As a scholar and teacher of literature, I have found that many people are intimidated by poetry. They find its language complex, even forbidding. They worry that they are failing to decode its symbolism. They feel that their struggle to understand a poem compromises their enjoyment of it.

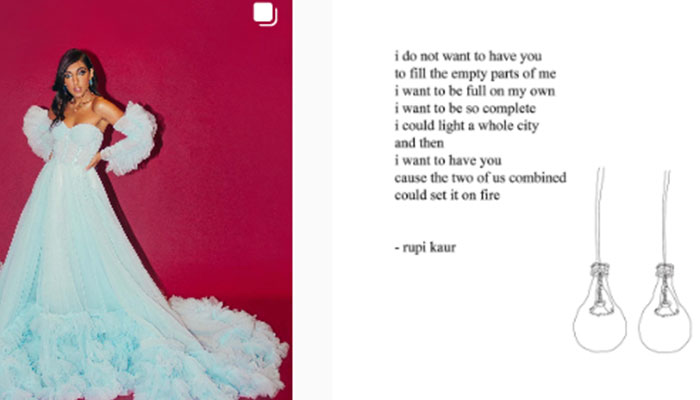

Relatable: Rupi Kaur, pictured above, is a New York Times bestselling poet, publishing three books which have been translated into 43 languages.

But students who do not immediately gravitate to Dickinson, Wordsworth or Yeats may love reading what has come to be known as Instapoetry.

As their name implies, Instapoems are written to be shared on social media. They are usually brief, fitting easily on the screen of a phone. Their language tends to be accessible and transparently emotive. And they often present themselves as visual artifacts, designed to arrest the attention of a scrolling viewer: Instapoets may (for instance) choose stylised fonts or add illustrations to their work.

A platform for diversity

Instapoetry is immensely popular. Rupi Kaur, one of the best-known writers in this genre, currently has 4.5 million followers on Instagram. Milk and Honey, a collection of her verse published in 2015, became a New York Times bestseller.

Like that of many Instapoets, Kaur’s work is polarising. To her detractors, her verses seem shallow, self-involved, and fatally unsophisticated, reducing an art form to a viral commodity. They do not rise to the level of ‘real’ poetry.

But to her fans, her work seems moving, raw, and more relevant to their own emotional lives than most of the poetry they’ve encountered in school. Instapoetry, for them, is more compelling and ‘real’ than Shakespearean sonnets or Paradise Lost.

Many fans also appreciate the fact that quite a few successful Instapoets are young women of color — from the Indian-Canadian Kaur to the Ugandan Winnie Nantongo to Lang Leav, who grew up in Sydney before moving to New Zealand. Social media, it might seem, allows these writers to bypass old-fashioned systems of academic gatekeeping.

Those who call it navel-gazing may fail to account for the ways in which poetry can transform the personal into the symbolic or universal.

But perhaps there is another way to understand the appeal of Instapoetry. Instead of defining it in opposition to more traditional verse, perhaps the two poetic modes can be mutually illuminating.

I was only vaguely familiar with Instapoetry until I came to Macquarie and began teaching a class designed by my colleague, the poet and critic Toby Davidson. Toby had assigned Milk and Honey for the first week.

As I prepared my lecture, it occurred to me that a person’s reaction to Kaur’s work sheds a great deal of light on their assumptions about poetry.

Reel life: Rupi Kaur, pictured, rose to fame on Instagram but has gone on to sell 11 million books and do live shows around the world.

What gives a poem merit? What kinds of emotional and intellectual experiences do we expect it to provide? Does one locate the value of a poem in the intentions and mindset of its creator, in its reception, in its formal qualities?

Those who scorn Instapoetry as simplistic may be too quick to conflate linguistic difficulty with artistic refinement. Those who reject it because it is packaged for popular consumption may overlook the fact that all published verse is also commodified. Those who call it navel-gazing may fail to account for the ways in which poetry can transform the personal into the symbolic or universal.

Conversely, those who celebrate Kaur for her vulnerability and openness may be missing the ways in which visceral self-expression can also unfold via cryptically evasive verse. And those who praise her as refreshingly easy to read may not realise that wrestling with dense and knotty language can also be a source of great pleasure. One can love a poem that one does not fully understand.

The accessibility and transmissibility that have fed Kaur’s online fame do not mean that her work lacks aesthetic value. But the lack of such accessibility in some non-Instagram poets does not indicate an absence of emotional authenticity.

A gateway drug

As we read Milk and Honey together, I encouraged my students to look for nuance and complexity in verses that initially seemed straightforward or transparent. At the same time, I urged them not to be put off when they encountered poems later in the term that might seem strange or obscure.

Phone friendly: Instapoems are designed to be shared on social media, writes Dr Veronica Alfano, pictured.

I was amazed by the class’s level of energy when we discussed Kaur’s writing in tutorials. Everyone had an opinion about her. Whether they loved or hated her work, then, Kaur taught my students that they were already poetry critics. If they could successfully gather textual evidence to defend their stance on Milk and Honey, they could trust that they were capable of analysing Whitman and Brontë.

And they could be inspired to read and appreciate the work of other women of color whose verse is less immediately accessible, from Gwendolyn Brooks and Audre Lord to contemporary Aboriginal Australian writers such as Alison Whittaker and Evelyn Araluen.

What is more, my students could begin to recognise continuities between Instapoetry and more canonical writing — in the apparent simplicity of Christina Rossetti’s religious poems, say, or in William Blake’s interweaving of text and image. Kaur, as one student put it, was a ‘gateway drug’ to a broader love of verse.

Instapoetry is not for everyone, nor need it be. But far from signalling the death of poetry, it can show just how rich, varied and vital this tradition still is.

is a Lecturer in the

More information: Rupi Kaur’s