At the core of the most pressing global issues of our time is a crisis of identity, where culture meets ecology.

Humanity is not seperate from nature, but a part of nature itself. Photo: Unsplash.

The importance of the environment is often downplayed as merely one in a sea of global issues. However, the environment is not only indistinguishable from these issues, it is fundamental to who we are, a UNSW environment and society expert says.

“Our social and cultural lenses shape the way we see and relate to each other and the rest of the planet,” says Associate Professor Tema Milstein from UNSW Arts & Social Sciences. “But our identities have not only social and cultural foundations and ramifications, but ecological ones as well.”

The failure of the majority of the world to acknowledge the ecological in ourselves – its denial even – has led to environmental crises, a sort of global identity crisis driving the most pressing problems of our time, from climate crisis to COVID-19.

“One of the core premises [in] western/ised cultures is that humans are not nature, that humans are not the environment, and that the environment is kind of a backdrop to humanity … the majority of societies now have reoriented their identities to be based on this separation in a way that has become very destructive,” she says.

“What we see manifest from this ‘human is separate from nature’ paradigm is societies of overconsumption, alienation and out-of-balance extraction.”

An ecocultural shift

A/Prof. Milstein says contemporary social injustices around the world are inherently entangled with these hierarchical environmental orientations. Liberator movements, from to , address related paradigms, she says.

“When we’re looking at Black Lives Matter, when we’re looking at all of the different powerful movements afoot right now, including Extinction Rebellion, School Strike 4 Climate, all the Indigenous-led protector uprisings, these are in conversation because it’s about moving away from a separate ‘power over’ way of identifying with each other – and with the planet – and into a mutual understanding of ourselves as inextricable from one another, as mutually constituted.”

‘… an ecocentric paradigm – it widens the scope, where we see humanity as part of the ecosystem …’

A/Prof. Milstein says, if we are to ensure a habitable future, today’s industrialised societies need to fundamentally redefine their relations with the planet and each other. In addition to structural and policy change, this requires individuals restoratively reconnecting with their ecological selves.

“Every identity is ecological, and if we negate this ecological dimension of ourselves, we’re able to deny our interlinkages and impacts [in relation to the environment],” she says. “But if we can reimagine who we are and how we behave as inseparable from the functioning of our ecological homes and relations, we can cultivate our way into not just habitable but thriving futures.”

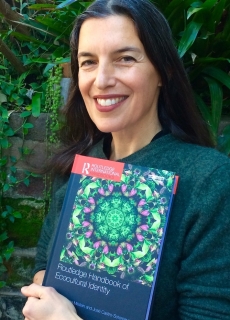

A/Prof. Tema Milstein. Photo: Supplied.

A/Prof. Milstein is co-editor of the , which brings together 40 international authors across a wide range of social sciences and humanities disciplines to introduce a framework for understanding identities as not just social and cultural, but as always ecological, as well.

The book also offers “an ecocentric paradigm – it widens the scope, where we see humanity as part of the ecosystem … it completely shifts our way of identifying from one of a removed orientation to one where we are responsive and responsible,” she says.

By considering identity as always ecocultural, the Routledge Handbook of Ecocultural Identity reframes interpersonal issues as both environmental and sociocultural issues and encourages a scalable approach to address today’s most pressing problems, she says.

“Ecocultural identity is really a very old concept, but it has largely been removed from the academy. In the Handbook, we’re conversing across disciplines about personal and societal experience around the world so we can have a common language and also engage the public sphere in this conversation.

“An ecocultural lens has the potential to affect all sorts of everyday decision-making … from individual choices to institutional choices to governmental choices, parameters will start to shift: for instance, our whole notion of what an economy is, the whole notion of quality of life.”

‘As more and more of us start to question who we are – and how who we are shapes our planet – then things will start to change rapidly.’

The Handbook’s research explores a wide range of international ecocultural identities in tension and transition, including rural and urban-dwellers, traditional and modern farmers, hunters and ranchers, counterculture makers and conservatives turned activist, miners and the urban poor, faith-based communities and children, tourists and border-dwellers, and Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities in conversation.

“It isn’t just a book that focuses on the individual, but it does bring the everyday to the fore in a way that is necessary right now,” she says. “People will find many contexts they can relate to.”

A/Prof. Milstein says she is confident an ecocultural shift is afoot and that it will only continue to build momentum.

“There is an increasing number of people focused on this right now; more people are asking really important questions, more people are taking responsibility,” she says. “As more and more of us start to question who we are – and how who we are shapes our planet – then things will start to change rapidly.”