Undersea laboratory. The gold plaque commemorates the installation. It is probably the only public road tunnel in the world that is also a working science laboratory. ©2022 Tanaka et al.

Highly energetic particles called muons are ever present in the atmosphere and pass through even massive objects with ease. Sensitive detectors installed along the Tokyo Bay tunnel measure muons passing through the sea above them. This allows for changes in the volume of water above the tunnel to be calculated. For the first time, this method was used to accurately detect a mild tsunami following a typhoon in 2021.

In the time it takes you to read this sentence, approximately 100,000 muon particles will have passed through your body. But don’t worry, muons pass through ordinary matter harmlessly, and they can be extremely useful too. Professor Hiroyuki Tanaka from Muographix at the University of Tokyo has made his career out of exploring applications for muons. He’s used them to see inside volcanoes and even detect evidence of ancient earthquakes. Recently, Tanaka and his international team of researchers have turned their focus to meteorological phenomena, in particular, tsunamis.

In September 2021, a typhoon approached Japan from the south. As it neared the land it brought with it ocean swells, tsunamis. On this occasion these were quite mild, but throughout history, tsunamis have caused great damage to many coastal areas around Japan. As the huge swell moved into Tokyo Bay, something happened on a microscopic level that’s almost imperceptible. Atmospheric muon particles, generated by cosmic rays from deep space, were ever so slightly more scattered by the extra volume of water than they would be otherwise. This means the quantity of muons passing through Tokyo Bay varied as the ocean swelled.

“The Tokyo-bay Seafloor Hyper KiloMetric Submarine Deep Detector (TS-HKMSDD) is the first underwater muon observatory in the world, and it detected varying muon activity during the tsunami,” said Tanaka. “This variation corresponds to the ocean swells which were measured by other methods. Combining these readings means we can use muographic data to accurately model changes in sea level, bypassing other methods which come with drawbacks.”

There are other ways to measure changes in sea level, with physical mechanisms such as tide gauges, satellites, buoys, or sensors on the sea floor itself. But the TS-HKMSDD and future instruments based on it, installed in undersea tunnels, can be cheaper to build and run, easier to access, and they don’t suffer from physical wear and tear as they have no moving parts. Critically though, the data from TS-HKMSDD is both real time and highly accurate, two key criteria that could make it suitable for a reliable early warning system.

“Thanks to the success we’ve had from early tests such as this, similar systems are already being trialed in the U.K. and Finland,” said Tanaka. “Obviously, an undertaking like this comes with challenges and installing delicate instruments in a busy tunnel could be difficult. But we are grateful for the cooperation of the agencies responsible for the Tokyo Bay tunnel. To the best of my knowledge, the tunnel is now the first active national road in the world defined as a laboratory.”

Tanaka and his team have many other ways in store to make use of muons, including a possible way to accurately synchronize time around the world, and, related to that, a spatial positioning system far more accurate than current GPS.

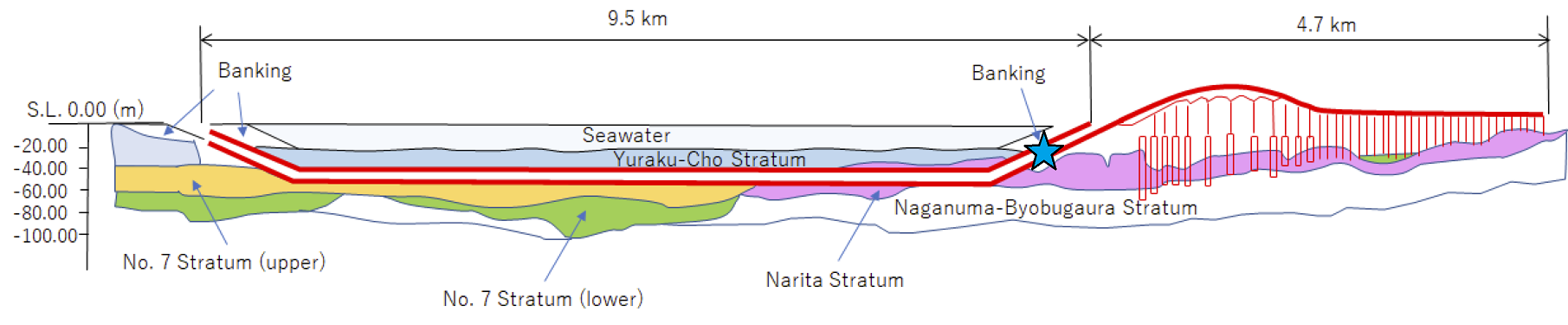

Tokyo Bay tunnel. A cross-section diagram details how the tunnel is situated below Tokyo Bay and the blue star marks the location of the muographic instruments. ©2022 Tanaka et al.