If freedom of choice is so prized in our society, should we have the right not to vote?

Critics of compulsory voting claim that it is an undemocratic infringement of a person’s liberty to be involved in politics; the case for it is that it actually enhances democracy by conferring greater legitimacy on election outcomes.

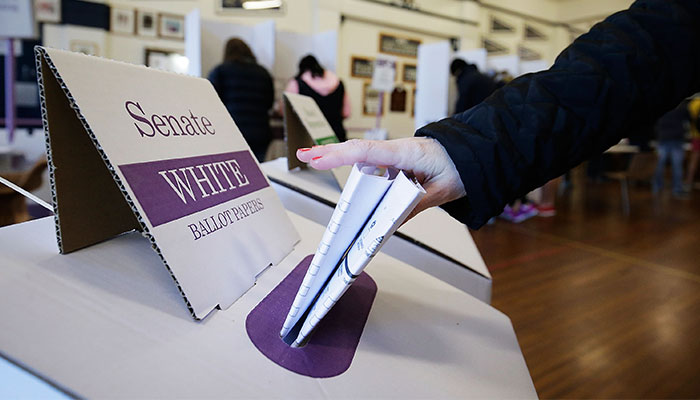

The parliamentary inquiry into the 2016 federal election called compulsory voting “a corner-stone of Australia’s democratic system”.

According to the Australian Electoral Commission, 16.4 million people were enrolled to vote in the last federal election (2019). Ninety-two per cent of them voted. Australia is the poster child for compulsory voting.

Our political order is often described as a liberal democracy. But democracy and liberalism are not the same thing. Democracy is a means of determining the majority decision. Liberalism emphasises the individual’s right to pursue their own choices and be protected from government interference.

When voter turnout falls, it tends to be those with lower incomes and less education who are less likely to vote.

While there might be a conflict between the rights of the individual and compulsory edicts, democracy and compulsion are not, strictly speaking, incompatible. In ancient Athenian democracy, for instance, there was a strong expectation that citizens would turn up to the assembly and perform their civic duties. There was little in the way of the protection of individual rights.

Some parts of the world that resist compulsory voting (the US, for example) have a very strong tradition of individual rights. Getting people out to vote is always a challenge, particularly amongst more marginalised, poorer communities. When voter turnout falls, it tends to be those with lower incomes and less education who are less likely to vote.

Looking for a level playing field

Queensland was, in 1915, the first place in Australia to introduce compulsory voting. The Liberal Government of Digby Denham was concerned that ALP shop stewards were more effective in soliciting votes and that compulsory voting would restore a level playing field (Denham lost that election).

Votes or notes: In a federal election, the penalty for first-time offenders who fail to vote is $20.

More broadly, compulsory voting was seen as a solution to a decline in voter turnout in the 1922 federal election. It was introduced federally in 1924. (Compulsory enrolment had been introduced in 1911.) It worked: in the 1925 election, voting rose from 60 per cent to more than 91 per cent.

At State level, Victoria introduced compulsory voting in 1926, NSW and Tasmania in 1928, WA in 1936, and SA in 1942.

At the time, compulsory voting was part of a pattern of policies that enforced compulsion in a range of matters. This included: compulsory enrolment to vote; compulsory vaccination; compulsory industrial arbitration; and compulsory military service.

There were two referendums on conscription during the First World War, seeking to allow the Commonwealth to send soldiers overseas for military service. They did have the right to conscript people for military service within the Commonwealth, but not to send them overseas. Both referendums were narrowly defeated.

Compulsory enrolment, voluntary voting

According to Judith Brett, author of From Secret Ballot to Democracy Sausage: How Australia got Compulsory Voting (Text, 2019), voting is compulsory in only 19 of the world’s 166 electoral democracies, and strictly enforced in nine of these, including Australia. Some countries have no compulsion whatsoever, so you don’t have to enrol and you don’t have to vote. Some have compulsory enrolment, but voluntary voting (New Zealand, for instance).

Democracy sausage: Prime Minister Scott Morrison mans the barbie.

There has been great complexity around Aboriginal voting rights, which in the 19th and 20th centuries differed across colonies and states. In Queensland and WA, Indigenous Australians had no voting rights, though there were some voting rights in other jurisdictions.

The Commonwealth Electoral Act was amended in 1962 to give all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults the right to vote in federal elections, although it wasn’t compulsory to enrol. This unusual situation remained in effect until 1984 when voting was made compulsory for all ATSI adults, in line with the rest of the nation.

Paying the price

So are Australians hell-bent on doing as they are told, or will they do anything to avoid paying a fine? Probably a bit of both! Even though we like to promote the idea of Australians being a little anti-authoritarian, we are, on the whole, people who follow rules and government advice. But no one likes to get fined, either.

In a federal election, the penalty for first time offenders is $20. If you do not vote at a State or local government election and you don’t have a valid reason, you will be fined $55.

One of the other things that compulsory voting does is dampen down the extremes. It means politicians have to listen to everyone.

The 91 per cent turnout rate in the 2016 federal election for the House of Representatives was the lowest recorded since compulsory voting in federal elections was introduced, still healthy given that turnout rates in OECD countries average 69 per cent. But voter turnout has fallen from our average of 95 per cent in each of the last three federal elections, which has prompted discussion about increasing the fines.

Advocates of compulsory voting believe it keeps the Australian political system responsive to its citizens. Parties that lack wealthy backing can contest elections without spending large sums of money on getting voters to polling booths.

Compulsory voting provides a basic level of engagement with the political process. People are forced to make a choice. And this does have an educative function, if only a minimal one: there is no mystery about voting.

The moderating factor

Compulsory voting arguably leads to a more legitimate process: people are forced to actually register a preference which means governments more accurately reflect the wants of the community, not just the most passionate, committed and enthusiastic.

One of the other things that compulsory voting does is dampen down the extremes. It means politicians have to listen to everyone, not just the noisiest groups or individuals. Compulsory voting moderates our politics.

On the other hand, critics of compulsory voting say that it not only violates the individual’s right to choose whether or not to engage with the political process, it can make political parties complacent. They don’t have to work too hard to give people a reason to turn up to vote.

Notwithstanding these objections that are periodically raised, Australians it seems, are attached to compulsory voting. From the 1940s, when polling was first conducted on the issue, there’s been a consistently strong majority opinion in its favour.

Unless there is a major change in the political culture it is likely to remain a key element in Australia’s electoral system.

is an Associate Professor in the School of Social Sciences. He teaches Politics and International Relations. His research interests are in political theory, the history of political thought and religion and politics.