Summary:

- New research reveals the suffering of people whose dogs died after eating 1080 poison baits.

- This is the first qualitive study to give voice to people whose dogs have been harmed by 1080.

- The research team, including Dr Adam Cardilini, Dr Alexa Hayley and Associate Professor Bill Borrie, hope the results will inform decision-making by the government agencies, farmers and conservation organisations that use the poison.

Australia’s use of 1080

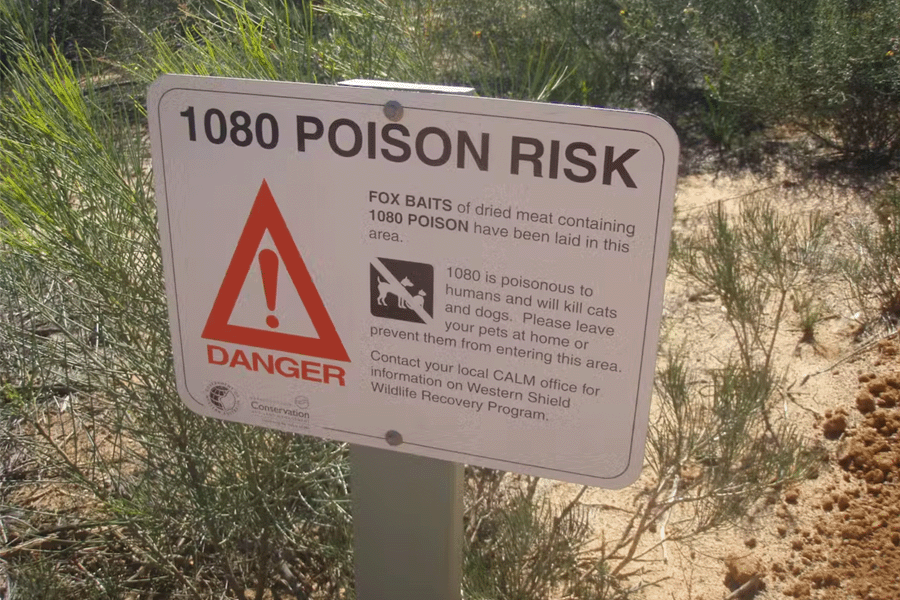

Sodium fluoroacetate poison baits, otherwise known as 1080, are routinely used to kill unwanted ‘pest’ animals in Australia. This includes foxes, rabbits, cats, pigs and wild dogs, including dingoes.

The poison is derived from a naturally occurring compound (potassium fluoroacetate) found in many Australian plants. This means Native Australian animals have developed a varying degree of tolerance to 1080.

But companion animals, including dogs, are also vulnerable to ingesting the baits.

A Deakin University team – comprised of Dr Adam Cardilini, Dr Alexa Hayley and Associate Professor Bill Borrie – interviewed seven people about their dogs’ deaths from 1080 poisoning to understand its impact on dog guardians and their relationships with other animals.

The consequences: ‘No control over what his body was doing’

The study revealed how a brief encounter with 1080 had traumatic and life-altering consequences.

The participants shared uniquely personal stories, yet strikingly all identified the experience of watching their dog die from 1080 poisoning as ‘horrendous’ and ‘horrifying’.

Many dog guardians interviewed described feeling powerless watching their companion suffer.

As one participant told the research team:

‘He was just running away from pain […] He was running that fast and he obviously had no control over what his body was doing, he just hit the fence at full speed, it dropped him to the ground and he’s on the ground snarling and biting and whatnot, at himself, at me, anyone who tried to get near.’

Many participants shared feelings of guilt and anger toward themselves after the 1080 baiting experience:

‘Honestly it nearly destroyed me. I was utterly devastated and I just, I couldn’t let go of that guilt from letting her down, letting the dog down. So I just, I watched all these dog 1080 videos on YouTube on how they were dying cause I thought, I should watch it, I should see what I put that dog through. That was just awful watching all those videos but I just thought, no, I deserve it.’

What happens if my dog ingests 1080?

Dr Cardilini, Dr Hayley and A/Prof. Borrie explain the time-lag between ingestion and signs of toxicity can be anywhere between 30 minutes and 20 hours.

Symptoms of 1080 poisoning include:

- frenzied running

- uncontrollable vomiting, urinating and defecation

- howling and ‘screaming’

- failure to respond to guardian

- confusion and fear

- coma and finally,

- death

There is no specific antidote for 1080 poisoning, however veterinary treatments can assist in your dog’s survival. If 1080 is ingested dog guardians should:

- Seek immediate vet care

- Contact the animal poisons hotline in your state

- Take a photo of area or anything eaten

- Keep your dog quiet and securely restrained during transport to prevent it hurting itself or others and slow energy use

- If vomiting occurs, it will be toxic and can poison other dogs or pets if not cleaned up

Call for 1080 ban

All the study’s participants said they did not believe any animal should be exposed to 1080 baiting, regardless of species or status. They were angry that such a violent management approach was employed that led to their dog’s suffering and death. One interviewee said:

‘What an inhumane thing to do to any living creature. […] I am just angry that this is happening in Australia, I really am. We are such a progressive country. It’s banned in so many parts of the world. And Australia, of all places, is still using it. […] it’s just not Australian to see a wild animal, never mind a dog that you love, die like that.’

Some interviewees felt they also had a responsibility to inform others of the risks of 1080 baiting:

‘It’s just consumed us. We want people to be aware. There is not enough awareness about it. Most people that we have spoken to have said that they have never heard of 1080. The people that have heard of it, most of them weren’t aware of the effects of it.’

Australia remains only one of a handful of countries that allow the use of 1080 baits.

There have been to ban 1080. The research team believes a more compassionate approach is needed: one that values the interests and agency of both wild and companion animals.

They hope the results will inform decision-making by government agencies, farmers and conservation organisations that use the poison.

Dr Adam Cardilini

Dr Adam Cardilini is an environmental scientist and he investigates how our relationship with non-human animals shapes science, the environment and society.

Dr Alexa Hayley

Dr Alexa Hayley is a behavioural scientist within Deakin University’s School of Psychology. Her work focuses on human-animal relationships, stigmatised identities, and wellbeing.

Associate Professor Bill Borrie

Associate Professor Bill Borrie is a conservation social scientist and his research focuses on human-nature relationships, pro-environmental behaviour, and quality visitor experiences. He is a Fellow of the Academy of Leisure Sciences and has received an Excellence in Wilderness Stewardship Research Award from the Chief, U.S. Forest Service.