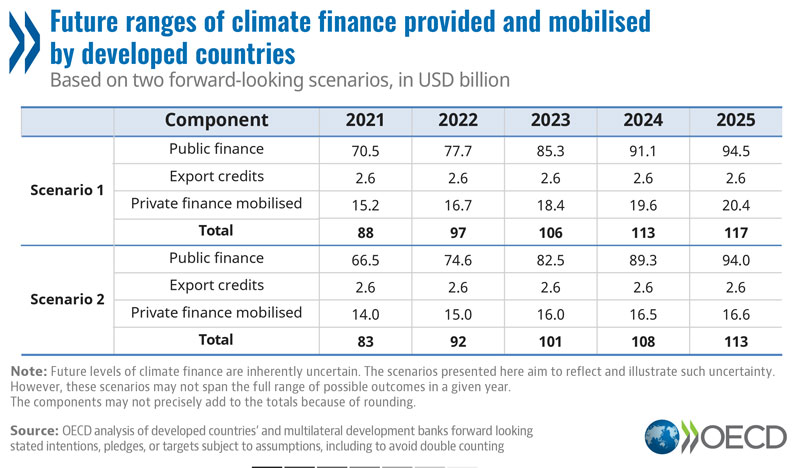

The new OECD analysis released today – – sets out two scenarios for future climate finance.

These are based on detailed OECD analysis of forward-looking public climate finance commitments received from developed countries and projections of climate finance from Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs), communicated in the context of the donors’ .

“It is critical that we reach the USD 100 billion goal of climate finance provided and mobilised by developed for developing countries as quickly as possible. Based on the information we have received, our analysis shows that developed countries intend to significantly increase climate finance provided and mobilised in coming years, which is of course welcome. Our OECD analysis of donor information indicates that 2023 is the year when the goal is likely to be met. This level of finance must then be sustained throughout 2024 and 2025.” OECD Secretary-General Mathias Cormann said. He added that, “While a number of factors, such as the capacity to get relevant projects underway within the intended time frames, will influence exactly when the USD 100 billion goal is achieved, it is vital for developing countries to have a good understanding of developed countries’ intentions in advance of COP26 in Glasgow starting next week.”

Following an analysis in 2016 of estimated climate finance in 2020, thisis the second forward-looking output by the OECD in relation to the USD 100 billion goal. Such analyses complement regular OECD assessments of progress towards the goal, using the same methodology and definitions but carried out retrospectively when the necessary verified data becomes available.

The information on future levels of public climate finance provided to the OECD as part of this exercise varies greatly in level of precision, detail and implied assumptions.

The pace at which climate finance can be scaled up in practice will depend on many factors including macroeconomic conditions, globally and in developing countries, as well as capacity building and the development of climate project pipelines.

Attempts to quantify future levels of aggregate climate finance are, therefore, inherently uncertain.

The two scenarios used by the OECD provide two distinct developments for future levels of climate finance in order to illustrate the range of uncertainty. They should not be interpreted as forecasts and may not cover the full range of potential outcomes.

The first scenario assumes that public finance is scaled up in line with the information provided, subject to OECD checks to standardise the information and avoid double counting. It also assumes that private finance mobilised by this public finance increases in line with the lowest value of the private to public ratio observed in the 2016-19 period. Given shifts in the expected composition of public finance portfolios, this implies increased rates of private finance mobilisation for relevant projects over the period and results in rising volumes of private finance over the period.

The second scenario factors in issues that may result in lower-than-targeted levels of climate finance. These include the potential impact of near-term macroeconomic risks in developing countries, capacity constraints exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, and intended shifts in the composition of providers’ portfolios in relation to increasing the share of adaptation finance, of grant financing, and of financing for Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and Small Island Developing States (SIDS). The nature of this exercise did not allow for a quantitative aggregate estimate of these portfolio changes over time. However, many providers have made clear their intention to scale up finance for adaptation in both relative and absolute terms within their climate finance portfolios. This shift in portfolio composition is built into the calculations, but the precise numbers used represent the OECD’s best estimate informed by historic trends rather than any quantified information from donors.

In this context, Mr Cormann emphasised that, “It is of utmost importance that climate finance is aligned with the priorities of partner countries – for example, as highlighted in their ³Ô¹ÏÍøÕ¾ly Determined Contributions or reports to the UNFCCC. This will allow climate finance to respond to stated needs, particularly to support poor and vulnerable countries building resilience against the growing impacts of climate change. I welcome the increased emphasis on this in the developed countries’ Delivery Plan.”