Researchers from the University of Toronto and the California Institute of Technology have designed a new system for efficiently converting CO2, water and renewable energy into ethylene – the precursor to a wide range of plastic products, from medical devices to synthetic fabrics – under neutral conditions. The device has the potential to offer a carbon-neutral pathway to a commonly used chemical while enhancing storage of waste carbon and excess renewable energy.

“CO2 has low economic value, which reduces the incentive to capture it before it enters the atmosphere,” says and project lead Ted Sargent of the Faculty of Applied Science & Engineering. “Converting it into ethylene, one of the most widely-used industrial chemicals in the world, transforms the economics.

“Renewable ethylene provides a route to displacing the fossil fuels that are currently the primary feedstock for this chemical.”

Last year, Sargent and his team published a paper in Science describing how they used an electrolyzer – a device that uses electricity to drive a chemical reaction – to convert CO2 into ethylene with record efficiency. In this system, the three reactants – CO2 gas, water and electricity – all come together on the surface of a copper-based catalyst.

Though the device was a breakthrough for the team, there was still room for improvement. The latest version, described in a paper , further modifies the catalyst in order to enhance the system’s performance and lower its operating cost.

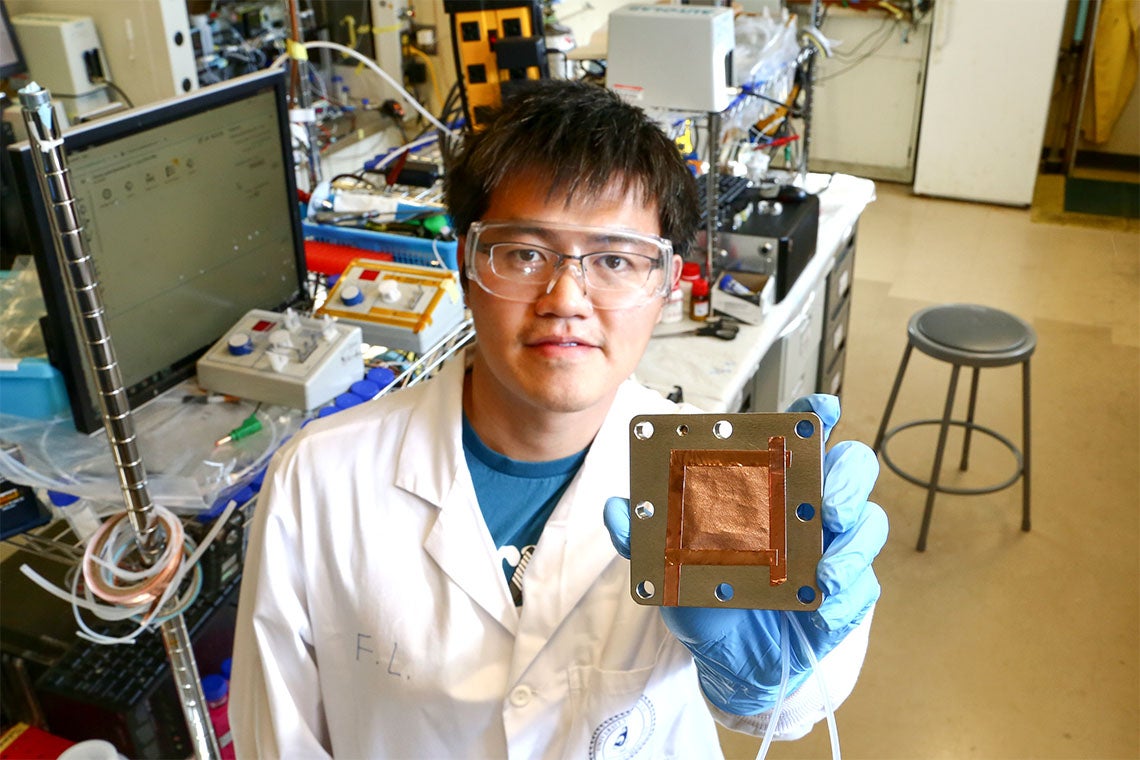

“One of the challenges with this reaction is that while some of the CO2 is converted into ethylene, most of it turns into side products, especially carbonate, which dissolves on the liquid side of the electrolyzer,” says post-doctoral researcher Fengwang Li, lead author of the new paper. “This undesired loss increases the cost of ensuing product separation and purification.”

In the latest work, Sargent’s team partnered with Caltech chemistry professors Jonas Peters and Theodor Agapie. Their published research on a class of molecules known as arylpyridiniums suggested that adding them to the catalyst could favour the production of ethylene over other side products.

Using theoretical calculations and experiments, the two teams sifted through more than a dozen kinds of arylpyridiniums before selecting one. Sure enough, adding a thin layer of this molecule to the copper catalyst surface significantly increased the selectivity of the reaction for ethylene. It also led to another benefit: lowering the working reaction pH from basic to neutral.

“The previous system required the water side of the reaction to be at high pH, very basic conditions,” says Li. “But the reaction of the CO2 with caustic soda in the water lowers the pH, so we would’ve had to continuously add chemicals to keep the pH up. The new system works just as well under neutral conditions, so we can eliminate that additional cost, as well as loss of CO2 in the form of carbonate.”

The improved catalyst also lasted longer than the previous version, remaining stable for nearly 200 hours of operation. Another enhancement – increasing the area of the catalyst surface by a factor of five – gave the teams a taste of the challenges that will need to be overcome in order to scale production to industrial levels.

While the prototype is still a long way from commercialization, the overall concept offers a promising way to address several key challenges in sustainability. It eliminates the need to extract more oil to make plastics and other consumer goods based on ethylene and it turns waste CO2 into a feedstock, adding a new incentive to invest in carbon capture.

Li points out that such a system could be powered by intermittent renewable sources, such as wind or solar power. Currently, there is often a mismatch between the amount of electricity produced by these systems and consumer demand. By storing excess electricity in the form of ethylene, the system offers a way to smooth out those peaks and valleys.

“What’s great about this CO2-to-ethylene conversion system is that you don’t need to choose between capturing and recycling CO2 emissions versus trying to prevent them from occurring in the first place by displacing the used fossil fuels,” says Li. “We can do both at the same time.”