Mondegreen is the accepted term for the words that are substituted for the actual words of a song when misunderstood by a listener. They can be amusing, bizarre or well-motivated guesswork.

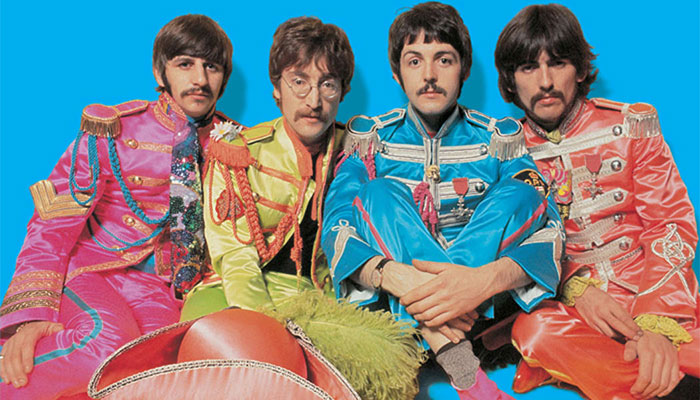

Girl with colitis: The unusual lyrics to the Beatles’ Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds gave rise to a mondegreen.

The term was coined in 1954 in a story in Harper’s Magazine. Writer Sylvia Wright had misheard the words of the centuries-old Scottish ballad, The Bonny Earl of Murray, mistaking “They have slain the Earl of Murray and laid him on the green”, for, ‘They have slain the Earl of Murray and Lady Mondegreen’. Since then, it has become a beloved part of listening to music, as everyone has their own favourite.

Amusing examples can come from children encountering words they’ve not heard before – as when a five-year-old quotes the line from the Australian national anthem as “our home is dirt by sea”. It’s hardly surprising that an Australian kid has not yet come across the word ‘girt’.

Mondegreens can also come from unusual language in the lines of popular songs, as in the Beatles’ Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds, where, “the girl with kaleidoscope eyes” is conjured up less romantically as “the girl with colitis goes by”.

Popular misunderstandings of unfamiliar words have been dramatised for comic purposes from Shakespeare on.

Even stranger is the mondegreen based on the title of Eddie Money’s song, I’ve got Two Tickets to Paradise, which comes across to some as, “I’ve got two chickens with parrot eyes”.

Mistaking the words of a popular song may of course reflect the poor quality of the recording, but in many cases the singer may simply not be articulating well. Either way, there’s plenty of scope for mondegreens between the lines in misinterpretations of the sung message.

Now in permanent use

More durable than these misunderstandings of song lyrics are the English words that have been permanently reshaped by attempts to remodel obscure elements within them – a process known as folk etymology. This happens in ordinary spoken and written language with archaic or foreign elements in half-understood words, where changes to their spelling reflects the common need to make sense of them.

Say what? The word bridegroom is a puzzling case of folk etymology.

In some cases, it interprets an obscure suffix, as in the case of penthouse (originally the French “pentice”), where house is fair enough as a remake of the second syllable. Likewise, the French word collegue, for “partner” was anglicised in the spelling colleague, to approximate the French pronunciation. The change also adds an English meaning to the second syllable, as league is a set of people with a common purpose.

Bridegroom is a more puzzling case of folk etymology, where the second element groom is a substitute for the obscure Old English word guma meaning “man”. The introduction of groom in the 16th century made some sense because of its use in contemporary pastoral poetry referring to a lusty young man, and otherwise to a male servant or attendant.

The substitution seems to have stuck, despite the now dominant connection between groom and horsemanship, making it a somewhat ill-fitting substitute for the original general word for “man”.

More complex folk etymology at work over time in the English-speaking community can be seen with the antique phrase one fell swoop. In 16th-century English, the adjective fell could express a terrible impact, and swoop then meant a single stroke of the sword, or the deadly descent of an eagle on its prey.

More figuratively, swoop could mean a coordinated attack on an unsuspecting target, as it still does in the headline ‘Police swoop on anti-vaxxers’. But as the adjective fell became obsolete, the better-known foul was substituted, which captures some of the menace of the original phrase. At the same time those who heard it could interpret it as one fowl swoop, invoking the metaphor of the eagle’s descent on its prey, as fowl is the generic word for a bird.

Tender hooks and intensive purposes

Popular misunderstandings of unfamiliar words have been dramatised for comic purposes from Shakespeare on. We now call these ‘malapropisms’, following their unforgettable use in Sheridan’s play The Rivals (1775) by Mrs Malaprop.

Aiming for effluence: Kath and Kim offered up memorable malapropisms.

Her name is based on the French phrase mal a propos, meaning ‘inappropriate’, and as applied by the playwright, it means mistaking a word for another it resembles. The resemblance is rather slight in some of Mrs Malaprop’s signature malapropisms, such as using “alligator” for allegory, though others, such as “progeny” for prodigy and “affluence” for influence, are not so far-fetched.

Pop culture continues to introduce new malapropisms, with Kath and Kim offering the memorable, “I want to be effluent, mum!” They happen by accident in real life with amusing or sometimes embarrassing consequences, as when a fashionable interior decorator is introduced as an “inferior” decorator.

Because malapropisms and mondegreens are occasional mistakes or individual misinterpretations of words and phrases, they disappear into the air waves with no lasting effects on the English language. Folk etymologies can, however, take their place in the language, especially when they help to explain obscure words. The fact that they are not strictly authentic etymologies is no barrier to them becoming established in standard English.

Eight common mondegreens

Santa Claus is Comin’ to Town

He’s makin’ a list of chicken and rice. (He’s making a list and checking it twice.)

Shake It Off, Taylor Swift

And the bakers gonna bake. (And the fakers gonna fake.)

Silent Night

Sleep in heavenly peas. (Sleep in heavenly peace.)

Bad moon rising, Creedence Clearwater Revival

There’s a bathroom on the right. (There’s a bad moon on the rise.)

Livin’ on a Prayer’, Bon Jovi

It doesn’t make a difference if we’re naked or not. (It doesn’t make a difference if we make it or not.)

Dancing Queen, ABBA

See that girl, watch her scream, kicking the dancing queen. (See that girl, watch that scene, digging the dancing queen)

We Built This City, Starship

We built this city on sausage rolls. (We built this city on rock ‘n’ roll.)

Bohemian Rhapsody, Queen

Saving his life from this warm sausage tea. (Spare him his life from this monstrosity.)

is Emeritus Professor at Macquarie University’s Department of Linguistics.