A quiet revolution in Sydney’s eastern suburbs seeks the most vulnerable hospital patients and provides them with access to justice.

George (not his real name) had repeatedly asked his landlord to repair the broken window seals in his home. The mould and draughts they caused were dangerous for his compromised immune system. The 60-year-old was undergoing chemotherapy as an outpatient and couldn’t move out of his social housing. His doctors noted significant psychological distress from the landlord’s inaction.

It was only after an intervention from the Kingsford Legal Centre (KLC) that the landlord promptly made the repairs.

When the landlord hesitated to pay George compensation for causing psychological harm, the matter went to a full hearing. KLC argued the case at no cost to George, using his medical records as evidence. They won. George was compensated and could focus on recovery.

George is one of almost 450 people aided by the KLC Health Justice Partnership (HJP) – run with the Prince of Wales Hospital and the Eastern Suburbs Mental Health Service – since its inception five years ago. A recent independent evaluation of the service has revealed that the Partnership assists people least capable of seeking legal advice during a medical crisis and alleviates pressure on Australia’s public health system.

The evaluation, 5 Years of Impact, highlights the Partnership’s key achievements, which include resolving 132 complex cases for patients experiencing complicated health problems (such as psychological distress and mental illness) and saving healthcare workers up to three hours per patient referral.

KLC Director Emma Golledge says the evaluation demonstrates the benefits to individuals, health professionals and the health system in providing lawyers to patients.

“While the HJP is a simple idea, the evaluation data shows life-changing results that will have positive impacts on the community in the longer term. We hope that this groundbreaking Partnership can continue as we are currently only funded until the end of this financial year,” says Ms Golledge.

Reaching the most vulnerable people in our communities

KLC Deputy Director Dianne Anagnos says that psychological distress and mental illness are often contributing factors to legal problems.

“We see people at a time of crisis in their lives,” says Ms Anagnos. “They should be focusing on their health, but they have incredibly stressful legal issues to deal with on top of everything else. The HJP meets them where they are, in an early intervention model that addresses legal problems before they cause more harm to vulnerable people.

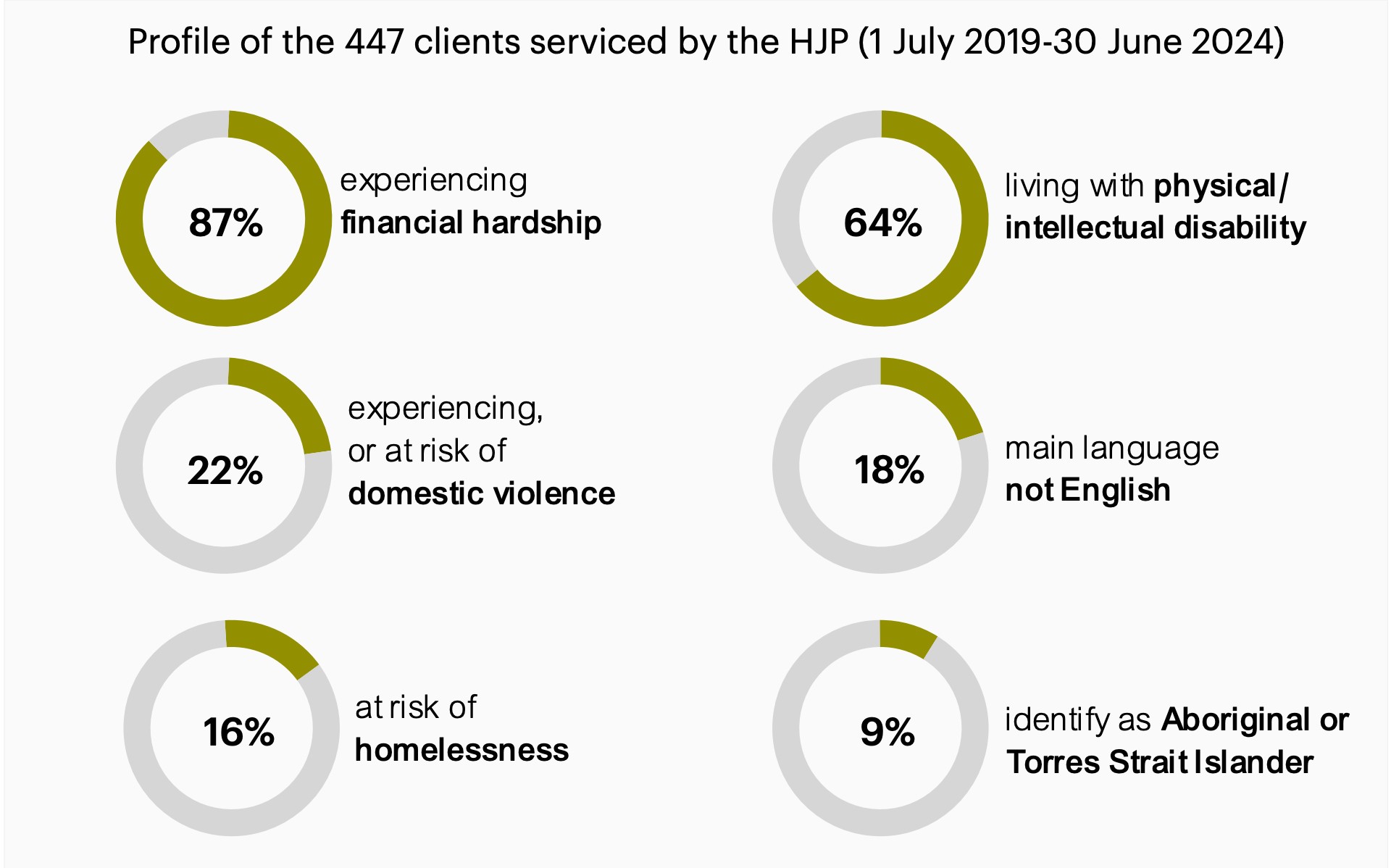

“The 5 Years of Impact evaluation compared the people who come to us through the HJP against the people who come to our community legal centre and found the patients are more likely to be living with a disability, experiencing financial hardship, facing domestic violence, and/or being homeless or at risk of homelessness.”

Ms Anagnos says the evaluation found that KLC also reaches slightly more Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people through the hospital than at the Centre, but fewer people who speak English as a second language. She says understanding why this gap exists presents an opportunity to reach more vulnerable people in future.

Client profile infographic from 5 Years of Impact: Evaluation of the HJP Between KLC, POWH and the ESMHS | NSF Consulting

Personally distressing and complicated legal situations

“The legal assistance we offer is particularly aimed at people with complex needs,” says Ms Anagnos. “Most of the people we see have multiple issues across different areas of law.

“For example, we had a client who needed a long stay in hospital, but he’d run out of sick leave and was falling behind on credit card payments. We were able to advise him of his legal entitlements regarding employment, social security and financial hardship. We also provided him with a letter he could submit to his bank to freeze repayments.”

Ms Anagnos says the KLC solicitor visits the hospital once a week to collaborate with health workers and provide detailed legal assistance to patients, such as advising them of their rights and entitlements, or helping them complete forms and write letters.

“They also assist in various ongoing ways, such as representing patients in courts and tribunals, advocating on their behalf with banks, government departments, and police, and preparing end-of-life documents. If the patient is discharged from the hospital before their matter is resolved, we continue assisting them.”

The types of legal issues reported in 5 Years of Impact span tenancy and housing, credit and debt, social security, consumer claims, criminal charges and apprehended violence orders, victim’s compensation (particularly regarding family violence), enduring guardianship and powers of attorney, and formal complaints about government services and departments.

Beyond assisting individual clients, the KLC Health Justice Partnership also advocates for law reform and provides legal education and training to the broader community.

Professor Andrew Lynch, Dean of UNSW Law & Justice, says the Partnership gives UNSW students invaluable opportunities and first-hand experience of lawyers collaborating with other professionals.

“The HJP deepens our students’ understanding of the disadvantage which persists in our community and the responsibilities they will carry as members of the profession to address this, including through alleviating the stress and health-harming consequences of legal problems,” says Prof. Lynch.

Health justice partnerships began forming in Australia 10 years ago when practitioners noticed patients discussing legal problems with their doctors instead of lawyers. Today, 129 formal partnerships operate across Australia, each adapting to their local community’s changing needs. Industry insiders call the partnerships a ‘quiet revolution’.

Key Facts:

A partnership between mental healthcare workers and community lawyers is helping prevent vulnerable people from falling into deeper disadvantage.