A deep dive into stock assessments of fisheries around the world has revealed their sustainability is overstated – and it has implications for fisheries management and consumer awareness.

Stock assessments are conducted regularly to measure the impact of fishing on fish and shellfish populations in global fisheries management regions. These assessments inform approaches for preventing overfishing, rebuilding overfished stocks and protecting marine ecosystems.

In a new study , a research team led by the University of Tasmania’s Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies (IMAS) compared past and recent stock assessments across 230 fisheries worldwide.

“Independent scientific monitoring is essential for accurately assessing fish stock sustainability,” said IMAS marine ecologist and lead author, Professor Graham Edgar.

“This study was an opportunity to compare the stock status estimated in a given year, such as 2010, with a more recent revised estimate for that same year – and we found that the earlier stock assessments were often too optimistic about the number of fish in the ocean.”

The study showed an inconsistency in stock assessments, with a strong pattern of over-estimating a fishery’s population status for stocks that were most depleted. Fish stock biomass was overestimated by an average of 11.5%.

“Depleted fish stocks are often the most contentious,” Professor Edgar said.

“When an assessment finds a stock is overfished, fisheries management needs to make tough decisions about reducing fish catches to reverse the trend in stock declines. This includes reducing catch limits, which will ensure the fish stock can continue to support food and jobs into the future.”

IMAS fishery scientist and study co-author, Associate Professor Chris Brown, said the rising trends in the biomass of overfished stocks noted in some stock assessments often disappeared in later assessments, suggesting they were too optimistic about the pace of recovery in overfished stocks.

“When management put limits on catches, many overfished populations have failed to recover as quickly as expected, so our study suggests the assessment tools being used are too optimistic about the real recovery potential,” he said.

The study also found that fish stocks with low economic value were more susceptible to inaccurate assessments.

“Stocks with low economic value will usually have less scientific data to inform the assessments – and this may impact the ability to accurately assess stock status,” Associate Professor Chris Brown said.

IMAS researcher and co-author, Dr Nils Krueck, said many fishery scientists around the world acknowledge the issues highlighted in the study.

“I study and assess fish populations myself, so I believe it’s vital to bring these issues to the public’s attention. This will hopefully lead to improvements in the way we interpret and act on uncertain assessment outcomes to achieve fisheries sustainability globally,” he said.

“It looks like we’re on the right track though, with many assessment scientists reporting that retrospective analysis of model predictions is becoming part of the workflow.”

The study highlights ways to improve the accuracy of fish stock assessments, such as expanding independent fisheries monitoring and changing stock assessment protocols.

“This could include establishing a ‘red team’ that looks at potential worst case scenarios and works to prevent the collapse of fish biomass,” Professor Edgar said.

“Our study clearly shows we need to take a much greater precautionary approach to protect vital fish stocks around the world – for sustainable fisheries and healthy oceans, and ultimately for our own food security.”

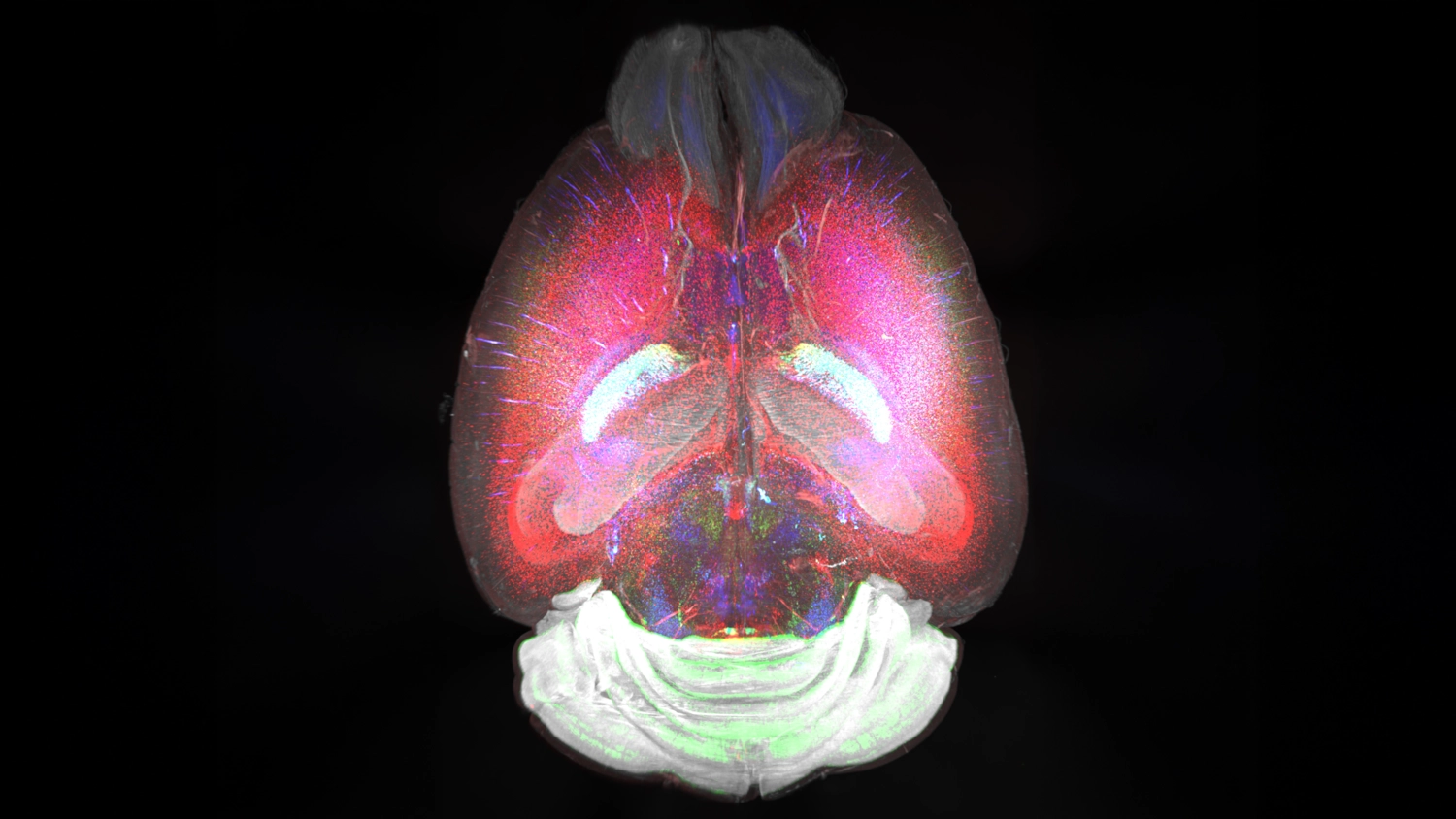

Cover image credit: Jason Washington | Ocean Image Bank