An invention made from waste polystyrene that generates static electricity from motion and wind could lower power usage by recycling waste energy in air conditioners and other applications.

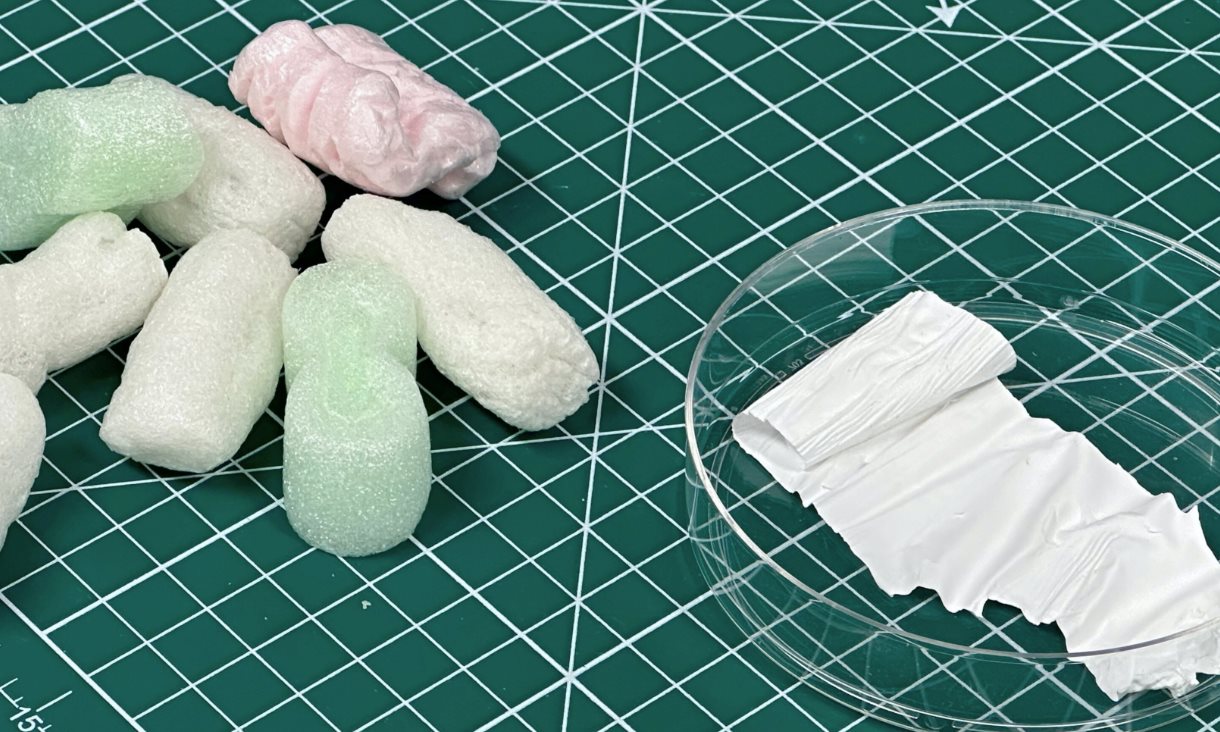

More than 25 million tonnes of single-use, polystyrene packaging materials are made globally each year, but only a tiny fraction is recycled – most of it goes to landfill once it has served its purpose.

The innovation by RMIT University in collaboration with Riga Technical University in Latvia helps address this waste challenge by finding a practical use for the material.

RMIT has filed a provisional patent application for this invention and is now seeking industry partners to invest in developing it for commercial technologies.

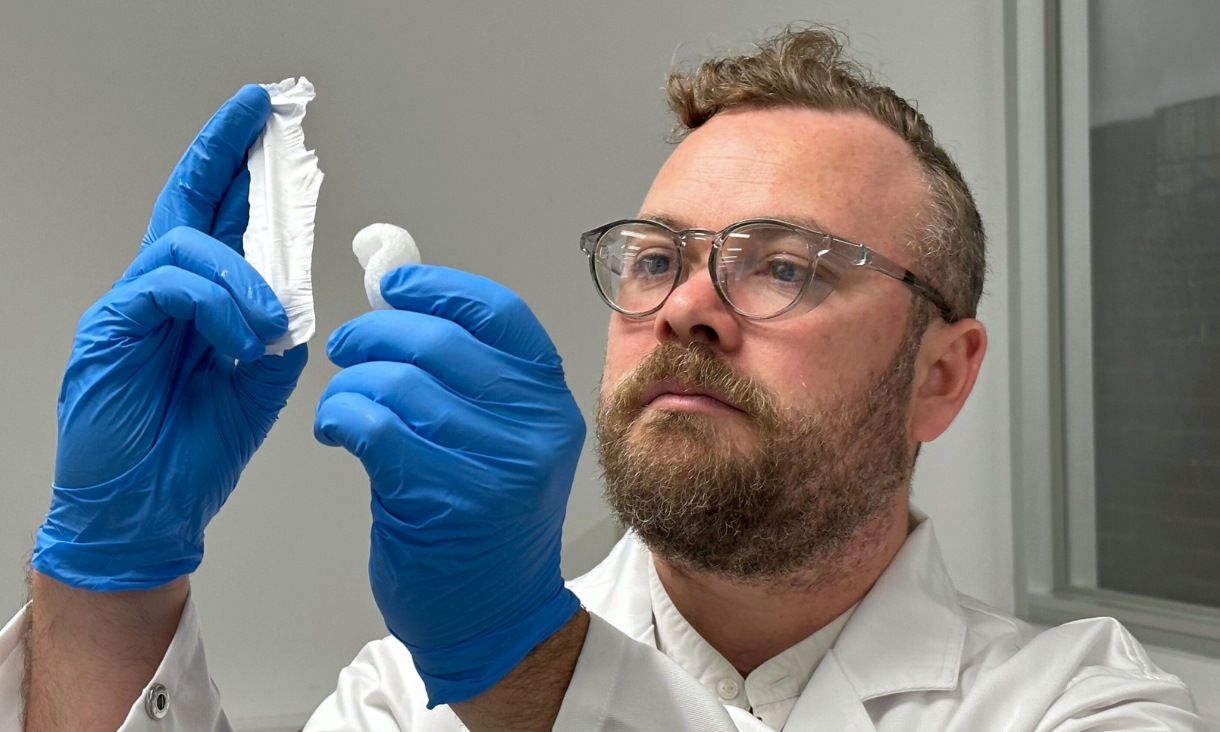

Dr Peter Sherrell with the invention (left) and polystyrene packing material that it is made from. Credit: Seamus Daniel, RMIT

Lead researcher Dr Peter Sherrell, from RMIT, said the innovative thin patch, made from multiple layers of polystyrene each around one-tenth the thickness of a human hair, produced static electricity.

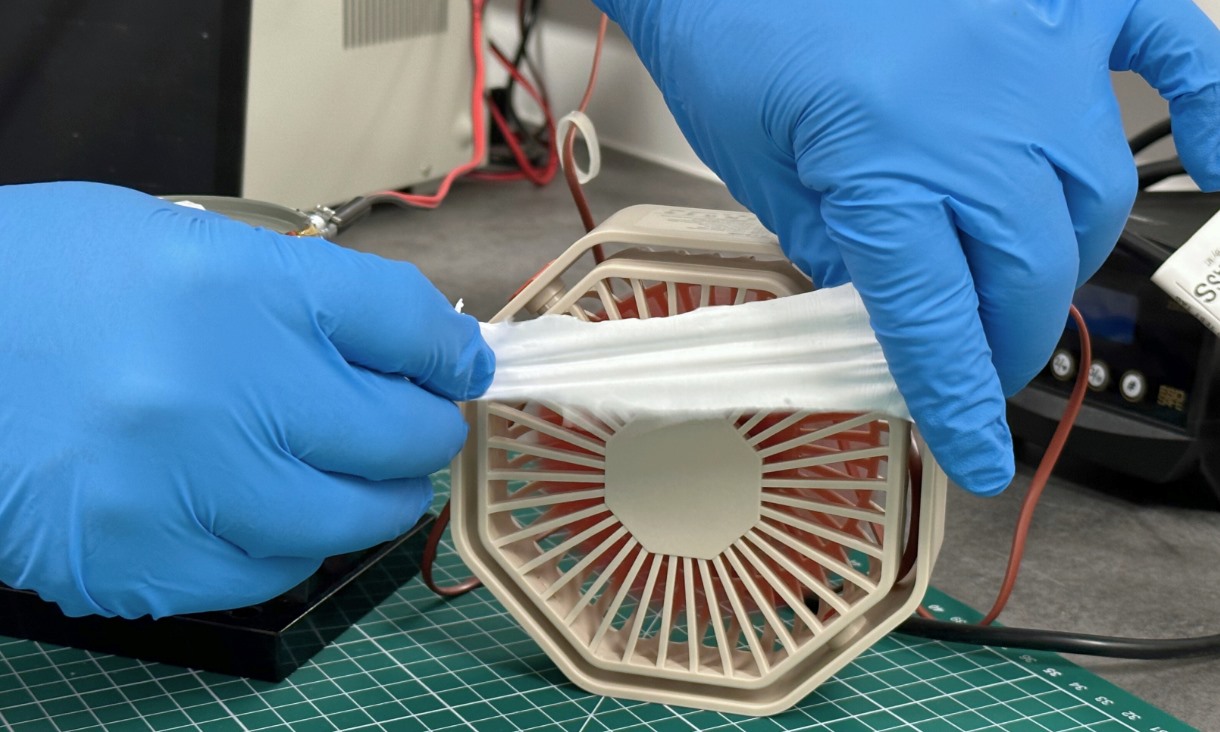

“We can produce this static electricity just from air blowing on the surface of our clever patches, then harvest that energy,” said Sherrell from the .

“There’s potential for energy from the turbulent exhaust of air conditioning units to be collected that could reduce the energy demand by up to 5% and, ultimately, lower the carbon footprint of the system.”

The maximum voltage that the devices were able to produce in experiments was around 230 volts, which is a comparable voltage to mains voltage in homes, though at much lower power.

“The biggest numbers come from a compression and separation, where you’ve got faster speeds and bigger motion, while smaller motion generates less energy,” Sherrell said.

“This means that in addition to air conditioners, integrating our patches in high traffic areas such as underground walkways could supplement local energy supply without creating additional demand on the grid.”

More energy could be harvested with additional layers of polystyrene, Sherrell said.

“The great thing here is the same reason that it takes 500 years for polystyrene to break down in landfill makes these devices really stable – and able to keep making electricity for a long time.”

The research underpinning the static electricity invention is published in .

An invention made from waste polystyrene that generates static electricity from motion and wind could lower power usage by recycling waste energy in air conditioners and other applications. Credit: Seamus Daniel, RMIT

Solving the mystery of static electricity for practical applications

The phenomenon of static electricity has been observed for thousands of years and is well understood at the macroscopic scale, but it has been a mystery at the nanoscale – until now.

“We’ve figured out how to make the insides of reformed polystyrene rub across each other in a controlled way, making all the charge pull in the same direction to produce electricity,” Sherrell said.

“Over the past few years, we’ve been gaining a better understanding about what is happening.

“Plastics are like millions of little strands and when you put two plastic films together these strands get knotted together.

“When these knots break, there’s a little bit of charge on each part of that broken bond.”

Researchers have turned polystyrene packaging materials into an innovative thin patch, made from multiple layers of polystyrene each around one-tenth the thickness of a human hair, which produces static electricity. Credit: Seamus Daniel, RMIT

Next steps

The team has explored the use of other single-use plastics to create energy-generating patches.

“We’ve studied which plastic generates more energy and how when you structure it differently – make it rough, make it smooth, make it really thin, make it really fat – how that changes all this charging phenomenon,” Sherrell said.

“The culmination of all our learning has gone into developing these simple little patches that can create quite a large amount of energy.

“The impact of this research now relies on the development of devices for a range of commercial applications with industry partners.”

‘‘ is published in Advanced Energy and Sustainability Research.