Linguistic analysis provides insight into the vocabularies for body parts in more than a thousand languages

Human bodies have similar designs. However, languages differ in the way they divide the body into parts and name them. A team of linguists from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig and the University of Passau conducted a comparison of body part vocabularies to shed light on the interplay between language, culture, and perception of the human body. The study represents the first large-scale comparison of body part vocabularies across 1,028 language varieties and provides important insights into the variability of a universal human domain.

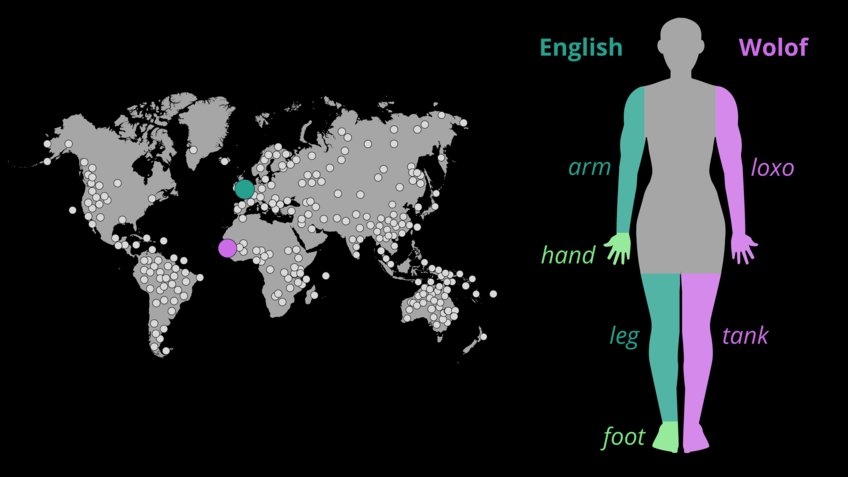

Illustration of the study’s language sample and the words for arm/hand and leg/foot in English and Wolof.

© Annika Tjuka/MPI-EVA

The study of the variation in body part vocabularies across diverse languages has attracted the attention of researchers in linguistics, anthropology, and psychology for many years. Similar to the principles developed for the semantic domain of color, universal tendencies have been identified and contrasted with culture-specific variations. The emergence of new methods in network analysis has made it possible to conduct large-scale comparisons of vocabulary in specific semantic domains to study universal and cultural structures.

In the Department of Linguistic and Cultural Evolution at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig and at the University of Passau’s Chair of Multilingual Computational Linguistics, researchers are developing databases of information about the world’s languages and computational methods for comparing these languages. For this study, they used one of these databases, , a large collection of word lists from the world’s languages, to compare the vocabulary of body parts in 1,028 languages. Using a computational approach, they extracted the words for 36 body parts in all these languages and analyzed the relationships between the words in a network analysis. “It took us several years to assemble the data in the Lexibank collection,” says Johann-Mattis List from the University of Passau, who previously worked as a senior scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, “now we can start to analyze the data in various ways.”

Languages differ in how they name body parts

“Although our bodies follow similar designs, languages differ in how they divide the body into parts and name them,” says Annika Tjuka, a postdoctoral researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, who initiated and conducted the study. “In English, we have one word for arm and another for hand, but Wolof, a language spoken in Senegal in West Africa, uses one word, loxo, to refer to both body parts. Speakers of both languages have a human body. So why do they differ in which parts are given unique names?”

The results show that a body part that is adjacent to another is more likely to have the same name. One reason for this pattern is that languages like Wolof focus on and emphasize the functional features that connect two parts. Speakers recognize that we throw a ball with our hand and arm, or that we walk with our leg and foot. Languages like English, on the other hand, focus on visual cues like the wrist or ankle to separate parts.

Body part vocabularies vary from language to language. However, general tendencies emerge within this diversity. “To understand the factors that shape linguistic diversity, we need more data. We need to document the languages spoken in linguistically diverse areas. And we need to collect data on the sociological context in which the languages are spoken,” says Tjuka.